In the new cryptomining module we discovered and described in our previous article, the cybercriminals behind the Stantinko botnet introduced several obfuscation techniques, some of which have not yet been publicly described. In this article, we dissect these techniques and describe possible countermeasures against some of them.

To thwart the analysis and avoid detection, Stantinko’s new module uses various obfuscation techniques:

- Obfuscation of strings - meaningful strings are constructed and only present in memory when they are to be used

- Control-flow obfuscation - transformation of the control flow to a form that is hard to read and the execution order of basic blocks is unpredictable without extensive analysis

- Dead code - addition of code that is never executed; it also contains exports that are never called. Its purpose is to make the files look more legitimate to prevent detection

- Do-nothing code – addition of code that is executed, but that has no material effect on the overall functionality. It is meant to bypass behavioral detections

- Dead strings and resources - addition of resources and strings with no impact on the functionality

Out of these techniques, the most notable are obfuscation of strings and control-flow obfuscation; we will describe them in detail in the following sections.

Obfuscation of strings

All the strings embedded in the module are unrelated to the real functionality. Their source is unknown and they either serve as building blocks for constructing the strings that are actually used or they are not used at all.

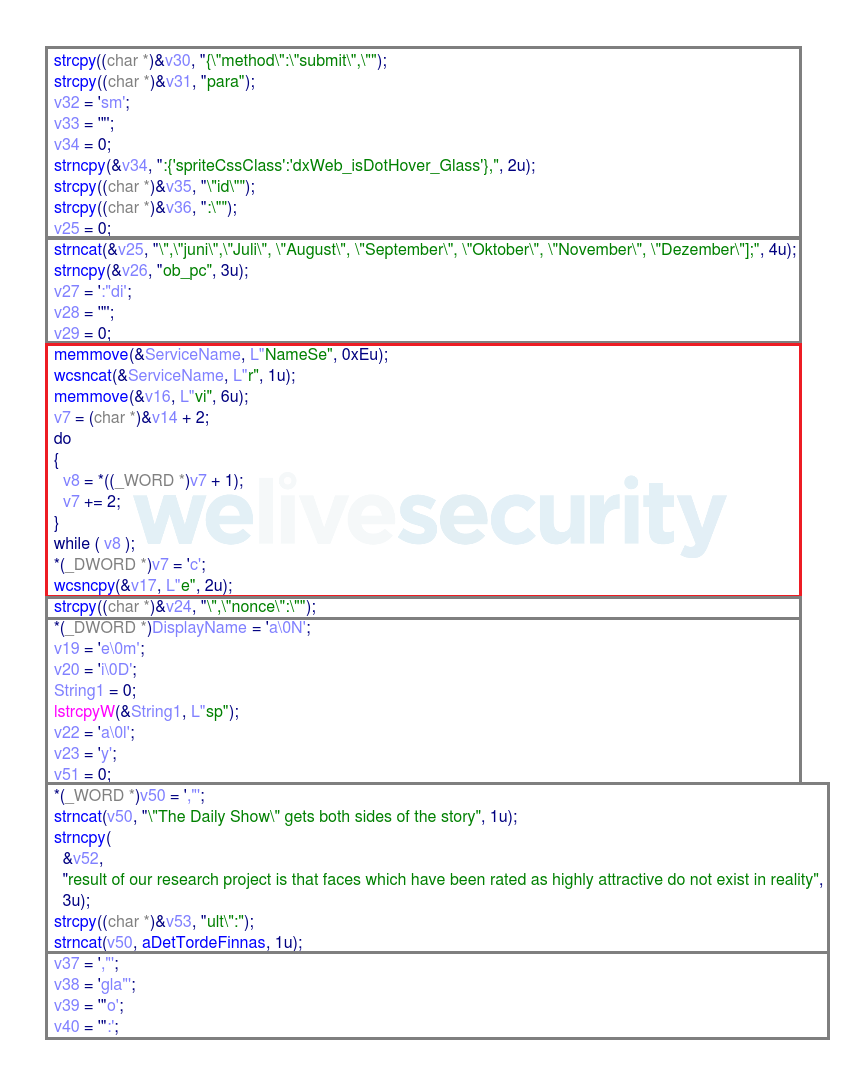

The actual strings used by the malware are generated in memory in order to avoid file-based detection and thwart analysis. They are formed by rearranging bytes of the decoy strings – those embedded in the module – and using standard functions for string manipulation, such as strcpy(), strcat(), strncat(), strncpy(), sprintf(), memmove() and their Unicode versions.

Since all the strings to be used in a particular function are always assembled sequentially at the beginning of the function, one can emulate the entry points of the functions and extract the sequences of printable characters that arise to reveal the strings.

