Most reverse engineers would agree that quite often one can learn something new on the job. However, it is not every day you learn how to cook a delicious meal while analyzing malware. This unique experience is provided by a malware family we discuss in this blog post – Casbaneiro.

Characteristics

Casbaneiro, also known as Metamorfo, is a typical Latin American banking trojan that targets banks and cryptocurrency services in Brazil and Mexico (Figure 1). It uses the social engineering method described in the introduction to our previous article, where fake pop-up windows are displayed. These pop-ups try to persuade potential victims to enter sensitive information; if successful, that information is then stolen.

Figure 1. Countries affected by Casbaneiro

The backdoor capabilities of this malware are typical of Latin American banking trojans. It can take screenshots and send them to its C&C server, simulate mouse and keyboard actions and capture keystrokes, download and install updates to itself, restrict access to various websites, and download and execute other executables.

Casbaneiro collects the following information about its victims:

- List of installed antivirus products

- OS version

- Username

- Computer name

- Whether any of the following software is installed:

- Diebold Warsaw GAS Tecnologia (an application to protect access to online banking)

- Trusteer

- Several Latin American banking applications

Although there seem to be at least four different variants of this malware, the core of all of them is almost identical to the code in this GitHub repository. However, it is practically impossible to separate them from each other, mainly because some variants using different versioning use the same string decryption key, and the same mechanisms are used in different variants.

Moreover, the differences are not important from the functionality point of view. Therefore, we will refer to all these variants as Casbaneiro.

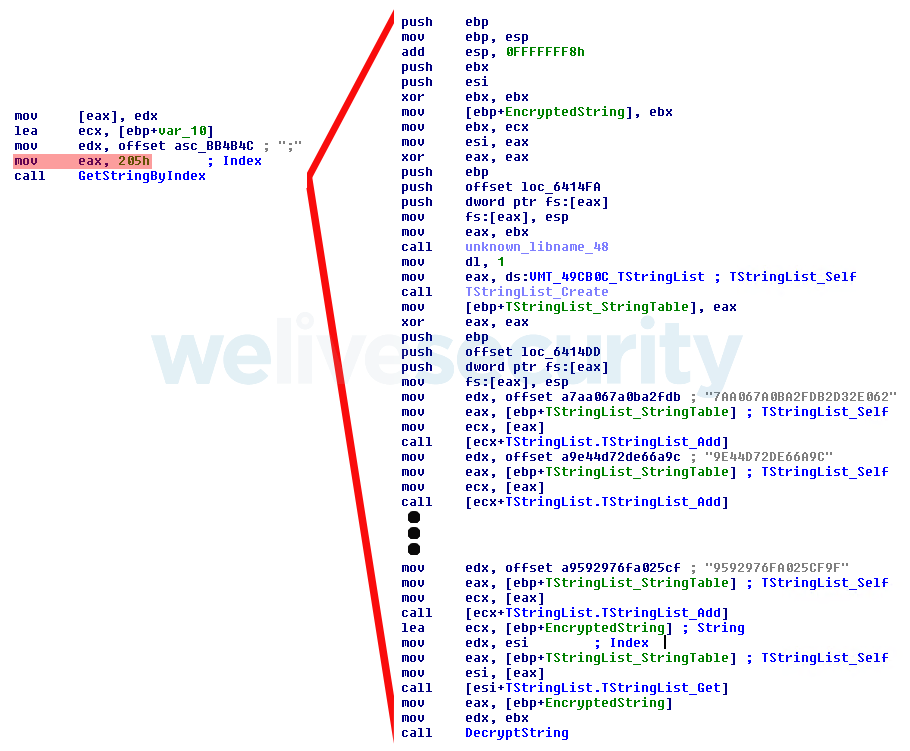

Casbaneiro is easy to identify by its use of a huge string table, with several hundred entries. Strings are retrieved by accessing this table by index. Curiously, whenever the malware needs to obtain a string, the whole string table is constructed in memory from stored chunks of encrypted text, the desired string is decrypted and the whole table is discarded again. You can see an example in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Casbaneiro obtaining a string by index (0x205) and decrypting it

There are strong indicators that this malware family is closely connected to Amavaldo, which we described in our first post in this series about Latin American banking trojans. We will mention these similarities later in this article.

