Just a few months back, ESET Research published a blogpost about massive phishing campaigns across Central and Eastern Europe carried out during the second half of 2023. In those campaigns Rescoms malware (also known as Remcos), protected by AceCryptor, was delivered to potential victims with the goals of credential theft and potential gain of initial access to company networks.

Phishing campaigns targeting the region didn’t stop in 2024. In this blogpost we present what recent phishing campaigns looked like and how the choice of delivery mechanism shifted away from AceCryptor to ModiLoader.

Key points of this blogpost:

- ESET detected nine notable ModiLoader phishing campaigns during May 2024 in Poland, Romania, and Italy.

- These campaigns targeted small and medium-sized businesses.

- Seven of the campaigns targeted Poland, where ESET products protected over 21,000 users.

- Attackers deployed three malware families via ModiLoader: Rescoms, Agent Tesla, and Formbook.

- Attackers used previously compromised email accounts and company servers, not only to spread malicious emails but also to host malware and collect stolen data.

Overview

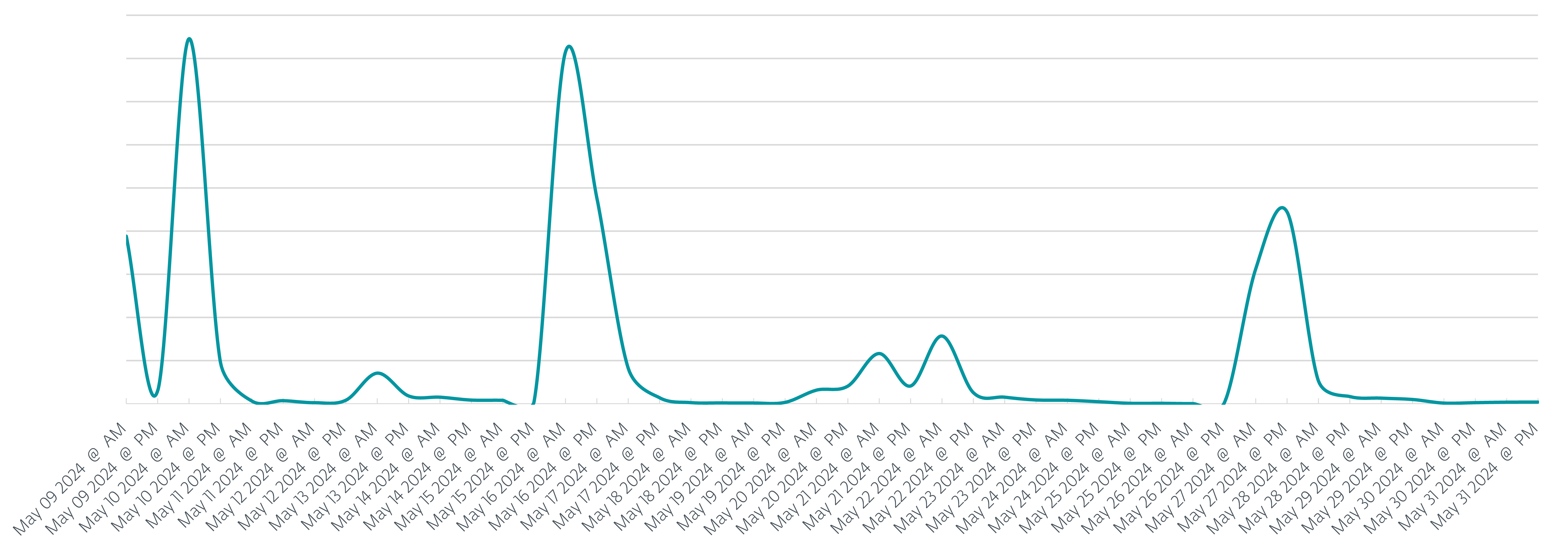

Even though the phishing campaigns have been ongoing throughout the first half of 2024, this blogpost focuses just on May 2024, as this was an eventful month. During this period, ESET products protected over 26,000 users, over 21,000 (80%) of whom were in Poland. In addition to Poland, where over 80% of potential victims were located, Italy and Romania were also targeted by the phishing campaigns. In total we registered nine phishing campaigns, seven of which targeted Poland throughout May, as can be seen in Figure 1.