Figure 1. Example of string obfuscation. There are 7 highlighted decoy strings in the image. For example, the one marked in red generates the string “NameService”.

Control-flow flattening

Control-flow flattening is an obfuscation technique used to thwart analysis and avoid detection.

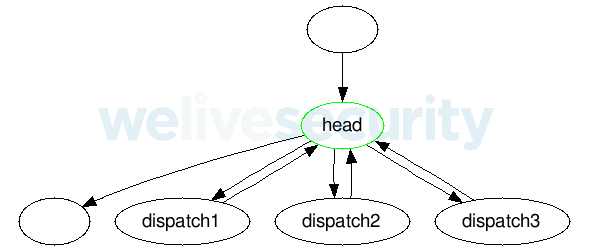

Common control-flow flattening is achieved by splitting a single function into basic blocks. These blocks are then placed as dispatches into a switch statement inside of a loop (i.e. each dispatch consists of exactly one basic block). There is a control variable to determine which basic block should be executed in the switch statement; its initial value is assigned before the loop.

The basic blocks are all assigned an ID and the control variable always holds the ID of the basic block to be executed.

All the basic blocks set the value of the control variable to the ID of its successor (a basic block can have multiple possible successors; in that case the immediate successor can be chosen in a condition).

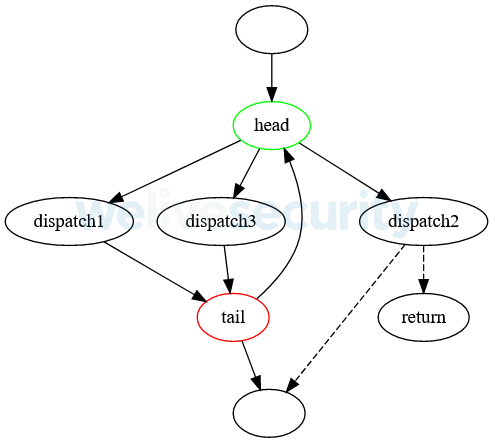

Figure 2. Structure of common control-flow-flattening loop

There are various approaches to resolving this obfuscation, such as using IDA’s microcode API. Rolf Rolles used this method to identify these loops heuristically, extract the control variable from each flattened block and rearrange them in accordance with the control variables.

This – and similar – approaches would not work on Stantinko’s obfuscation, because it has some unique features compared to common control-flow-flattening obfuscations:

- Code is flattened on the source code level, which also means the compiler can introduce some anomalies into the resulting binary

- The control variable is incremented in a control block (to be explained later), not in basic blocks

- Dispatches contain multiple basic blocks (the division may be disjunctive, i.e. each basic block belongs to exactly one dispatch, but sometimes the dispatches intertwine, meaning that they share some basic blocks)

- Flattening loops can be nested and successive

- Multiple functions are merged

These features show that Stantinko has introduced new obstacles to this technique that must be overcome in order to analyze its final payload.

Control-flow flattening in Stantinko

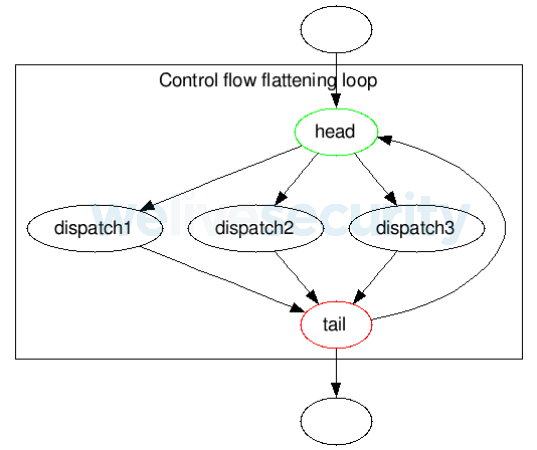

In most of Stantinko’s functions, the code is split into several dispatches (described above) and two control blocks — a head and a tail — that control the flow of the function.

The head decides which dispatch should be executed by checking the control variable. The tail increases the control variable by a fixed constant and either goes back to the head or exits the flattening loop:

Figure 3. Regular structure of Stantinko’s control-flow-flattening loop

Stantinko appears to be flattening code of all functions and bodies of high-level constructs (such as a for loop), but sometimes it also tends to choose seemingly random blocks of code. Since it applies the control-flow-flattening loops on both functions and high-level constructs, they can be naturally nested and there happen to be multiple consecutive loops too.

When a control-flow-flattening loop is created by merging code of multiple functions, the control variable in the resulting merged function is initialized with different values, based on which of the original functions is called. The value of the control variable is passed to the resulting function as a parameter.