Hijacking clipboard data

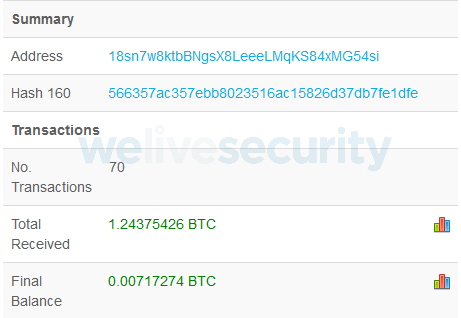

Casbaneiro can also try to steal victim’s cryptocurrency. It does so by monitoring the content of the clipboard and if the data seem to be a cryptocurrency wallet, it replaces them with the attacker’s own. This technique is not new; it has been used by other malware in the past – even the infamous BackSwap banking trojan implemented it in its earliest stages.

The attacker’s wallet is hardcoded in the binary and we have encountered only one. By examining it, we can see payments were already made at the time of writing.

Figure 3. Detail of the attacker's bitcoin wallet

Cryptography

Casbaneiro utilizes several cryptographic algorithms, each one to protect a different type of data. We describe them in the following sections.

Command encryption

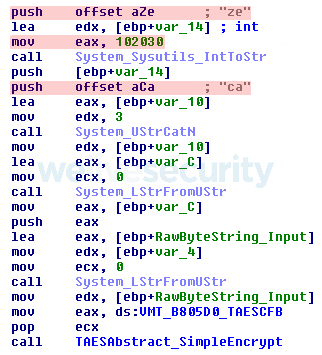

Commands received from the C&C server are encrypted using AES-256. The SynCrypto Delphi library is used. The AES key is derived via SHA-256 from a password stored in the binary. It is not stored as a string but concatenated from separate pieces at runtime, as you can see in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Constructing the password "ze102030ca” used to derive the AES key

String encryption

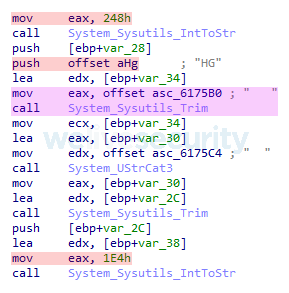

The algorithm used to encrypt strings, comes from this book and is used in other Latin American banking trojans as well. Pseudocode of the decryption algorithm can be seen in Figure 5. The same key is used for all strings. Similar to the command encryption, the key is again concatenated from parts at runtime, only this time it consists of many more parts (see Figure 6). Notice how whitespace strings are added as well, but trimmed later on, therefore having no impact.

def decrypt_string(data_enc, key):

data_dec = str()

data_enc = unhexlify(data_enc)

prev = data_enc[0]

for i, c in enumerate(data_enc[1:]):

x = c ^ key[i % len(key)]

if x < prev:

x = x + 255 - prev

else:

x -= prev

prev = c

data_dec += chr(x)

return data_decFigure 5. String decryption pseudocode

Figure 6. Part of code that concatenates the string decryption key shown in Figure 5. The valid key parts are marked red. The obfuscation by whitespace strings is marked purple.

Payload encryption

In some Casbaneiro campaigns, the actual banking trojan is encrypted and associated with an injector. The algorithm used to decrypt the main payload binary in such cases is exactly the same as the Amavaldo injector uses. Pseudocode is found in Figure 7.

Remote configuration data encryption

Finally, a fourth algorithm is used to decrypt configuration data not stored in the binary file but obtained remotely. We provide examples of such situations below.