In comparison with the campaigns that took place during the end of 2023, we see a shift away from using AceCryptor as a tool of choice to protect and successfully deliver the malware. Instead, in all nine campaigns, attackers used ModiLoader (aka DBatLoader) as the preferred delivery tool of choice. The final payload to be delivered and launched on the compromised machines varied; we’ve detected campaigns delivering:

- Formbook – information stealing malware discovered in 2016,

- Agent Tesla – a remote access trojan and information stealer, and

- Rescoms RAT – remote control and surveillance software, able to steal sensitive information.

Campaigns

In general, all campaigns followed a similar scenario. The targeted company received an email message with a business offer that could be as simple as “Please provide your best price offer for the attached order no. 2405073”, as can be seen in Figure 2.

In other campaigns, email messages were more verbose, such as the phishing email in Figure 3, which can be translated as follows:

Hi,

We are looking to purchase your product for our client.

Please find the attached inquiry for the first step of this purchase.

The attached sheet contains target prices for most products. I highlighted 10 elements to focus on pricing – the rest of the items are optional to price (we will apply similar price level based on other prices).

Please get back to me before 28/05/2024

If you need more time, please let me know how much you will need.

If you have any questions, please also let me know.

As in the phishing campaigns of H2 2023, attackers impersonated existing companies and their employees as the technique of choice to increase campaign success rate. In this way, even if the potential victim looked for the usual red flags (aside from potential translation mistakes), they were just not there, and the email looked as legitimate as it could have.

Inside the attachments

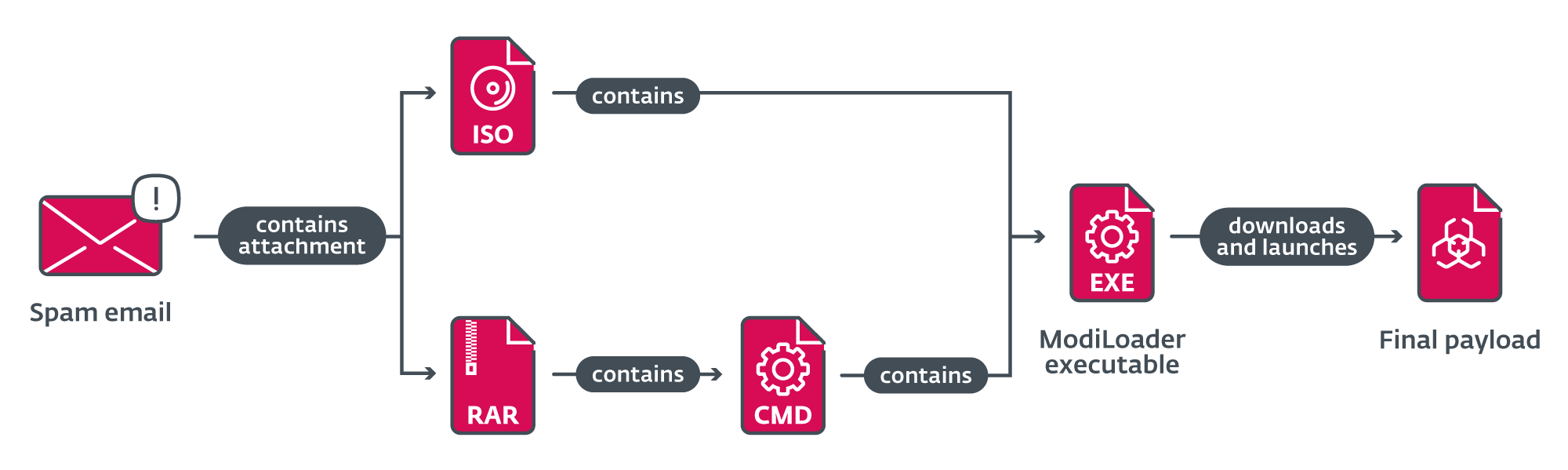

Emails from all campaigns contained a malicious attachment that the potential victim was incentivized to open, based on the text of the email. These attachments had names like RFQ8219000045320004.tar (as in Request for Quotation) or ZAMÓWIENIE_NR.2405073.IMG (translation: ORDER_NO) and the file itself was either an ISO file or archive.