We overcame this obfuscation technique by rearranging the blocks in the binary; our approach is described in the next section.

It’s important to note that we observed multiple anomalies in some of the flattening loops that make it harder to automate the deobfuscation process. The majority of them seem to be generated by the compiler; this leads us to believe that the control-flow-flattening obfuscation is applied prior to compilation.

We witnessed the following anomalies; they can appear separately or in combination:

- Some dispatches can be just dead code – they will never be executed. (Examples in the section “Dead code inside the control-flow-flattening loop” below.)

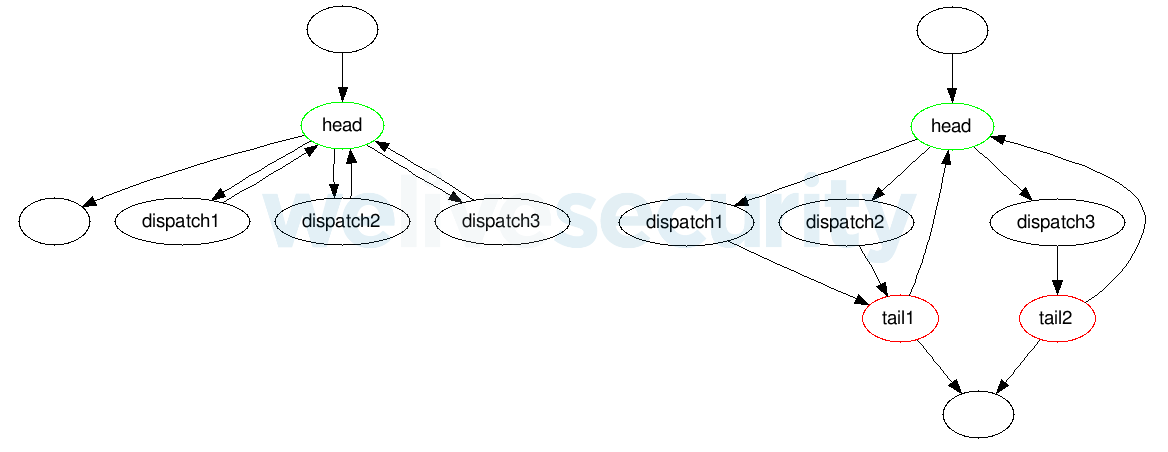

- Basic blocks inside of dispatches may intertwine, this means that they can contain joint code.

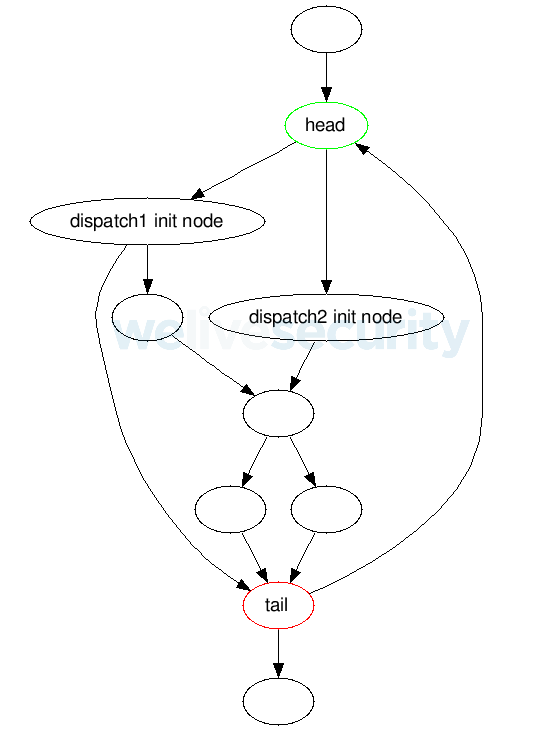

Figure 4. Structure of a flattening loop with dispatches sharing joint code

- There are direct jumps from dispatches to a block outside the flattening loop, right behind the tail, and to blocks that return from the function.

Figure 5. Structure of a flattening loop whose dispatch breaks directly out of the loop. Only one of the dashed lines occurs.

- There can be multiple tails, or no tail at all – in the latter case, the control variable is increased at the end of each dispatch.

Figure 6. Structure of a flattening loop without any tail (left) and with multiple tails (right)

- The head doesn’t contain a jump table right away. Instead, there can be multiple jump tables and there’s a sequence of branches, prior to the jump tables, binary-searching for the correct dispatch.

