I have been fascinated with the thought of being able to break into a bank ever since my love for bank robbery films began in the 1990s, and I think I may have finally uncovered a way to do it – well, sort of. The security of typical banking apps impresses me immensely, and with my security hat on I have not yet thought of a way to bypass the usually robust in-built measures designed to protect the money of banks’ customers, which is entirely the way it should be. However, if banks are so secure, I wondered if there may be a way of attacking one of the most popular third parties that often already have complete access to people’s funds – PayPal.

To put things into perspective, over the last 18 months I have successfully shown how easy it is to hijack a WhatsApp or Snapchat account without the right security set on the accounts. This left me wondering whether I should up the ante and attempt to gain control of a financial account using similar tactics. Turns out, with just the simple art of “shoulder surfing”, your PayPal account could indeed be compromised and you could lose thousands of dollars.

Social engineering attacks are increasingly common and rising in popularity among criminal gangs. On the other hand, they are difficult to properly experiment with on someone under test conditions simply because the “victims” are aware of the proposed attack vector and this immediately throws the trial out of the window without proving its viability. However, I have found a way to take ownership of someone’s PayPal account and prove it in a legitimate and legal experiment; even more importantly, you’ll also learn how to avoid this attack on your account.

In order to demonstrate this latest proof of concept, I didn’t choose to target just anyone – I wanted to fully test my hypothesis on someone who would be very likely to spot what was going on, especially when money was involved. Which is why I chose to target a friend (let’s call him Dave) who’s been in the security industry for well over 20 years. In fact, Dave is a guru when it comes to computer security and very few scams pass his eyes without him realizing what’s going on. Perfect.

Let the experiment begin

I recently arranged to meet up with Dave and a few more friends who I had only seen a handful of times in the last 18 months. I asked Dave if he would agree to play a pivotal role in a little hack. In the name of cybersecurity awareness and improving fraud prevention, he agreed to allow me to try anything on his account as long as I bought lunch – he didn’t specify whose bank account to use, though!

