UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) security has been a hot topic for the past few years, but, due to various limitations, very little UEFI-based malware has been found in the past. After having discovered the first UEFI rootkit in the wild, known as LoJax, we set out to build a system that would enable us to explore the vast UEFI landscape in an efficient way – and reliably spot emerging UEFI threats.

Using the telemetry gathered by ESET’s UEFI scanner as a starting point, we devised a custom processing pipeline for UEFI executables that leverages machine learning to detect oddities among the incoming samples. This system, besides showing strong capabilities in identifying suspicious UEFI executables, offers real-time monitoring of the UEFI landscape, and would reduce the workload of our analysts by up to 90 percent if all samples had to be analyzed manually.

Hunting for UEFI threats using our processing pipeline, we uncovered multiple interesting UEFI components, which can be divided into two categories – UEFI firmware backdoors and OS-level persistence modules. The most notable out of our discoveries is the so-called ASUS backdoor, a UEFI firmware backdoor found in several ASUS laptop models and remediated by ASUS following our notification.

What is UEFI?

UEFI is a specification defining the interface that exists between the OS and the device’s firmware. It defines a set of standardized services, called “boot services” and “runtime services”, that are the core APIs available in UEFI firmware. UEFI is a successor to the legacy BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) firmware interface, introduced to address the technical limitations of BIOS.

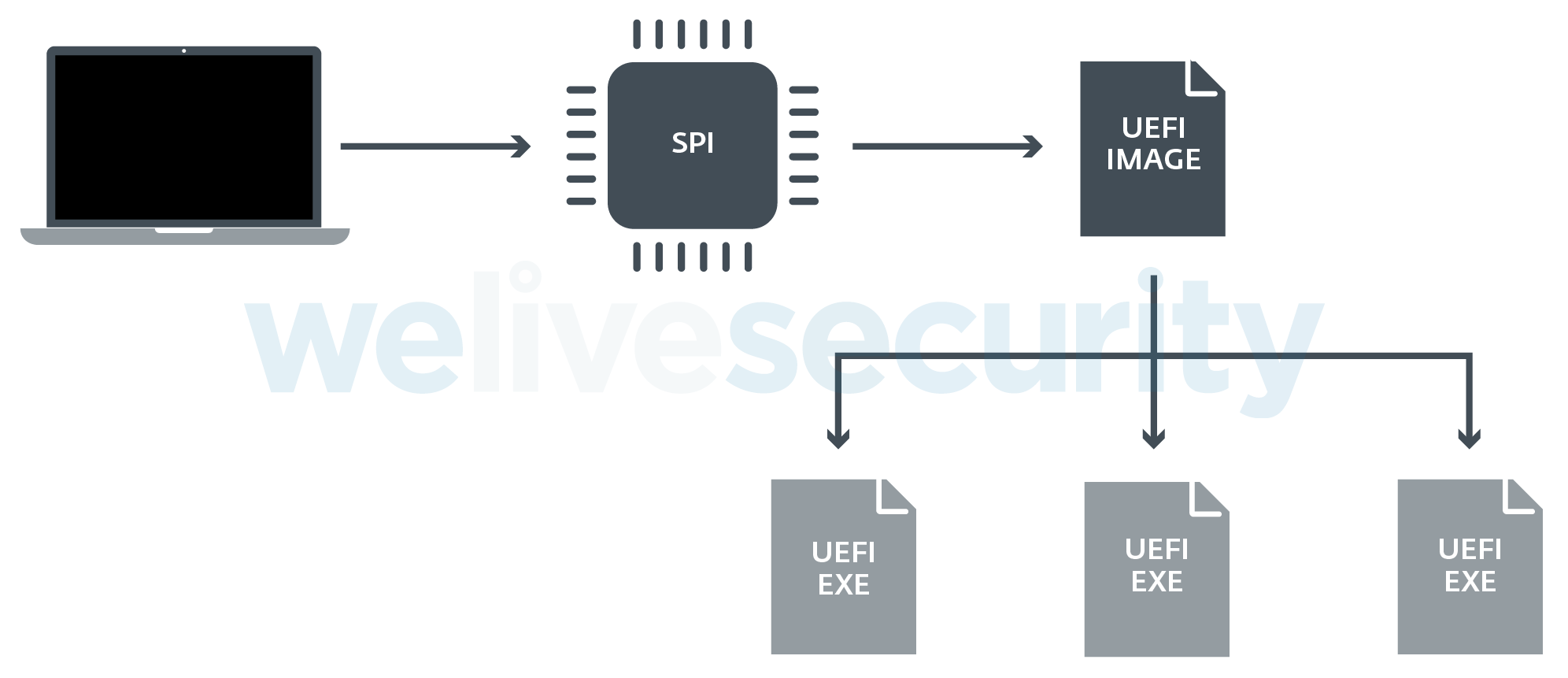

The UEFI firmware is stored in SPI flash memory, which is a chip soldered on the system’s motherboard. Thus, reinstalling the operating system or replacing the hard drive doesn’t affect the firmware code. UEFI firmware is very modular: it usually contains dozens, if not hundreds, of different executables/drivers.