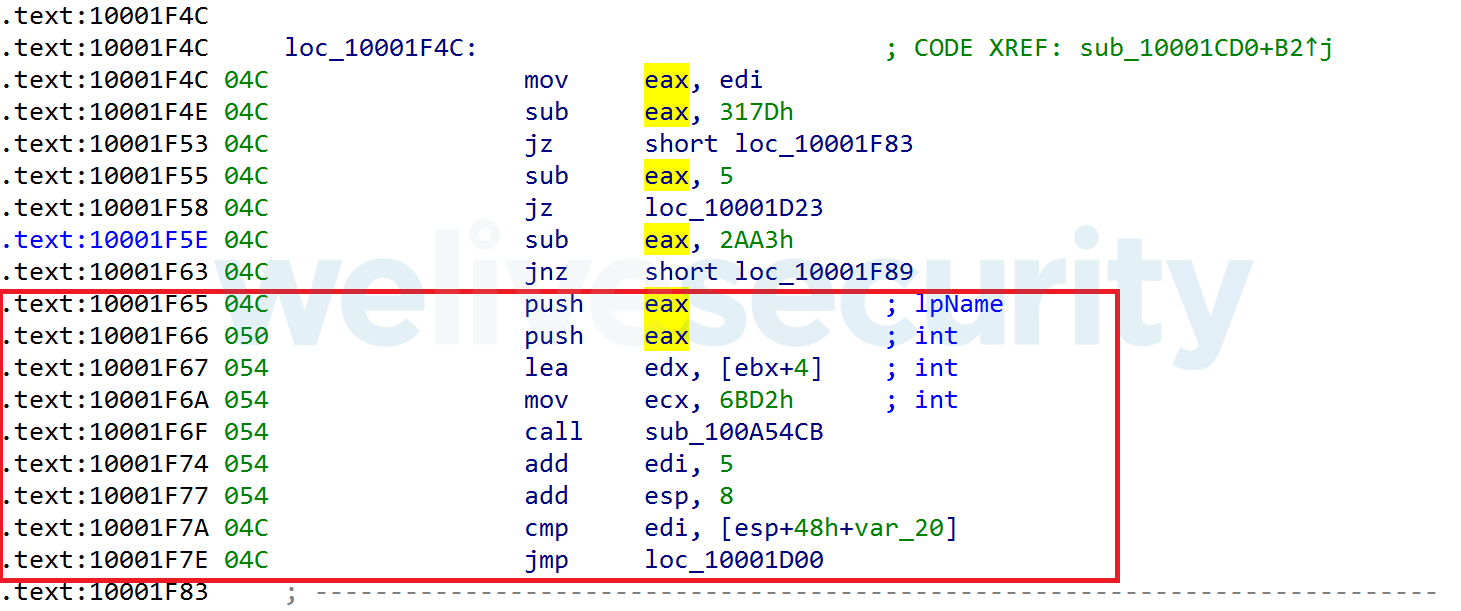

- The value of the control variable might be used inside of the dispatches; this means that the control value has to be preserved/computed even in the deobfuscated code.

Figure 7. The EDI register contains the control variable that is passed to EAX and used inside the dispatch. The dispatch is highlighted with red.

- Sometimes, the tail contains instructions that are crucial to restoring the correct values of registers and local variables. During deobfuscation, we remove the tail, so we must make sure these instructions are executed after each dispatch, even if they are not part of it.

- There are cases where there is no dispatch whose ID is, at that moment, equal to the current value of the control variable.

Deobfuscation

Our goal is to build a deobfuscation function able to rearrange the code on the binary level to make it easily readable for a reverse engineer, while keeping the resulting code executable. It has to be able to recognize all basic blocks belonging to each dispatch and to copy and move them arbitrarily.

During basic block manipulation one has to make sure to recalculate relative addresses of branch targets and addresses forming legitimate jump tables correctly.

Our solution doesn’t take relocations into account; hence one always needs to make sure that the sample is loaded at the same base address.

We used a reverse-engineering framework that provides us with some useful features, such as assembly manipulation and a symbolic execution engine.

The core parameters of the function are the addresses of the control blocks (head and tails), range and step of the control variable, names of the registers, and the memory locations containing the control variable, control_locations, and, lastly, the address of the first basic block following the loop, which we define as next_block. It obviously also requires the address of the function to be deobfuscated and the address where the deobfuscated function should be placed.

We expect multiple tails due to anomaly 4 above.