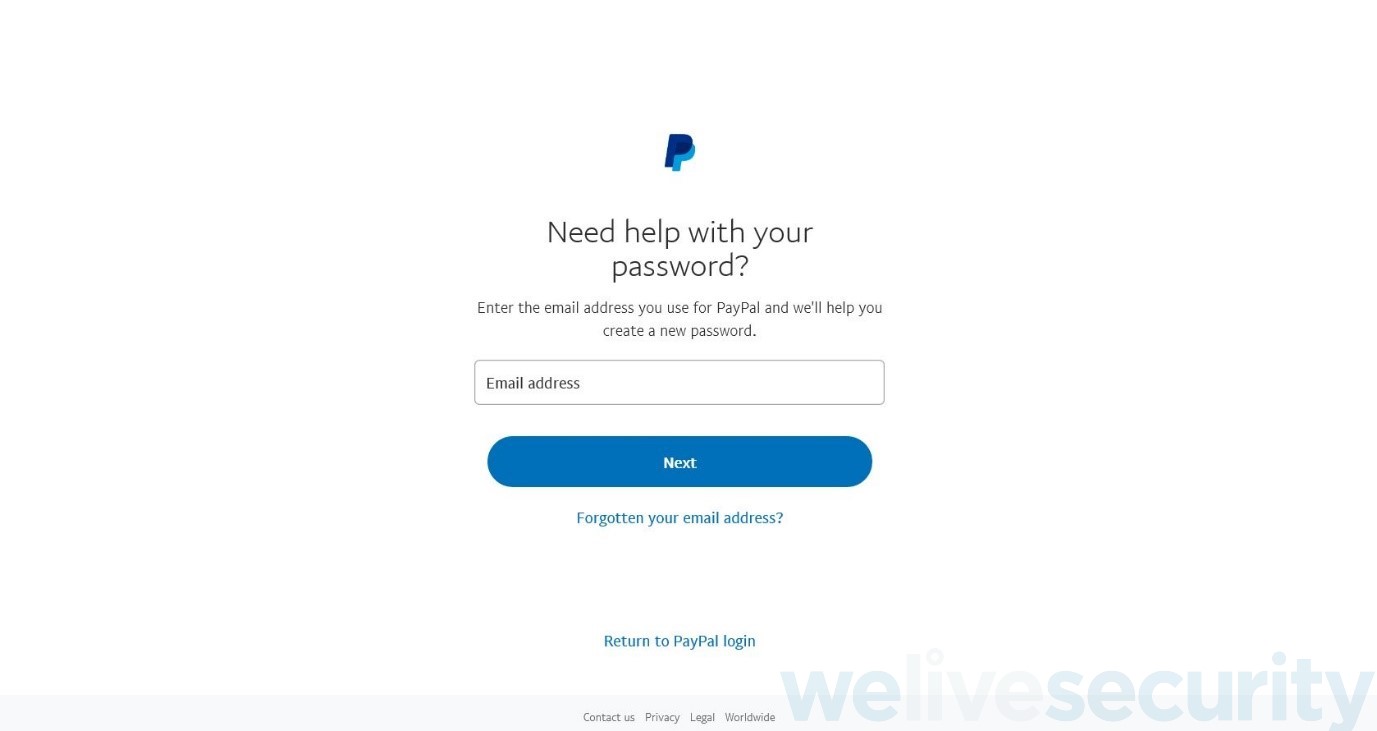

While in a restaurant, Dave placed his phone down on the table and was chatting to a few of us around the table. I brought my laptop with me and so in the meantime, I opened the PayPal website and went straight to a hacker’s favorite section: the forgotten password page.

I know Dave’s personal email address and I guessed he also uses it for PayPal, too. In a genuine attack, the hacker would need to know the target’s email address but these days, many people’s email addresses can be found via a few searches. Google, LinkedIn, even Instagram may show your email address, which is all that is needed to initiate this attack on any PayPal user.