Figure 1. How UEFI executables/drivers are stored in a PC

UEFI as an attack vector

There are multiple ways firmware can be modified, compromising the security of the affected computer.

The first, and most common, option is modification of the firmware by the computer vendor to enable remote diagnostic or servicing, which, if implemented improperly, can serve as a backdoor. Another option is malicious flashing via manual tampering, when the attacker has physical access to the affected device. The third option: remote attacks using malware capable of modifying the firmware.

This third option was documented in our research on LoJax, the first UEFI rootkit to be detected in the wild. In a campaign targeting government organizations in the Balkans as well as in Central and Eastern Europe, the Sednit APT group successfully deployed a malicious UEFI module on a victim’s system. This module is able to drop and execute malware on disk during the boot process – a particularly invasive persistence method that will not only survive an OS reinstall, but also a hard disk replacement.

A machine-learning method to explore the UEFI landscape

Finding malware like LoJax is rare – there are millions of UEFI executables in the wild and only a tiny portion of them are malicious. We have seen over 2.5 million unique UEFI executables (out of a total of six billion) over the past two years alone. Since it is not feasible to analyze each of them manually, we needed to come up with an automated system to reduce the number of samples that require human attention. To address this problem, we decided to build a system tailored to highlight outlier samples by finding unusual characteristics in UEFI executables.

In our research, we examined and compared multiple approaches of every part of the process – from feature extraction, text embedding, embedding multidimensional data through efficient storage, and querying of samples' neighborhoods to generate a final scoring algorithm – all while considering performance and real-time capabilities of the techniques chosen. Once we established an efficient method of retrieving the nearest neighbors to any incoming UEFI binary, we set up a system for assigning similarity scores in the range of zero to one to the incoming executables, comparing them to previously seen files. Files with the lowest similarity score are then inspected with highest priority by an analyst.

As a proof of concept, we tested the resulting system on known suspicious and malicious UEFI executables that were not previously included in our dataset– most notably the LoJax UEFI driver. The system successfully concluded that the LoJax driver was very dissimilar to anything we had seen before, assigning it a similarity score of 0.

This successful test gives us a degree of confidence that if another similar UEFI threat emerged, we would be able to identify it as an oddity, promptly analyze it and create a detection as needed. Besides this, our ML-based approach can reduce the workload of our analysts by up to 90% (if they were to analyze every incoming sample). Finally, thanks to the fact that each new incoming UEFI executable is added to the dataset, processed, indexed and taken into consideration for the next incoming samples, our solution offers real-time monitoring of the UEFI landscape.

A hunt for unwanted UEFI components

Having tested our processing pipeline on known malicious samples, it was time to start hunting for unwanted UEFI modules in the wild. The interesting components that we found can be grouped into two categories – UEFI firmware backdoors and OS-level persistence modules.

UEFI firmware backdoors

So what are UEFI firmware backdoors? In most UEFI firmware setups, options are available to password-protect the system from unauthorized access during the early stages of the boot process. The most common options allow setting passwords to protect access to the UEFI firmware setup, to prevent the system from booting and to access the disk. UEFI firmware backdoors are mechanisms that allow bypassing these protections without knowing the user-configured password.

While such UEFI firmware backdoors are very common – mainly used as a recovery mechanism in case the computer’s owner forgets the password – they come with a number of security implications. Besides allowing attackers with physical access to the affected computer to bypass various security mechanisms, they also create a false sense of security in users who are unaware of them and may believe their computers are unbootable by anyone who doesn’t possess the password.

The most prevalent of the UEFI firmware backdoors we analyzed is the so-called ASUS backdoor. Our research confirmed that at least six ASUS laptop models were shipped with the backdoor; the number, however, is likely much higher (manually checking the presence in every ASUS laptop model was out of the scope of our research). Following our notification to ASUS about the backdoor in April 2019, the vendor removed the issue and released firmware updates on June 14th, 2019.

OS-level persistence modules

The remainder of our findings are OS-level persistence modules – firmware components responsible for installing software at the operating system level. With these persistence modules, the main security problem is that – due to the complicated nature of delivering firmware updates – a computer shipped with a vulnerable firmware component will most likely remain vulnerable during its whole lifetime. For this reason, we believe firmware persistence should be avoided as much as possible and limited to cases where it is strictly necessary, as is the case with anti-theft solutions.

To learn more about our research, please refer to the full paper, A machine-learning method to explore the UEFI landscape.