As the COVID-19 pandemic spread around the globe, many of us, myself included, turned to working full-time from home. Many of ESET’s employees were already accustomed to working remotely part of the time, and it was largely a matter of scaling up existing resources to handle the influx of new remote workers, such as purchasing a few more laptops and VPN licenses.

The same, though, could not be said for many organizations around the world, who either had to set up access for their remote workforce from scratch or at least significantly scale up their Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) servers to make remote access usable for many concurrent users.

To help those IT departments, particularly the ones for whom a remote workforce was something new, I worked with our content department to create a paper discussing the types of attacks ESET was seeing that were specifically targeting RDP, and some basic steps to secure against them. That paper can be found here on ESET's corporate blog, in case you are curious.

About the same time this change was occurring, ESET re-introduced our global threat reports, and one of the things we noted was RDP attacks continued to grow. According to our threat report for the first four months of 2022, over 100 billion such attacks were attempted, over half of which were traced back to Russian IP address blocks.

Clearly, there was a need to take another look at the RDP exploits that were developed, and the attacks they made possible, over the past couple of years to report what ESET was seeing through its threat intelligence and telemetry. So, we have done just that: a new version of our 2020 paper, now titled Remote Desktop Protocol: Configuring remote access for a secure workforce, has been published to share that information.

What’s been happening with RDP?

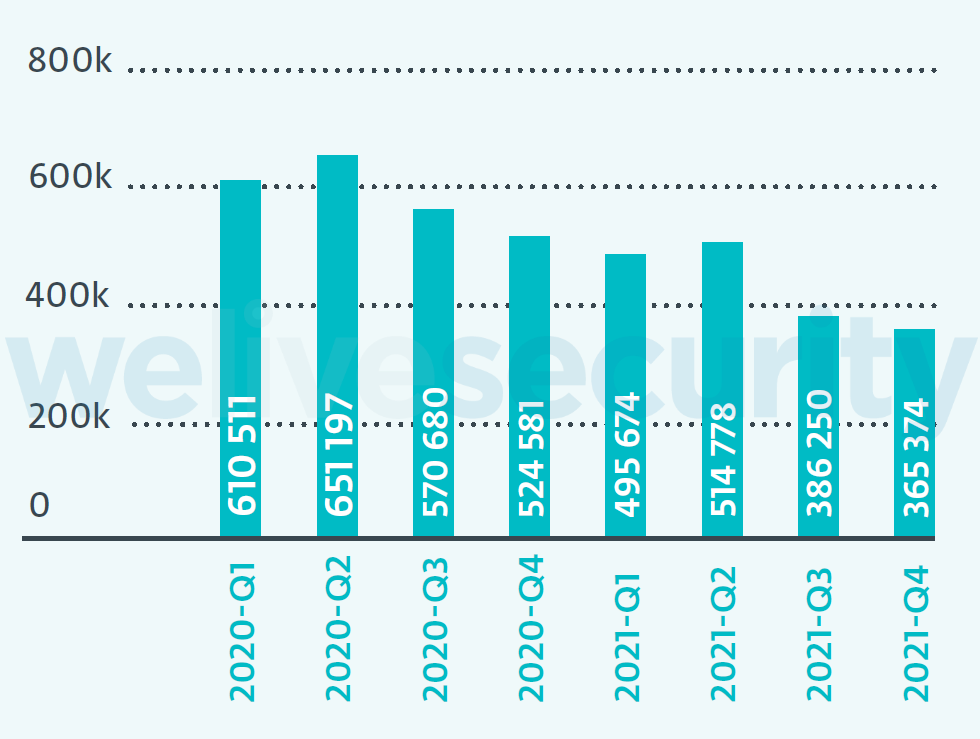

In the first part of this revised paper, we look at how attacks have evolved over the past couple of years. One thing I would like to share is that not every attack has been on the increase. For one type of vulnerability, ESET saw a marked decrease in exploitation attempts:

- Detections of the BlueKeep (CVE-2019-0708) wormable exploit in Remote Desktop Services have decreased 44% from their peak in 2020. We attribute this decrease to a combination of patching practices for affected versions of Windows plus exploit protection at the network perimeter.