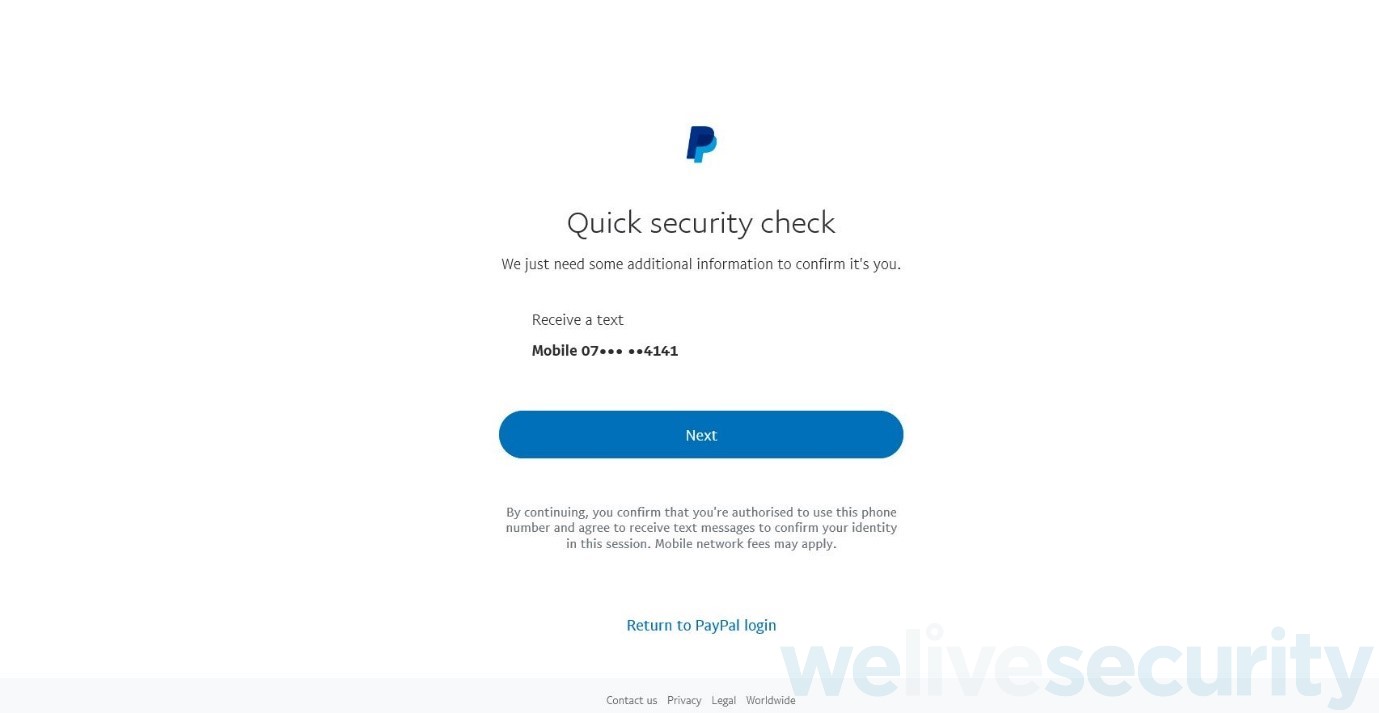

PayPal then requests to send a “quick security check” via a variety of means. In my research, this could be via a text, an email, a phone call, an authenticator app, even a WhatsApp! Some people even have the option to check security via security questions, which are no doubt as old as the account. And if, as mine did, these might include answers that are extremely easy to find out. I had no idea I still had these as an option and in no settings could I find where to eliminate some forms of security check. Back with Dave and the only security check he had on offer was via a text, which is the one of interest for now.

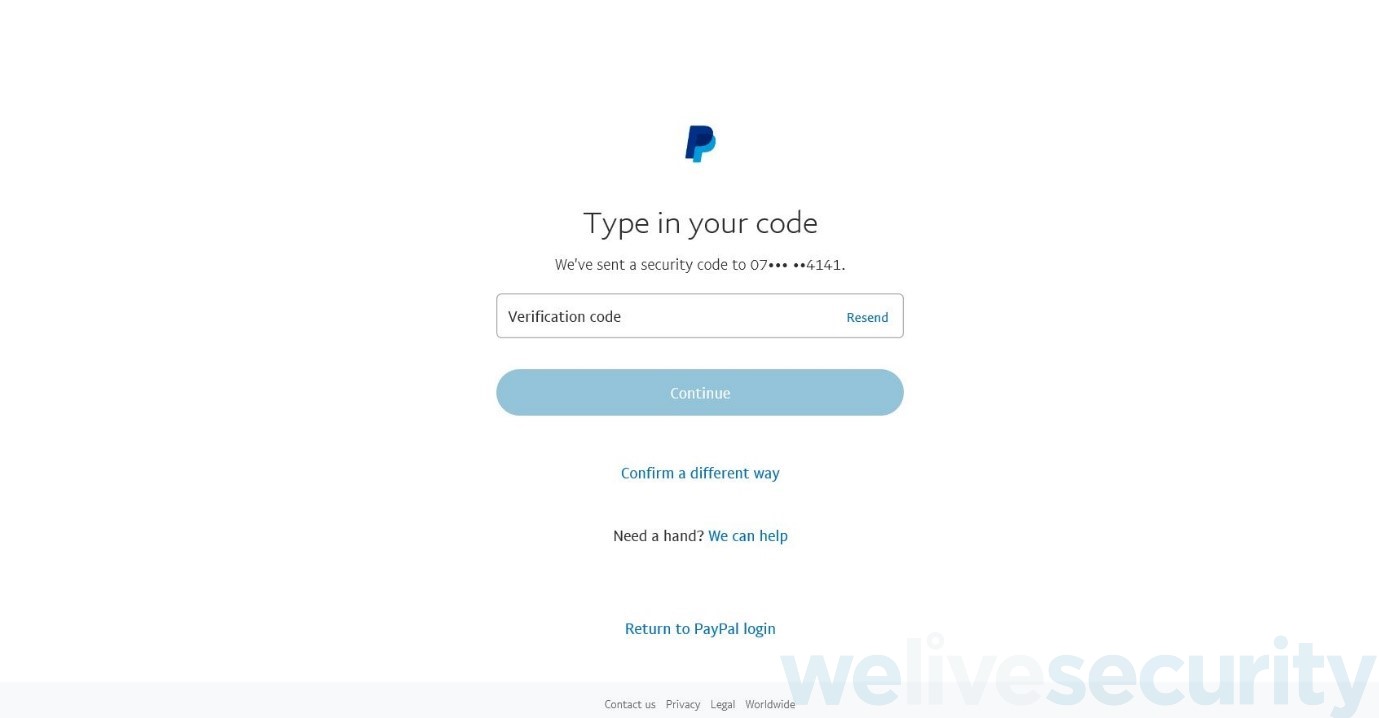

With Dave still talking to colleagues in the meeting room, I clicked “Next”, which sent a six-digit code to his phone immediately.

