Much like the life and mysterious demise of Pharaoh Tutankhamun, also known as King Tut, the threat landscape in Latin America (LATAM) remains shrouded in mystery. This is primarily due to the limited global attention on the evolving malicious campaigns within the region. While notable events like ATM attacks, the banking trojans born in Brazil, and the Machete cyberespionage operations have garnered media coverage, we are aware that there is more to the story.

In a parallel to how archaeological excavations of King Tut’s tomb shed light on ancient Egyptian life, we embarked on a journey to delve into less-publicized cyberthreats affecting Latin American countries. Our initiative, named Operation King TUT (The Universe of Threats), sought to explore this significant threat landscape. On October 5th, we presented the results of our comparative analysis at the Virus Bulletin 2023 conference: the full conference paper can be read here.

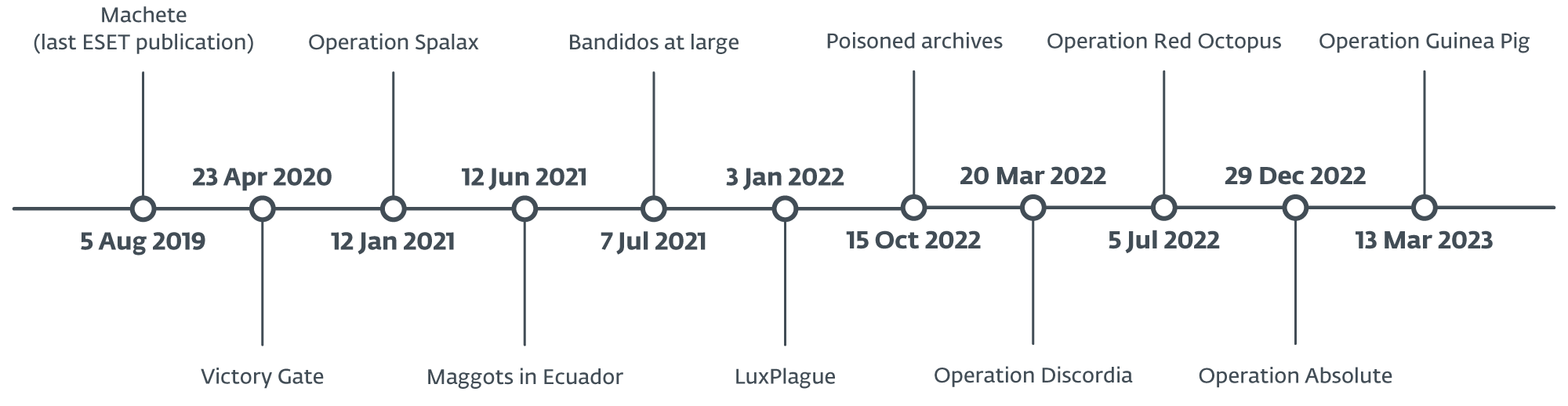

In the analysis, we chose to look back at various publicly documented campaigns targeting the LATAM region between 2019 and 2023, as can be seen in the timeline below. All of these cybercriminal activities are detected exclusively in Latin America and are not associated with global crimeware. Since each of these operations has its own unique traits and doesn’t appear linked to any known threat actor, it’s highly likely that multiple actors are at play.

Our research revealed a notable shift from simplistic, opportunistic crimeware to more complex threats. Notably, we have observed a transition in targeting, moving from a focus on the general public to high-profile users, including businesses and governmental entities. These threat actors continually update their tools, introducing different evasion techniques to increase the success of their campaigns. Furthermore, they have expanded their crimeware business beyond Latin America, mirroring the pattern seen in banking trojans born in Brazil.

Our comparison also shows that the majority of malicious campaigns seen in the region are directed at enterprise users, including government sectors, by employing primarily spearphishing emails to reach potential victims, often masquerading as recognized organizations within specific countries in the region, particularly government or tax entities.

The precision and specificity observed in these attacks point to a high level of targeting, indicating that the threat actors have detailed knowledge about their intended victims. In these campaigns, attackers utilize malicious components like downloaders and droppers, mostly created in PowerShell and VBS.

Regarding the tools used in these malicious operations in Latin America, our observations indicate a preference for RATs, particularly from the njRAT and AsyncRAT families. Additionally, in campaigns primarily targeting government entities, we have identified the use of other malware families like Bandook and Remcos, albeit to a lesser extent.

Based on the conclusions resulting from our comparison, we believe that there is more than just one group behind the proliferation of these types of campaigns and that these groups are actively looking into different techniques and ways for their campaigns to be as successful as possible. Additionally, we suspect that socioeconomic disparities prevalent in Latin America may influence the modus operandi of attackers in this region, although this particular aspect falls beyond the scope of our research. The full VB2023 conference paper about Operation King TUT is available here.

Aggregated indicators of compromise (IoCs) are available on our GitHub repository.

For any inquiries about our research published on WeLiveSecurity, please contact us at threatintel@eset.com.

ESET Research offers private APT intelligence reports and data feeds. For any inquiries about this service, visit the ESET Threat Intelligence page.