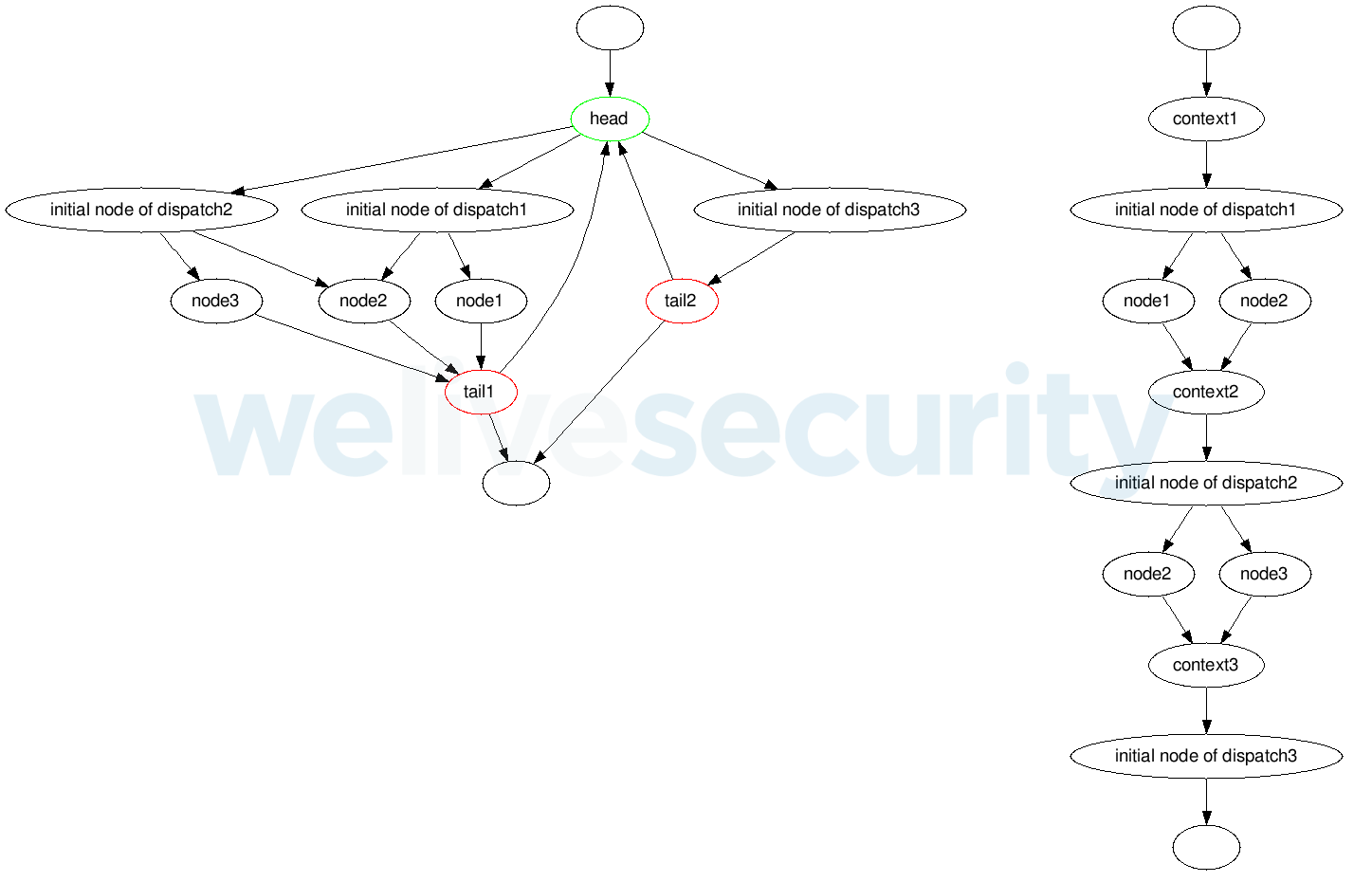

The deobfuscation function iterates through the range of the control variable by its step value to simulate the real control-flow-flattening loop; in each iteration, the function starts by generating a context to deal with anomalies 6 and 7. The context is to be placed before the respective dispatch.

The context is a basic block containing instructions assigning registers and memory addresses and keeping control_locations updated. The context of the first iteration just preserves the value of the control variable. (Note: no context is required to deal with anomaly number 4.)

The last basic blocks of the previous dispatch (or, in case of the first dispatch, the basic blocks right before the head) are redirected to the created context.

The initial basic block of a dispatch that is to be executed (in each of the iterations) is determined by the current value of the control variable (dispatch ID).

The actual basic block is found by symbolically executing the binary-search algorithm, which searches for a basic block with the current ID. The initial state of the symbolic execution contains control_locations assigned to the current value of the control variable.

We stop the symbolic execution at the first basic block that (i) contains an unconditional branch, or, (ii) has a destination that cannot be determined by the control variable.

One could also emulate this part or use a framework that would be able to simplify the binary-search algorithm into a jump table and then convert that into a switch statement instead. These methods deal with anomaly 5.