In campaigns where an ISO file was sent as an attachment, the content was the ModiLoader executable (named similarly or the same as the ISO file itself) that would be launched if a victim tried to open the executable.

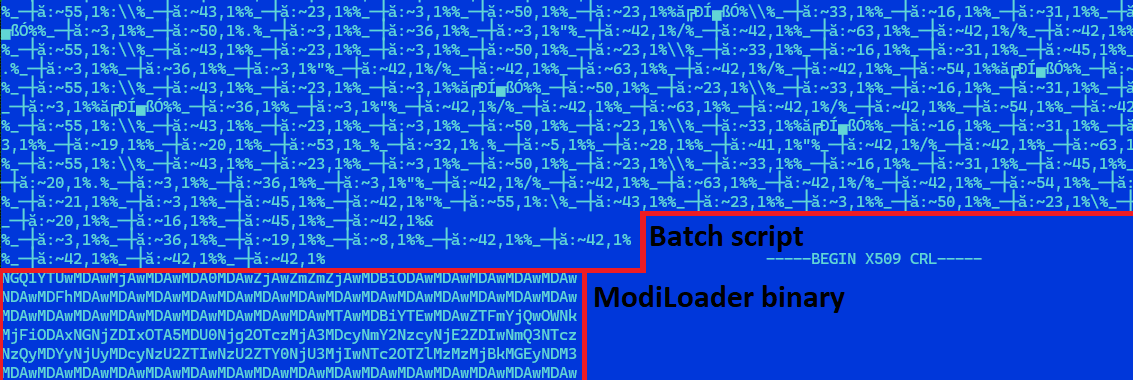

In the other case, when a RAR archive was sent as an attachment, the content was a heavily obfuscated batch script, with the same name as the archive and with the .cmd file extension. This file also contained a base64-encoded ModiLoader executable, disguised as a PEM-encoded certificate revocation list. The script is responsible for decoding and launching the embedded ModiLoader (Figure 4).

When ModiLoader is launched

ModiLoader is a Delphi downloader with a simple task – to download and launch malware. In two of the campaigns, ModiLoader samples were configured to download the next-stage malware from a compromised server belonging to a Hungarian company. In the rest of the campaigns ModiLoader downloaded the next stage from Microsoft’s OneDrive cloud storage. We observed four accounts where second-stage malware was hosted. The whole chain of compromise from receiving the malicious email until launching the final payload is summarized in Figure 5.

Data exfiltration

Three different malware families were used as a final payload: Agent Tesla, Rescoms, and Formbook. All these families are capable of information stealing and thus allow attackers not only to expand their datasets of stolen information, but also to prepare the ground for their next campaigns. Even though the exfiltration mechanisms differ between malware families and campaigns, it is worth mentioning two examples of these mechanisms.

In one campaign, information was exfiltrated via SMTP to an address using a domain similar to that of a German company. Note that typosquatting was a popular technique used in the Rescoms campaigns from the end of last year. These older campaigns used typosquatted domains for sending phishing emails. One of the new campaigns used a typosquatted domain for exfiltrating data. When someone tried to visit web pages of this typosquatted domain, they’d be immediately redirected to the web page of the legitimate (impersonated) company.

In another campaign, we saw data being exfiltrated to a web server of a guest house located in Romania (a country targeted now and in the past by such campaigns). In this case, the web server seems legitimate (so no typosquatting) and we believe that the accommodation’s server had been compromised during previous campaigns and abused for malicious activities.

Conclusion

Phishing campaigns targeting small and medium-sized businesses in Central and Eastern Europe are still going strong in the first half of 2024. Furthermore, attackers take advantage of previously successful attacks and actively use compromised accounts or machines to further spread malware or collect stolen information. In May alone, ESET detected nine ModiLoader phishing campaigns, and even more outside this time frame. Unlike the second half of 2023, when Rescoms packed by AceCryptor was the preferred malware of choice of the attackers, they didn’t hesitate to change the malware they use to be more successful. As we presented, there are multiple other malware families like ModiLoader or Agent Tesla in the arsenal of these attackers, ready to be used.

