My colleague Jake Moore recently published a blogpost Houseparty – should I stay or should I go now? The post intrigued me, not just for the title taken from the great 1982 song by the Clash. Jake, sensibly, suggests that when you no longer use an app, such as Houseparty, that you delete both the app and the account you created to avoid your personal data being left dormant on a server where it could possibly be prone to being part of the next data breach.

If you think deleting your account deletes all your personally identifiable information (PII) from instant messaging apps, then you may need to think again, and this is probably true for all services that encourage social interaction between friends and request permission to access the contacts on a user’s device to facilitate this. If, like me, you have never used Houseparty, you could be forgiven for assuming that the service does not hold any personal information on you; again, you may need to rethink this.

Your personal data, such as phone number and name, and maybe even email and physical address, may have been uploaded to servers of social media and instant messaging companies when they are granted permission to synchronize contact lists from your friends’ devices.

WhatsApp, the Facebook-owned instant messaging platform that probably boasts the largest user count of any app similar to Houseparty, requests access to contacts. The permission request to access the contacts is required by the app platform providers, such as Apple and Google, and seeks any necessary consent required by local privacy legislation. The WhatsApp privacy policy states, “you provide us, all in accordance with applicable laws, the phone numbers in your mobile address book on a regular basis, including those of both the users of our services and your other contacts”.

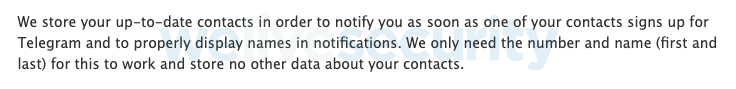

Another app that requests similar permissions is Telegram, a popular instant messaging chat app. The functionality of this app removes any doubt that this service stores the uploaded contact list. After you install the app on your phone and grant access to your contact list, if you install the desktop version the contacts from your phone’s uploaded contact list that also have Telegram accounts become available within the desktop app. The Telegram app asks for permission to “sync your contacts” in a similar way to other apps. The Telegram privacy policy is also very clear about the data being used, in this case phone number, first and last name; see Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) recognizes that a real name or alias is personal information and that a phone number is a “unique personal identifier”, as it is a persistent identifier that can be used to recognize a consumer, a family, or a device that is linked to a consumer or family. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) legally defines a name as personal data but is less clear on phone number. There are differences between the GDPR and CCPA legislation: a significant one is that CCPA not only protects an individual, but extends to households – making the definition of “personal” broader than just an individual.

What about Houseparty?

At the start of the pandemic, a good friend of mine, Kent, and I communicated to organize a virtual social gathering on a Friday evening. He suggested Houseparty; however, we used Facetime due to my preference to not create yet another account. From that original discussion, I knew Kent used Houseparty and had an account; a quick call confirmed he still has the app installed to keep in touch with family and friends. I asked Kent whether he granted Houseparty permission to access his contacts. After initially stating “No, why would I do that?”, we quickly established that he had, as clicking to add a friend through contacts displayed everyone that was in his phone contact list. To exonerate Kent’s actions, it’s worth pointing out that the app does not really function as a social tool unless it has access to your friends, either through Facebook or your uploaded contact list.