In case there’s no dispatch for a particular ID, the loop just continues and increases the control variable due to anomaly 8.

The whole dispatch (i.e., each basic block that is reachable from its initial basic block to its head, tail(s) or next_block) is then copied after the preceding context block (as described above). It cannot be just moved due to anomaly 2.

There are currently two uncommon cases that can occur due to anomaly 3; both result in premature termination of the iteration. The cases happen when a dispatch:

- Returns from the function

- Points to next_block

Finally, when the iteration ends, the last basic blocks of the previous dispatch (or basic blocks right before the head, in case of the first dispatch), are redirected to the first basic block outside the flattening loop.

This method solves anomaly 1 automatically, since the dead dispatches won’t be copied into the resulting code.

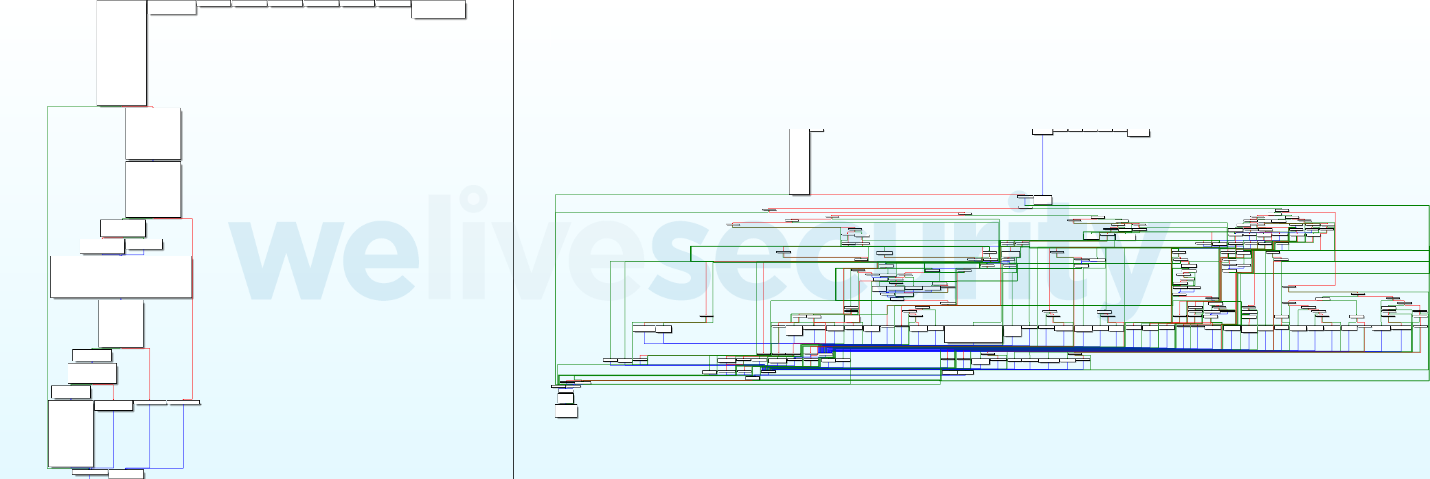

Figure 8. Example of an obfuscated function (left) and its deobfuscated counterpart (right). The dispatches are executed in this order: dispatch1 → dispatch2 → dispatch3.

These changes are then written to the virtual address where the deobfuscated function should be placed.

In case we are dealing with flattening of merged functions, we point references to the target function having the identical initial value of the control variable in the parameter, to the address of the new deobfuscated function.

Figure 9. Example of obfuscated (right) and deobfuscated (left) control flow graph

Possible improvements

The approach described above operates exclusively at the assembly level, which isn’t sufficient to make the deobfuscation fully automated.

The reason is that accurate recognition of all patterns is rather difficult, mostly due to various compiler optimizations present in the source code level obfuscations. The pattern recognition is necessary in our case, for example, to automatically fill in the parameters of the core deobfuscation function.

The advantage of this approach is that the resulting code can be executed right away and one can use arbitrary reverse-engineering tools for further analysis.

This approach could be further improved by the use of a progressive intermediate representation (IR), which provides optimization techniques that would, among other things, get rid of most of the anomalies generated by compilers, and thus allow automated recognition of the parameters required by the deobfuscation function.

One could also use the selected IR for both recognition and the deobfuscation of which the latter, in our case, consists of rearranging of basic blocks.

The drawback of this option is that the resulting code would also be in the IR, which means that the consecutive analysis would have to be done with the IR as well. The number of tools working with the IR and their functionality could be rather limited, especially when it comes to visualization. Due to this, it’d be hard to analyze a more complex sample, especially when there are additional layers of obfuscation. We wouldn’t be able to execute the resulting code either.