I leant over to Dave’s phone and without him noticing, I tapped the screen to wake it up. As he had not disabled message previews on his phone’s lock screen, I easily viewed the code and typed it into the verification code field on the website. This was all I needed, and I was now in his account! PayPal’s website then asked me to choose a new password for his account and I changed it to one my password generator had just created.

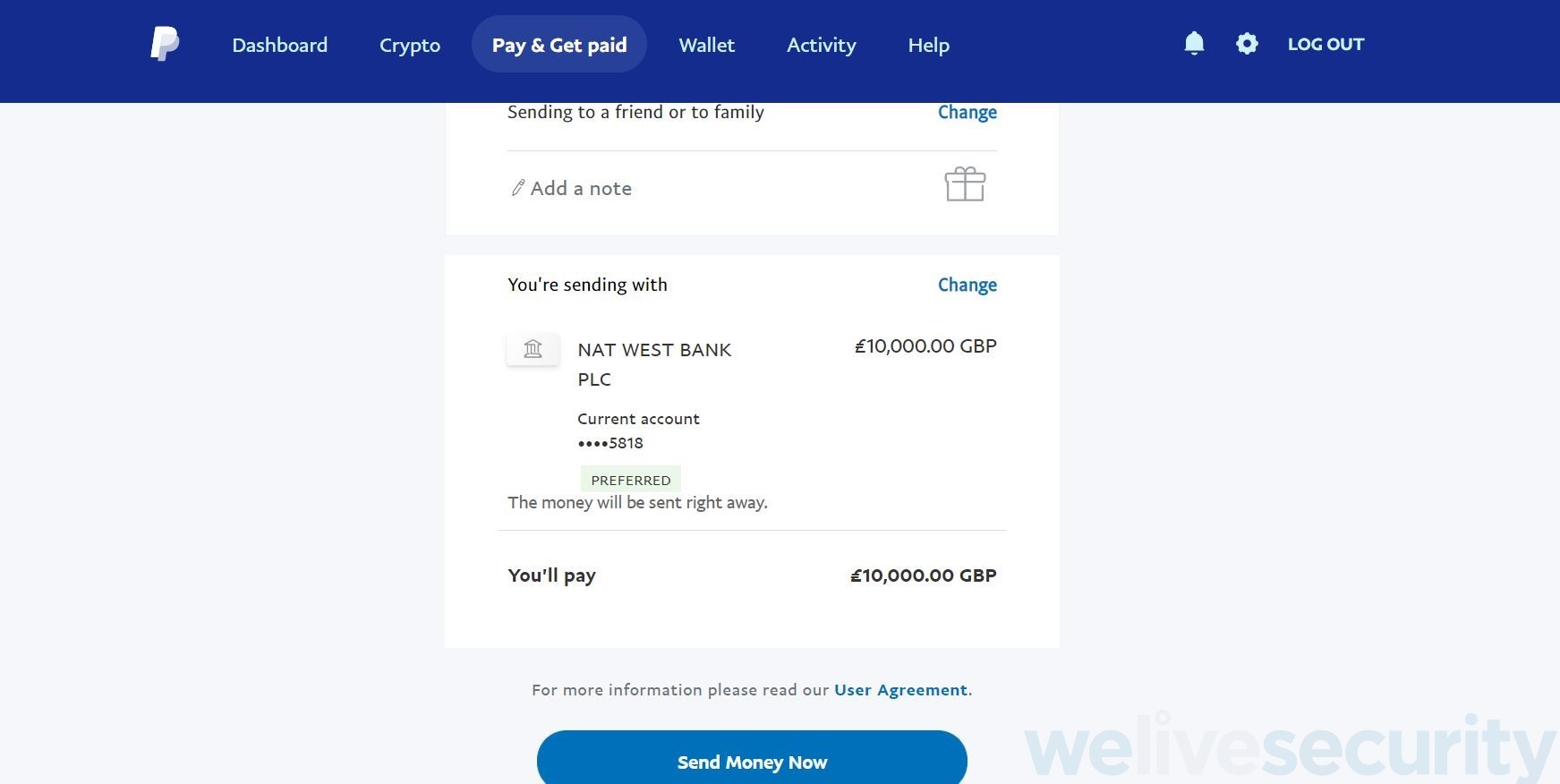

So there I was, staring at Dave’s PayPal dashboard and all the cards associated with his account. I genuinely felt like I had broken into a bank! I was looking at all the options and his linked bank cards. I could have easily linked a bank or credit card or even looked at his personal details such as his home address. I could have changed the email address for his account, his address or name, but to really test this attack I clicked on “send money”. Although I could have sent up to £10,000 (I was tempted and even typed it in for effect), I chose to send only £10 to my own PayPal account – remember he had authorized this and I had promised to reimburse him for any money that was moved!

