Have you ever needed to enter a password when connecting to a Zoom meeting? If you have, then I feel certain that you’re part of a minority among Zoom users. The host may have consciously set the meeting to need a password with the assumption that the attendees will need to input one when they click the link to join the meeting. Why, if the meeting invitation has a password listed in the details, is it not needed?

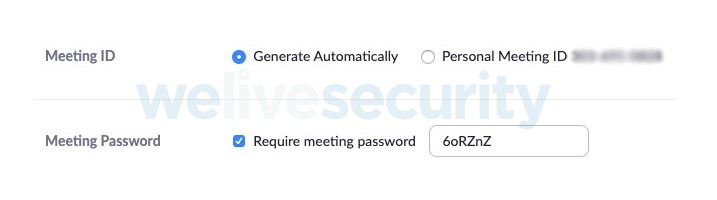

When scheduling a meeting in Zoom, as seen in Figure 1, there’s an option “require meeting password”, which defaults to “on”. Zoom recently changed this from defaulting to “off” in response to the Zoom-bombing issues of uninvited guests joining meetings that some people have experienced. The person scheduling the meeting probably expects that the meeting participants will need the password to connect. After all, when a service asks you to create a password to access an account, it normally asks for that password whenever you log in – that’s the way passwords typically work.

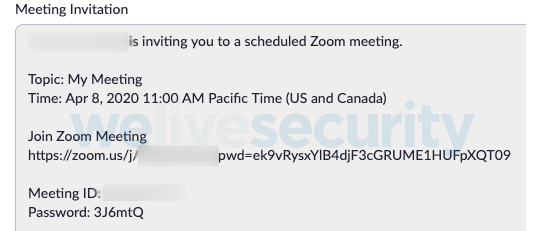

An invitation is generated so you can send details to the intended invitees of how to join the meeting. This invitation includes the date and time, a link to join the meeting, and the Meeting ID and Password, as seen in Figure 2. As the scheduler of several Zoom meetings, at no stage have I been the notified that the invitees will be able to join without inputting the password; my expectation was that they would need the password to join.

Notice the URL in the invitation in Figure 2 to “Join Zoom Meeting” includes a “pwd=” parameter followed by numerous seemingly random characters. The random string is an encoded version of the password, which is listed in its plain form below the Meeting ID. Pointing out the obvious here: the password’s encoded and plain versions are both included in the same invitation that is typically sent, in its entirety, as a calendar invitation or email to the invitee. At this point the obfuscation of the password seems pointless and offers no security value.

The next step is to send the invitation out; if all recipients are within your own company domain, then this is probably secure, as the internal IT team is in control. If sending to a recipient outside of the company, however, the email contents will flow across public networks. The good news here is that 93% of inbound email, according to Google, is encrypted in transit. So, there is limited opportunity someone will intercept the email and glean the meeting details, including the password.

The invitation arrives in the invitee’s inbox or calendar. At the time the meeting is scheduled, a simple click on the link in the invitation is all that’s required to join the meeting. The scheduler is expecting the invitee to need a password, as that was how the invite was configured. No password is required to be input, however, because the password is embedded in the link hidden in the encoded string of characters used to connect to the meeting. What was the point of requiring a password, then?

The other way to join a Zoom meeting is to enter the 9-digit Meeting ID; if you attempt to join a meeting using this method and a password was configured, a password prompt is displayed. This stops people attempting to connect to a password-protected meeting with only the Meeting ID, thus resulting in a reduction of Zoom-bombing. That said, the bad actors who have been Zoom-bombing may still be able to use brute-force tactics to find valid Meeting IDs, by setting scripts running to continually attempt to connect to meetings.

There is a risk that someone may forward the invitation, in its entirety, to an unauthorized person who could then join the meeting, and would be in possession of the link with the embedded password and the actual password. Even if the password were not embedded in the link, the password is included in the invitation, so again the password is offering no security value.

Does the browser insert any risk to the details needed to join a meeting? As the link is https, the browser will start by asking the zoom.us servers for encrypted communication; once established, the full link will be requested and the meeting process will begin, with no password required as it’s embedded in the link. Again, the password has added no value.

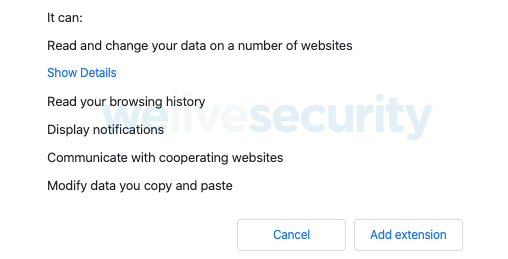

Zoom-bombing was primarily an issue for schools and students, with malicious actors joining video conferences for online teaching and displaying racist or inappropriate messages and content. A student’s device is likely to have other apps or browser extensions installed that allow them to communicate in a fun way, for example emoji or chat extensions. If an extension has permission to read browsing history, then the link with the embedded password can be accessed by extension developers; they could join without knowing the password, but via the user’s browser history.

Popular extensions that students might have could mean your meeting details, including the embedded passwords, are being shared with third parties. To test this, I went to the Chrome Web Store, and with some guidance from my son on what students are using, I attempted to add two Chrome extensions that have in excess of 1 million downloads each. Both asked for the following permission – “Read your browsing history”.

This permission allows these two third-party companies to access all my browsing history, including the links to any Zoom meetings that have been joined, and will include by default the embedded password. I have not named the extensions I attempted to add to my browser, since the companies concerned may have legitimate reasons to collect the data and may be storing it securely. However, they may also be sharing it with other third parties and not be securing it properly.

If the meeting is created using Zoom’s default settings and is on a recurring schedule, then the invitation link, including the password, may be shared with extension providers and any third parties they share data with. I doubt this possibility was considered by the person scheduling the meeting; they thought a password would be required.

Zoom does offer the ability to switch off the “embedded password” feature. However, this option is not an option at the time when a meeting is created; instead it requires the user to change the defaults in their “Personal – Settings”.

In my opinion, when a user creates a meeting, Zoom should display a notification alert that using the default setting of “require password” actually means that no password entry will be required by anyone, including any third party, who has the link to the meeting.

What else?

Make no mistake, there’s more to consider when it comes to protecting your Zoom meetings. Read our deep dive into the app’s settings and learn what else you can do to keep the service more secure.

ESET has been here for you for over 30 years. We want to assure you that we will be here in order to protect your online activities during these uncertain times, too.

Protect yourself from threats to your security online with an extended trial of our award-winning software.

Try our extended 90-day trial for free.