Dead code

By “dead code” we mean code that either is never executed, or has no overall impact on the functionality. The malware contains dead code mostly in the flattened loops (effectively removed by our above-explained deobfuscation function), but there are also, for example, unused exports and there’s no way to distinguish the unused exports from the legitimate ones.

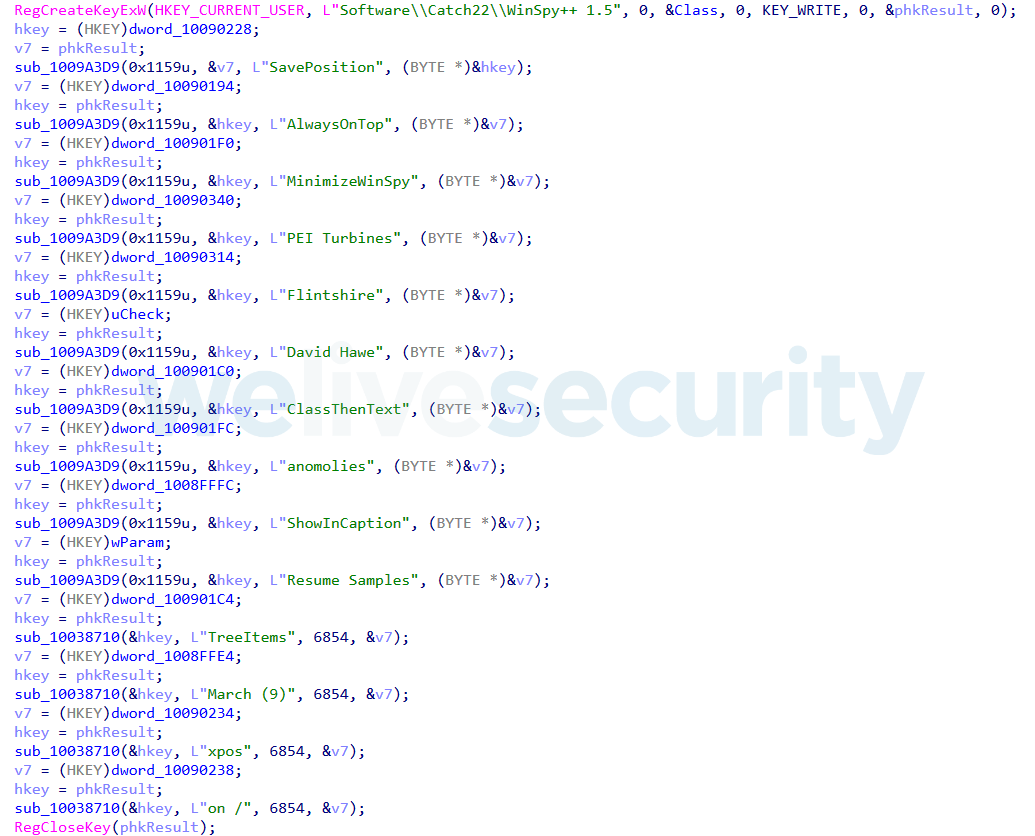

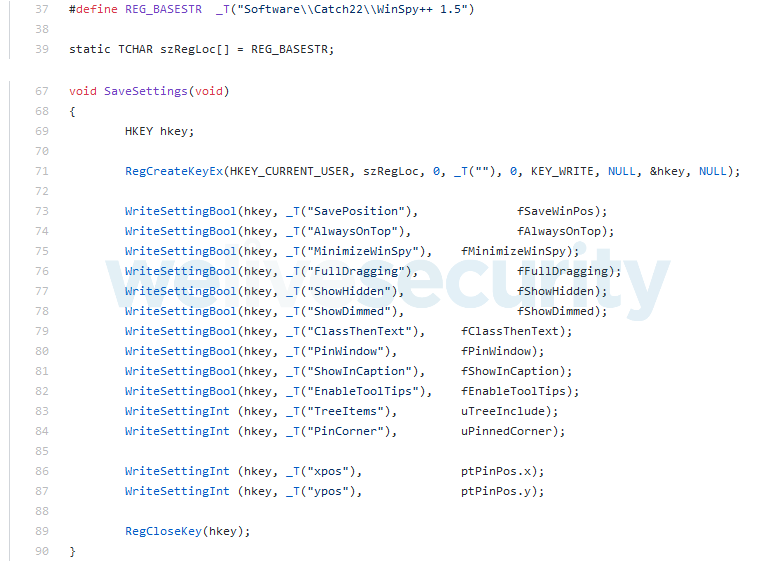

As for dead code in the flattened loop: for Stantinko, it is always inside the dispatches that are never executed. It may contain modified parts of legitimate software such as WinSpy++ (see the example below) that was obfuscated in the same way.