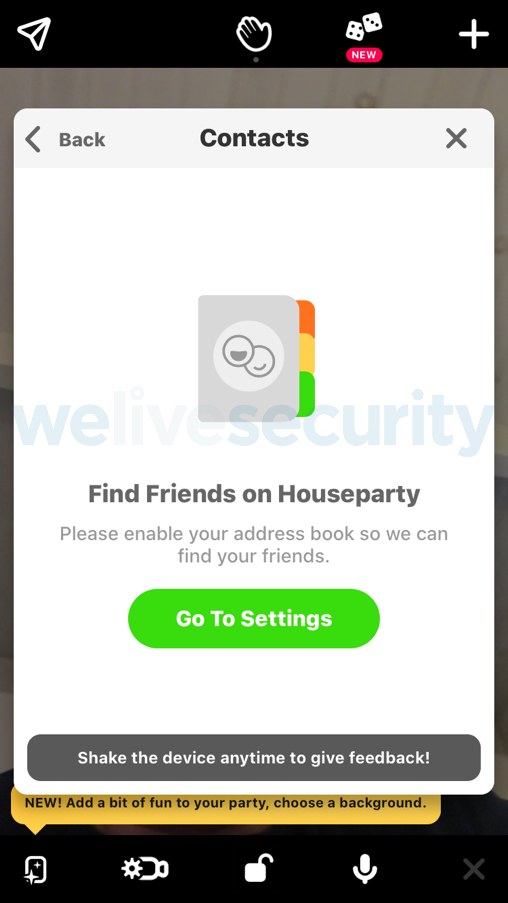

When installing the Houseparty app, there are several options offered to enable the app either to find friends who are already users or to suggest friends and even friends of friends (see Figure 2a below). The main options are to allow access to the contacts stored on your phone or to allow access to your Facebook account, enabling Houseparty to extract your friends list from the social network. The wording in Figure 2a specifically states “your contacts will be uploaded to Houseparty’s servers so that you and others can find friends and to improve your experience”. The privacy-conscious among you are probably making a sighing noise right about now, especially at the inference that others will be introduced to your contacts.

If you skip granting the permission during installation, the app will prompt you again if you click on “contacts” when trying to add friends. Note the change in language and the missing disclosure that the contact list will be uploaded to Houseparty’s servers: see Figure 2b.

Now that we have established that the app potentially exfiltrates all the contact data off your phone and from any connected Facebook account, let’s take a look at the Houseparty privacy policy to establish exactly what they collect and how it’s used.

If you have ever used an app or service that uploads your contact data, you may have witnessed “X has joined” type messages displayed in the app or service. The option to start a conversation or connect to the person is a convenient notification and the very reason that companies request permission to upload contact data to their servers.

Houseparty privacy policy – “What information we collect”

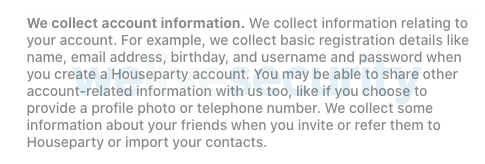

The collection of account information does include a disclosure that “some information” about your friends is collected if you import your contacts; see Figure 3.

Figure 3

And if you link a social media account “certain social media account information” is collected; see Figure 4.

Figure 4

The use of the words “some” and “certain” seems vague when addressing data collection of PII; this is probably by design, as a detailed listing could cause concern, even alarm. The reference to “contacts” being split between the two sections of the policy covering “account information” and “third party accounts and apps” is confusing. What is confirmed, though, is that phone numbers and addresses of your contacts are collected if you grant permission to upload your contacts. I hope by “addresses” they mean email addresses ... or am I being optimistic?

Houseparty privacy policy – “Why we collect information”

The general concept that your contact data is used to assist in connecting with your friends seems perfectly reasonable and logical: see Figure 5. The suggestion of other connections based on your existing friends implies that users are profiled, which again is probably not that surprising for a social networking tool.

Figure 5

Houseparty privacy policy – “How we collect Information”

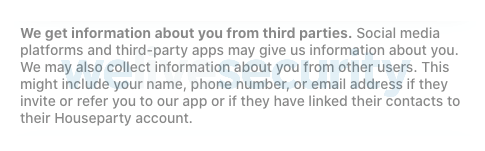

When registering an account, there’s an amount of data required to create the account and there are browser beacons and web cookies and numerous other relatively normal and expected methods of data collection, as you would expect. Figure 6 shows the wording for the section titled “We get information about you from third parties”. Who do they mean by “you”, a user of Houseparty or anyone in the world? A privacy policy needs to be accepted by the people it affects, so is it safe for Houseparty to assume this means it applies only to a Houseparty registered user?

Figure 6

Then we get to the sting in the tail that may answer the questions I have just raised: “We may also collect information about you from other users. This might include your name, phone number, or email address if they invite or refer you to our app or if they have linked their contacts to their Houseparty account”. This establishes that the Houseparty privacy policy applies to a non-Houseparty user and someone who could never have agreed to accept the Houseparty privacy policy. This confirms that they potentially possess my data due to the upload of a “friend’s” contact list.

However, the “you” then becomes confusing when reading the next section on “your choices”, as this then refers to a registered user being able to make decisions in their account setup on such things as marketing preferences.

Taking back my identity

I have established above that my friend Kent uploaded his contact list and, as stated in the Houseparty privacy policy, this includes at least my phone number and name, both of which are classed as PII under the California Consumer Privacy Act. As a resident of California, I am afforded the right to ask what personally identifiable information a company retains and potentially shares about me and, if I so wish, to request deletion of the said data. I made such a request to find out what data they have about me. Here is a summary of the email conversation…

My request – As a resident of California please send me a copy of any data about me that includes my name, email address or phone number.