Figure 1. CVE-2019-0708 “BlueKeep” detections worldwide (source: ESET telemetry)

One of the oft-heard complaints about computer security companies is that they spend too much time talking about how security is always getting worse and not improving, and that any good news is infrequent and transitory. Some of that criticism is valid, but security is always an ongoing process: new threats are always emerging. In this instance, seeing attempts to exploit a vulnerability like BlueKeep decrease over time seems like good news. RDP remains widely used, and this means that attackers are going to continue conducting research into vulnerabilities that they can exploit.

For a class of exploits to disappear, whatever is vulnerable to them has to stop being used. The last time I remember seeing such a widespread change was when Microsoft released Windows 7 in 2009. Windows 7 came with support for AutoRun (AUTORUN.INF) disabled. Microsoft then backported this change to all previous versions of Windows, although not perfectly the first time. A feature since Windows 95 was released in 1995, AutoRun was heavily abused to propagate worms like Conficker. At one point, AUTORUN.INF-based worms accounted for nearly a quarter of threats encountered by ESET’s software. Today, they account for under a tenth of a percent of detections.

Unlike AutoPlay, RDP remains a regularly used feature of Windows and just because there is a decrease in the use of a single exploit against it that does not mean that attacks against it as a whole are on the decrease. As a matter of fact, attacks against its vulnerabilities have increased massively, which brings up another possibility for the decrease in BlueKeep detections: Other RDP exploits might be so much more effective that attackers have switched over to them.