The moment I clicked “send money now”, Dave’s phone received an email confirming the money had just moved from his account and this is where he stopped in his tracks when he read it on his Apple Watch. But I was home and dry. I had moved the money and asked him if I could buy him lunch. His face indicated that he was not impressed.

So, to recap, at this point, I could have sent £10,000 to any of the world’s 300 million PayPal accounts from just seeing a code on someone’s phone. This doesn’t make sense to me and people clearly need to be aware of this simple attack. The bar one has to jump to compromise an account in this way seems to be set too low, especially when you compare the security with that of a typical online bank, yet it has been shown to work with potential considerable damage.

You may be inclined to think that Dave should simply have turned off notification previews on his phone. However, as I have shown in my “Snaphack” attack, it is still possible to read such messages when victims are simply using their phones, such as when messaging people. They are often unaware of the modus operandi and simply ignore these notifications/warnings. When I tried the PayPal experiment on an Android phone, I found the text message preview was enabled by default and a highlighted area of the message that picked out the confirmation code for me to view it even quicker.

RELATED READING: Mobile payment apps: How to stay safe when paying with your phone

Would FaceID have helped?

One further finding in my hack of Dave’s account was the final straw. In the past I had seen Dave open his iPhone using FaceID, even while wearing a face mask. This was an Apple Watch feature introduced in April 2021 with iOS 14.5 to bypass FaceID and I quickly found a get around at that time. I tested this out on Dave’s phone and as suspected, it worked with ease using my own face and obscured by a face mask. Even though he received a notification on his Apple Watch to say I had unlocked his iPhone, this would be all that would be required to unlock a text preview. This would surely be enough time to read a confirmation code and start the attack.

Phone loss

This got me thinking about phones being stolen. Since phones are packed with tough encryption, I had previously assumed phones were not worth much on the black market and relatively worthless without a follow-up social engineering strike to obtain the Apple or Google reset password. However, I am now thinking anyone’s phone is at risk if the attackers know your email address once they steal it on a train for example. A simple shoulder surfing or light internet research could obtain this information quite quickly and then coupled with what I have discovered, there is a serious amount of damage that could unfold.

Security questions

PayPal still offers security questions and from what I found, I could not remove them, only change the answers. PayPal’s security settings page states that “For your protection, please choose 2 security questions. This way, we can verify it’s really you if there’s ever a doubt.” But bypassing such security questions is often extremely easy within the world of social engineering and the amount of data available about many of us on social media, so it seems crazy that it should be available to gain entry to a finance application.

So why is it so easy?

Banks are continually making it harder for hackers to exploit their systems and often update without our knowledge, keeping our accounts safe. But if we use PayPal as a form of payment assigned to apps such as Uber or eBay, which is constantly linked to our credit cards and bank accounts, isn’t this the weakest link in the chain?

Without wanting to place blame on PayPal, I think there are many prevention techniques you can apply from this story right away. This is by no means PayPal’s fault, but it proves yet another workaround that threat actors will attempt to abuse, and for which we should always be on alert.

Prevention methods

- Do not rely on SMS-based multifactor authentication; wherever possible, use an authenticator app or security key instead

- Never ignore a confirmation code. If you receive one when you haven’t expected it, something is probably up that needs investigating

- Never leave your phone unattended

- Hide previews of all SMS text messages and other app notifications

- If you lose your phone or have it stolen, immediately contact your phone provider to lock the SIM. Then use Apple’s ‘Find My’, or Google’s ‘Find My Device’, to locate the phone and place it in lost mode.

- Use a separate email address for PayPal – one that others will not be able to guess

- Turn off or change your PayPal security answers to random passwords that are unrelated to the question and store them in your password manager

- Remove the option that allows FaceID to work with an Apple Watch while wearing a face mask

Of course, I asked PayPal for a response, so let me leave you with what their representative had to say: “I have reviewed the document you have shared from your end. However, please note that we have educated our users not to share the security code which they received from PayPal to anyone.”