Houseparty response – The email address you are contacting us from does not reflect any account, and so I can only ask you to please submit a new request using the correct email address you used to register the account.

There is a blatant disconnect between my request and the answer; I asked for data they may have in their possession about me but the response refers to there being no registered account for the data I provided in my request. So I asked again…

My request – I have never had an account and I am requesting confirmation that my personal information is not held on any system in their company.

Houseparty response – Don't worry, I look for your information in our system but I didn't find any account with your phone number or your email, therefore we don't have any data about you.

The disconnect seems to be that I am not a user and therefore there is no data being held on me, yet in reality they have access to Kent’s uploaded contact data which includes my personal information. I never at any time gave consent for them to hold my personal data nor did I agree to their terms of business or privacy policy. Is the data held as part of my friend’s account or has it been merged into a larger data set, is it being used to profile users that enables the introduction of other, as of yet, unknown friends? Is uploaded contact list data deleted when the user who uploaded it deletes their account? The answer is yes, according to the Houseparty support team…

My request – If I give my permission to upload my contacts from my phone can you [Houseparty] confirm what information this will upload, name, email, phone number etc. And if I later decide to delete my account will all this uploaded contact data be deleted with my account?

Houseparty response – First, the app requests permission to read your contacts from your device to crosscheck who in your contacts is already using Houseparty, therefore you will be able to reach out to them since the contact already exists in your device and makes this faster to invite them to be able to communicate with you. Basically, the app reads the name, email and phone number to make those contacts faster to reach out for you. Once you request an account deletion, all information is deleted from the Houseparty account, all your contact's names, emails and phone numbers as well as the information you used to create your own account.

My request – confirmation that contact lists are uploaded and whether if I request account deletion would my contact data be removes from all my friends accounts as well?

Houseparty response – A copy of your whole contacts list is not copied into a server and kept there, but it is accessible to read by the service through the app, once you grant permission for this.

My request – clarification that the upload screen (see figure 2a) on granting permission is incorrect and that the privacy policy is not accurate

Houseparty response – We, as User Support, do not hold the technical specifics of what exactly is held or uploaded into servers, but what I can do for you is to provide the link to our Privacy Policy: then continues So, if the installation screen mentions that the contact list is uploaded, I am unable to guarantee if there is an exact copy of your contacts created and saved in a server, and if it is updated constantly, or just access granted to constantly read the contacts of a user.

Confirming no data is uploaded and then confessing that actually the support team does not know what is uploaded is bad. If you don’t know the facts, then don’t provide an answer!

In Houseparty’s defense, and as we saw at the start of this blogpost, the issue is likely not theirs alone. Any app that uploads contact lists from someone’s device to their own systems or retains access to contact lists potentially suffers from the same issue. And if Houseparty is not uploading and storing contact lists from registered users’ devices, then the company needs to change the wording in its privacy policy and update the messaging displayed in the app. In my experience, companies rarely state they store PII data unless they actually do; why claim you have or do something if you don’t, especially considering the legal liabilities that retaining PII give rise to these days?

Who owns the contact data held on someone’s phone and does the owner of the device have the right to share it with third parties such as Houseparty or Telegram? And should the third party request consent from the contact, me in this case, to retain access to or store the personally identifiable data on their systems?

So, when my colleague Jake suggested deleting unused accounts and apps, he was providing good advice - something I advocate and fully agree with. However, as detailed above, this does not necessarily mean you are avoiding the risk of being part of any data breach that a company, in this scenario Houseparty, Telegram or WhatsApp, may suffer. Your personally identifiable information is likely to remain on servers of social media and instant messaging companies and continue to be accessible to them through linked social media accounts or contact lists of your friends.

In the unpleasant event that a breach were to occur, are they required to send a breach notice not only to registered account holders but to everyone they have data on or whose data they have or had access to? Unfortunately, as far as I can tell, the breach notification is only a requirement that applies to account holders. Privacy legislation and breach notifications should probably extend to all the PII data stored, not only that of account holders.

The takeaway

My takeaway from this is that some instant messaging and social media services are storing my personally identifiable information not only without my consent, but without my knowledge and probably with no mechanism (or even deliberate unwillingness) to allow me to discover if that is the case.