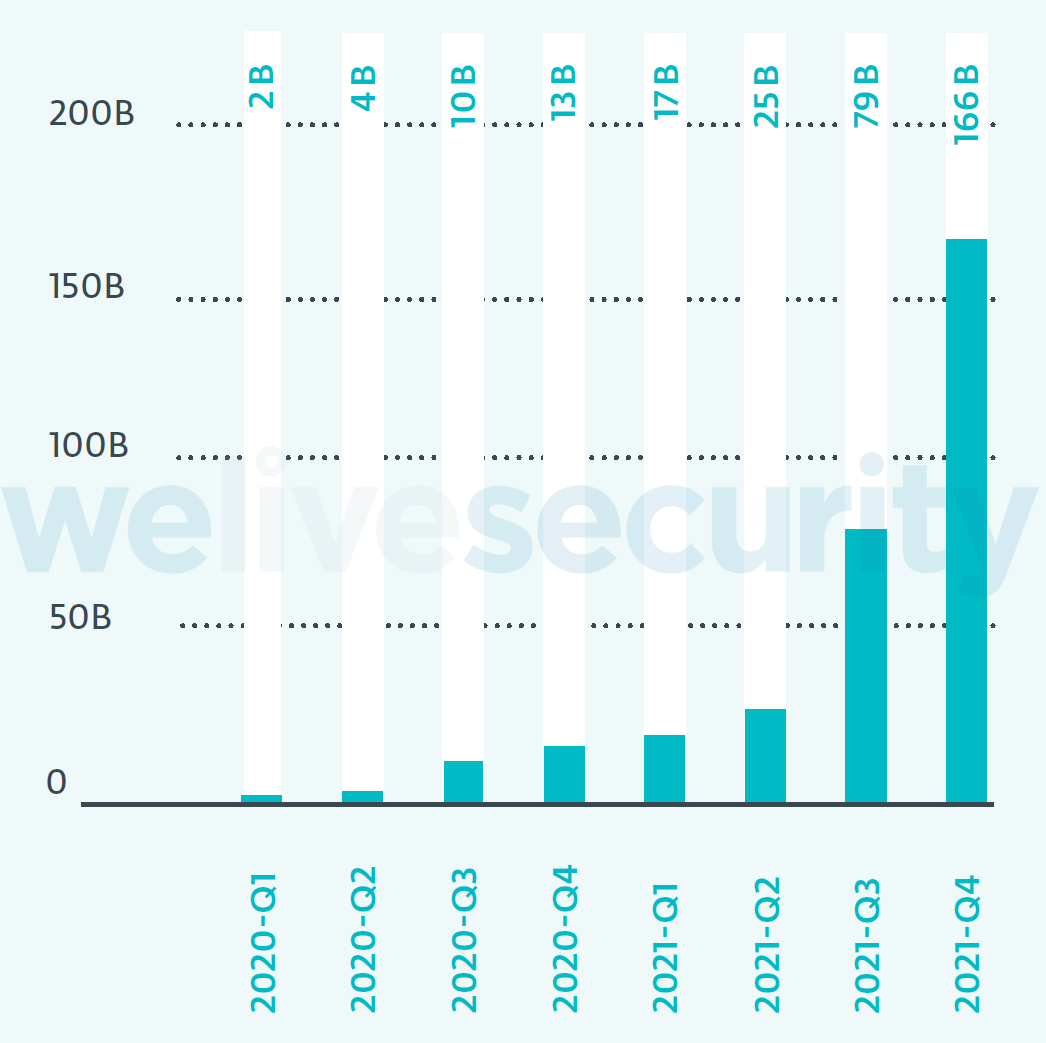

Looking at two years’ worth of data from the beginning of 2020 to the end of 2021 would seem to agree with this assessment. During that period, ESET telemetry shows a massive increase in malicious RDP connection attempts. Just how large was the jump? In the first quarter of 2020, we saw 1.97 billion connection attempts. By the fourth quarter of 2021, that had jumped to 166.37 billion connection attempts, an increase of over 8,400%!

Figure 2. Malicious RDP connection attempts detected worldwide (source: ESET telemetry). Absolute numbers are rounded

Clearly, attackers are finding value in connecting to organizations’ computers, whether for conducting espionage, planting ransomware, or some other criminal act. But it is also possible to defend against these attacks.

The second part of the revised paper provides updated guidance on defending against attacks on RDP. While this advice is more geared at those IT professionals who may be unaccustomed to hardening their network, it contains information that may even be helpful to more experienced staff.

New data on SMB attacks

With the set of data on RDP attacks came an unexpected addition of telemetry from attempted Server Message Block (SMB) attacks. Given this added bonus, I could not help but look at the data, and felt it was complete and interesting enough that a new section on SMB attacks, and defenses against them, could be added to the paper.