For any inquiries about our research published on WeLiveSecurity, please contact us at threatintel@eset.com.ESET Research offers private APT intelligence reports and data feeds. For any inquiries about this service, visit the ESET Threat Intelligence page.

IoCs

A comprehensive list of indicators of compromise (IoCs) can be found in our GitHub repository.

Files

|

SHA-1 |

Filename |

Detection |

Description |

|

E7065EF6D0CF45443DEF |

doc023561361500.img |

Win32/TrojanDownloader. |

Malicious attachment from phishing campaign carried out in Poland during May 2024. |

|

31672B52259B4D514E68 |

doc023561361500__ |

Win32/TrojanDownloader. |

ModiLoader executable from phishing campaign carried out in Poland during May 2024. |

|

B71070F9ADB17C942CB6 |

N/A |

MSIL/Spy.Agent.CVT |

Agent Tesla executable from phishing campaign carried out in Poland during May 2024. |

|

D7561594C7478C4FE37C |

ZAMÓWIENIE_NR.2405073. |

Win32/TrojanDownloader. |

Malicious attachment from phishing campaign carried out in Poland during May 2024. |

|

47AF4CFC9B250AC4AE8C |

ZAMÓWIENIE_NR.2405073. |

Win32/TrojanDownloader. |

ModiLoader executable from phishing campaign carried out in Poland during May 2024. |

|

2963AF32AB4D497CB41F |

N/A |

Win32/Formbook.AA |

Formbook executable from phishing campaign carried out in Poland during May 2024. |

|

5DAB001A2025AA91D278 |

RFQ8219000045320004. |

Win32/TrojanDownloader. |

Malicious attachment from phishing campaign carried out in Poland during May 2024. |

|

D88B10E4FD487BFCCA6A |

RFQ8219000045320004. |

Win32/TrojanDownloader. |

Malicious batch script from phishing campaign carried out in Poland during May 2024. |

|

F0295F2E46CEBFFAF789 |

N/A |

Win32/TrojanDownloader. |

ModiLoader executable from phishing campaign carried out in Poland during May 2024. |

|

3C0A0EC8FE9EB3E5DAB2 |

N/A |

Win32/Rescoms.B |

Rescoms executable from phishing campaign carried out in Poland during May 2024. |

|

9B5AF677E565FFD4B15D |

DOCUMENT_BT24PDF.IMG |

Win32/TrojanDownloader. |

Malicious attachment from phishing campaign carried out in Romania during May 2024. |

|

738CFBE52CFF57098818 |

DOCUMENT_BT24PDF.exe |

Win32/TrojanDownloader. |

ModiLoader executable from phishing campaign carried out in Romania during May 2024. |

|

843CE8848BCEEEF16D07 |

N/A |

Win32/Formbook.AA |

Formbook executable from phishing campaign carried out in Romania during May 2024. |

MITRE ATT&CK techniques

This table was built using version 15 of the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

|

Tactic |

ID |

Name |

Description |

|

Reconnaissance |

Gather Victim Identity Information: Email Addresses |

Email addresses and contact information (either bought or gathered from publicly available sources) were used in phishing campaigns to target companies across multiple countries. |

|

|

Resource Development |

Compromise Accounts: Email Accounts |

Attackers used compromised email accounts to send malicious emails in phishing campaigns to increase their phishing email’s credibility. |

|

|

Obtain Capabilities: Malware |

Attackers bought licenses and used multiple malware families for phishing campaigns. |

||

|

Acquire Infrastructure: Web Services |

Attackers used Microsoft OneDrive to host malware. |

||

|

Compromise Infrastructure: Server |

Attackers used previously compromised servers to host malware and store stolen information. |

||

|

Initial Access |

Phishing |

Attackers used phishing messages with malicious attachments to compromise computers and steal information from companies in multiple European countries. |

|

|

Phishing: Spearphishing Attachment |

Attackers used spearphishing messages to compromise computers and steal information from companies in multiple European countries. |

||

|

Execution |

User Execution: Malicious File |

Attackers relied on users opening archives containing malware and launching a ModiLoader executable. |

|

|

Credential Access |

Credentials from Password Stores: Credentials from Web Browsers |

Attackers tried to steal credential information from browsers and email clients. |