You can clearly see in Figures 7 and 8 that this and the payload decryption algorithms are almost identical, only one uses plaintext and the other one ciphertext to update the key. We strongly suspect that the author rewrote the code by hand from the same source and made a mistake in one of the cases.

def decrypt_payload(data_enc, key1, key2, key3):

data_dec = str()

for c in data_enc:

x = data_enc[i] ^ (k3 >> 8) & 0xFF

data_dec += chr(x)

key3 = ((x + key3) & 0xFF) * key1 + key2

return data_decFigure 7. Payload decryption algorithm

def decrypt_remote_data(data_enc, key1, key2, key3):

data_dec = str()

for c in data_enc:

x = data_enc[i] ^ (k3 >> 8) & 0xFF

data_dec += chr(x)

key3 = ((data_enc[i] + key3) & 0xFFFF) * key1 + key2

return data_decFigure 8. Remote data decryption algorithm

Distribution

We believe that a malicious email is usually at the beginning of Casbaneiro distribution chains. Some campaigns were described by FireEye, Cisco and enSilo. If you have read our previous article, you may notice that the campaign described by Cisco uses a PowerShell script very similar to the one utilized by Amavaldo. Even though some parts differ, both scripts clearly come from a common source and use the same obfuscation methods.

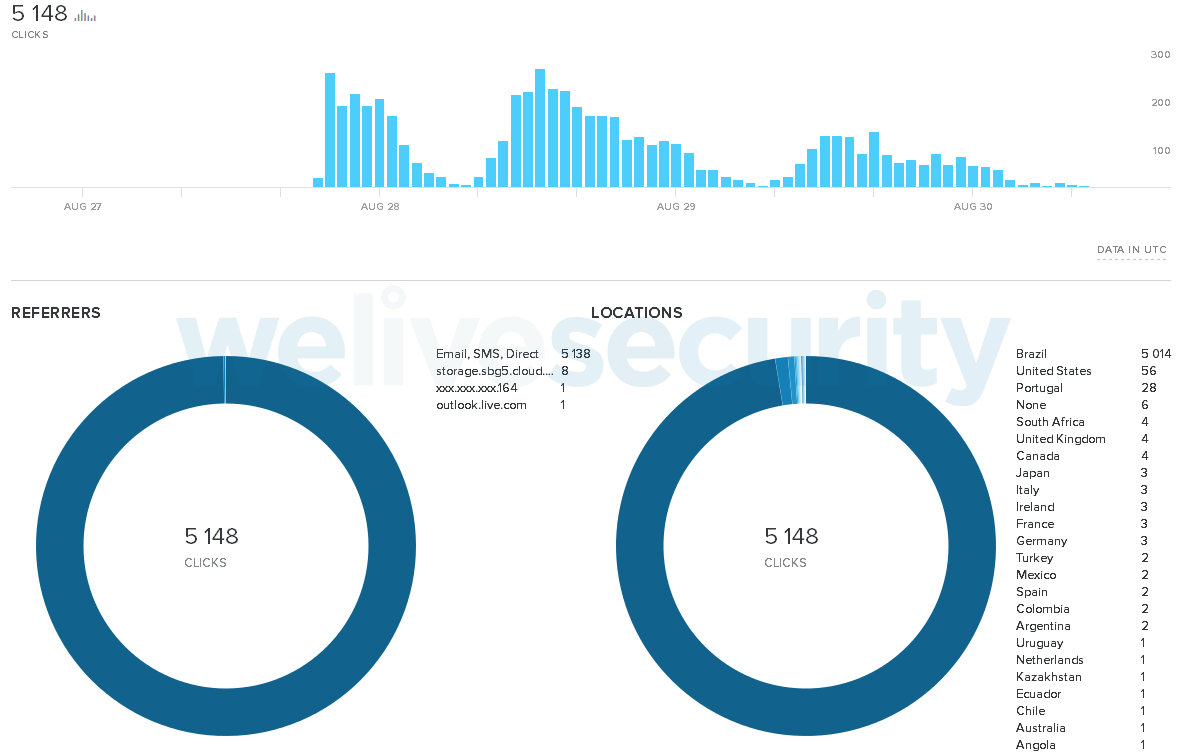

While writing this article, we noticed a new campaign using a similar technique to the one described by enSilo, with only a few changes. The Avast executable is no longer abused and the main payload, jesus.dmp, is no longer encrypted and therefore not associated with an injector. Finally, the installation folder has been changed to %APPDATA%\Sun\Javar\%RANDOM%\. Since this most recent Casbaneiro campaign uses the bit.ly URL shortener, we can learn more about it from Figure 9.