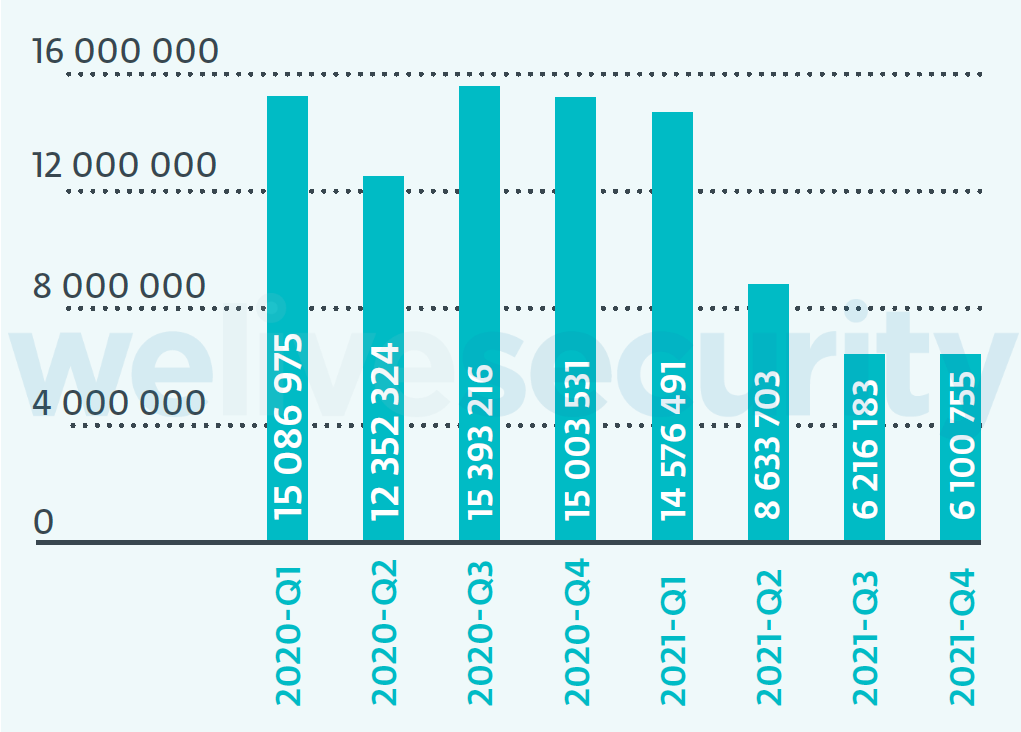

SMB can be thought of as a companion protocol to RDP, in that it allows files, printers, and other network resources to be accessed remotely during an RDP session. 2017 saw the public release of the EternalBlue (CVE-2017-0144) wormable exploit. Use of the exploit continued to grow through 2018, 2019, and into 2020, according to ESET telemetry.

Figure 3. CVE -2017-0144 “EternalBlue” detections worldwide (Source: ESET telemetry)

The vulnerability exploited by EternalBlue is present only in SMBv1, a version of the protocol dating back to the 1990s. However, SMBv1 was widely implemented in operating systems and networked devices for decades and it was not until 2017 that Microsoft began shipping versions of Windows with SMBv1 disabled by default.

At the end of 2020 and through 2021, ESET saw a marked decrease in attempts to exploit the EternalBlue vulnerability. As with BlueKeep, ESET attributes this reduction in detections to patching practices, improved protections at the network perimeter, and decreased usage of SMBv1.

Final thoughts

It is important to note that this information presented in this revised paper was gathered from ESET’s telemetry. Any time one is working with threat telemetry data, there are certain provisos that must be applied to interpreting it:

- Sharing threat telemetry with ESET is optional; if a customer does not connect to ESET’s LiveGrid® system or share anonymized statistical data with ESET, then we will not have any data on what their installation of ESET’s software encountered.

- The detection of malicious RDP and SMB activity is done through several layers of ESET’s protective technologies, including Botnet Protection, Brute Force Attack Protection, Network Attack Protection, and so forth. Not all of ESET’s programs have these layers of protection. For example, ESET NOD32 Antivirus provides a basic level of protection against malware for home users and does not have these protective layers. They are present in ESET Internet Security and ESET Smart Security Premium, as well as in ESET’s endpoint protection programs for business users.

- Although it was not used in the preparation of this paper, ESET threat reports provide geographic data down to the region or country level. GeoIP detection is mixture of science and art, and factors such as the use of VPNs and the rapidly changing ownership of IPv4 blocks can have an impact on location accuracy.

- Likewise, ESET is one of the many defenders in this space. Telemetry tells us what installations of ESET’s software are preventing, but ESET has no insight into what customers of other security products are encountering.

Because of these factors, the absolute number of attacks is going to be higher than what we can learn from ESET’s telemetry. That said, we believe that our telemetry is an accurate representation of the overall situation; the overall increase and decrease in detections of various attacks, percentage-wise, as well as the attack trends noted by ESET, are likely to be similar across the security industry.

Special thanks to my colleagues Bruce P. Burrell, Jakub Filip, Tomáš Foltýn, Rene Holt, Előd Kironský, Ondrej Kubovič, Gabrielle Ladouceur-Despins, Zuzana Pardubská, Linda Skrúcaná, and Peter Stančík for their assistance in the revision of this paper.

Aryeh Goretsky, ZCSE, rMVP

Distinguished Researcher, ESET