Figure 10. Deobfuscated part of dead code inside a dispatch containing legitimate WinSpy++ code

Figure 11. The equivalent part of code (as in Figure 10) in the official release of WinSpy++

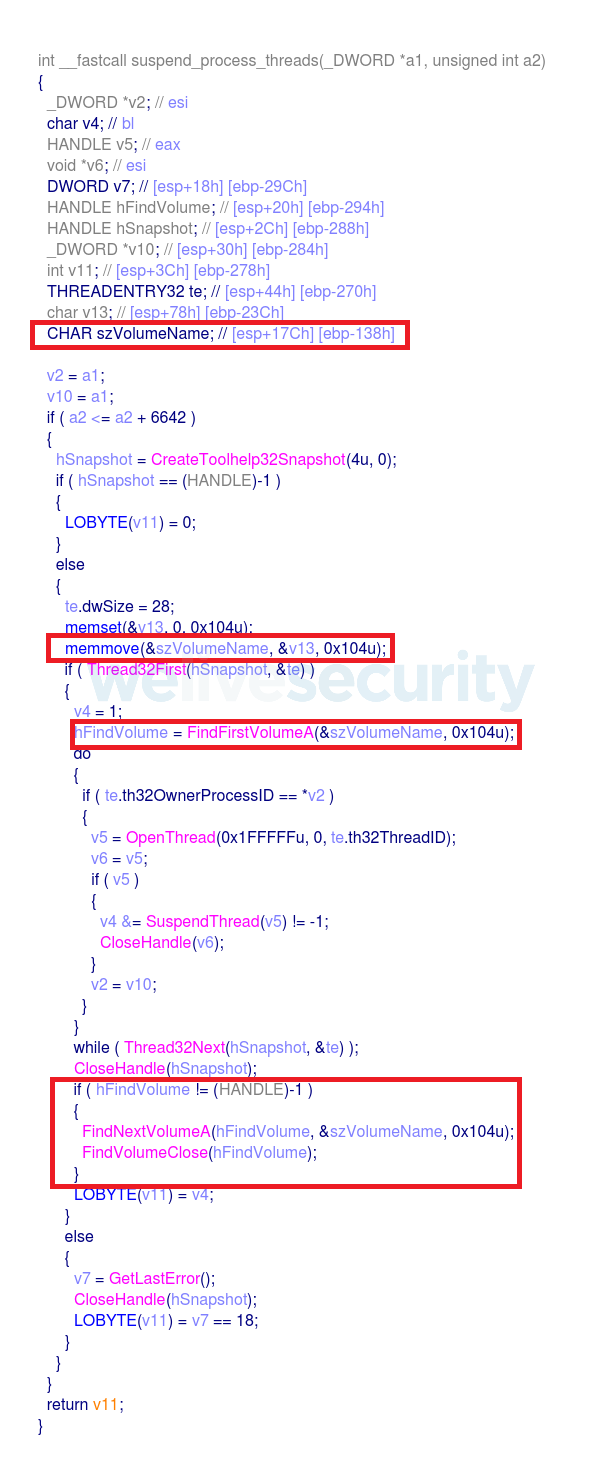

Do-nothing code

Even after the unflattening operation, there are parts of code that have no purpose at all, intermingled with the lines of the “real code”. This is probably meant to obscure the analysis even more or to bypass behavioral detection.

Figure 12. Marked parts are redundant code that iterates through the first two disk volume names and then does nothing with the returned values

Since the code isn’t much harder to read, we decided not to take any actions and analyzed the code at this point.

To optimize out this do-nothing code in general: we’d have to, for example, generate disjunct slices containing all the Windows API calls that are present. The slicing criterion would consist of all the parameters of the calls in each disjunct slice.

Subsequently we’d execute the slices with a prepared call stack in a controlled environment and we’d consider a slice to be functional if it does at least one of the following:

- make some changes to the underlying OS

- require an initial value of a function parameter or a global variable to be known

- assign a value of a function parameter or a global variable

- directly affect overall control flow of the function

Conclusion

The criminals behind the Stantinko botnet are constantly improving and developing new modules that often contain non-standard and interesting techniques.

We have described their new cryptomining module previously; for the module's functional analysis, refer to our November 2019 blogpost. This module displays several obfuscation techniques aimed at protecting against detection and thwarting analysis. We analyzed the techniques and described a possible approach to deobfuscating some of these techniques.

Note: For IoCs and the list of techniques mapped to the MITRE ATT&CK taxonomy, please refer to our previous article describing this cryptominer’s functionality.