Figure 9. bit.ly statistics for the latest Casbaneiro campaign

Besides that, we identified two other, earlier campaigns during our research.

Campaign 1: Fishy financial manager update

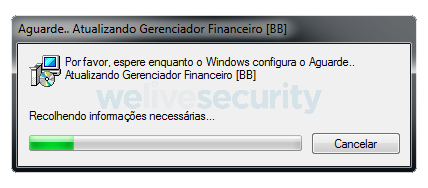

In this campaign, the victim is persuaded to download and install what may seem to be a legitimate update of financial software (see Figure 10). Instead of that, the installer:

- downloads an archive containing:

- Casbaneiro masquerading as Spotify.exe

- other legitimate DLLs

- extracts the content of the archive to %APPDATA%\Spotify\

- sets up persistence using HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run, Spotify = %APPDATA%\Spotify\Spotify.exe

We have also encountered cases where the payload masquerades as OneDrive or WhatsApp. In those cases, the name of the folder is changed accordingly.

Figure 10. Fake update installer. (Translation: Title: Wait.. Updating Financial Manager [BB]. Text: Please wait for Windows configuration to be done.. Updating Financial Manager [BB]. Gathering necessary information.)

Campaign 2: What’s cooking? A fowl Windows activator

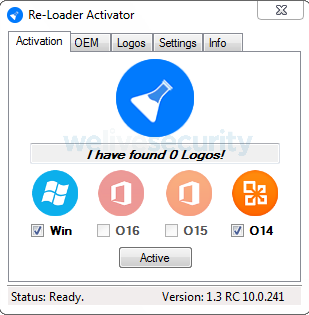

This campaign is very similar to the one described by enSilo; it uses an MSI installer with an embedded JavaScript downloader. Only this time, the installer comes bundled together with the Re‑Loader cracking tool allowing unofficial activation of Windows or Microsoft Office. When executed, Casbaneiro is secretly downloaded and executed first, followed by Re‑Loader.

The attacker used this approach when the expected software is actually installed together with the malware. This method is not very common for Latin American banking trojans. It is more dangerous to the intended victims, because it may give them less reason to suspect anything has gone wrong.

Figure 11. The Re-Loader cracking tool installed together with Casbaneiro

Do you C what I C?

The operators have gone to great lengths to hide the actual C&C server domain and port, and it is one of the most interesting Casbaneiro features. Let’s explore where the C&C servers have been hidden…

1) Stored encrypted in the binary

Encryption is definitely the simplest method to hide the C&C server. The domain is encrypted with a hardcoded key and the port is just hardcoded. We have encountered cases where the port has been stored in the data section, in the Delphi form data, or randomly chosen from a range.

2) Embedded in a document

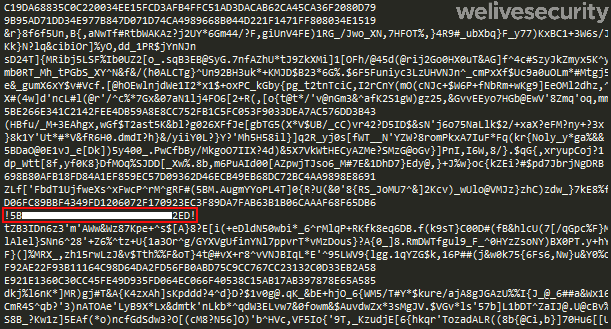

A more advanced method is to store the data somewhere online, in this case on Google Docs. One way Casbaneiro uses this method can be seen in Figure 12, where the document is full of junk text. The encrypted domain is hexadecimal encoded and then stored between “!” delimiters. The encryption used is that used for all other strings, and the port is hardcoded in the binary.

Figure 12. C&C server domain (highlighted red) encrypted and hexadecimal encoded, hidden inside an online document

Another way this method is used involves multiple delimiters. An example can be seen in Figure 13, where different delimiters are used for the C&C port, C&C domain and the URL used to submit victim information. Initially, this method was used to store only the port; the other configuration data were added in later variants.

Figure 13. C&C server port (“thedoor”), domain (“sundski”) and the victim information submission URL (“contict”) encrypted and stored in an online document

3) Embedded in a crafted website

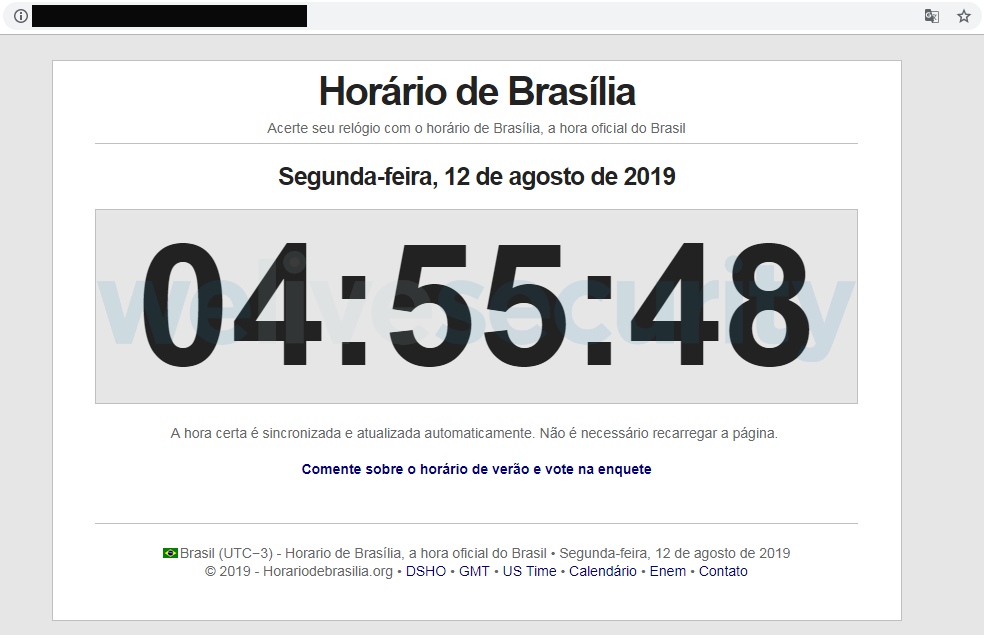

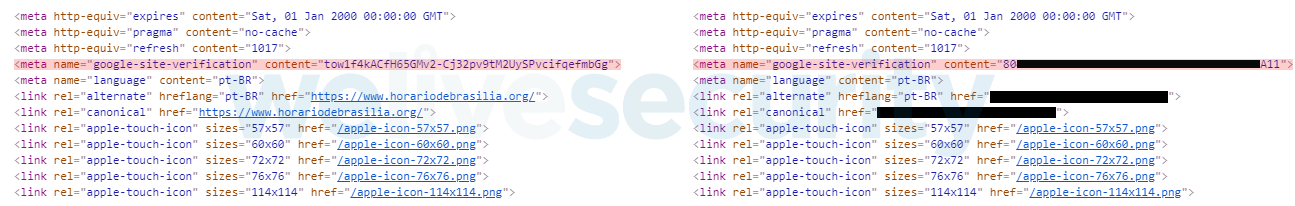

In this approach, the operators set up a fake website (Figure 14) mimicking this legitimate one showing the current time in Brazil. The real C&C domain is hidden inside the web page’s metadata, as can be seen in Figure 15, and the port is hardcoded in the binary. We have encountered at least three such identical websites with different URLs.

Figure 14. Website created by the attacker mimicking a legitimate one. (Partial translation: Brazilian time schedule. Set your watch with time schedule in Brazil, Brazil’s official time.)

Figure 15. Comparison of metadata of the legitimate (left) and fake (right) websites. The google-site-verification tag holds the encrypted C&C domain.

An important difference from the previous method is that the data are encrypted in a different way than all other strings, using the algorithm to decrypt remote configuration data described earlier. The three keys required are the first 12 bytes of the string, each taking 4 bytes.

4) Embedded in a legitimate website

If you have been wondering where the title of this blog post comes from, this section is for you!

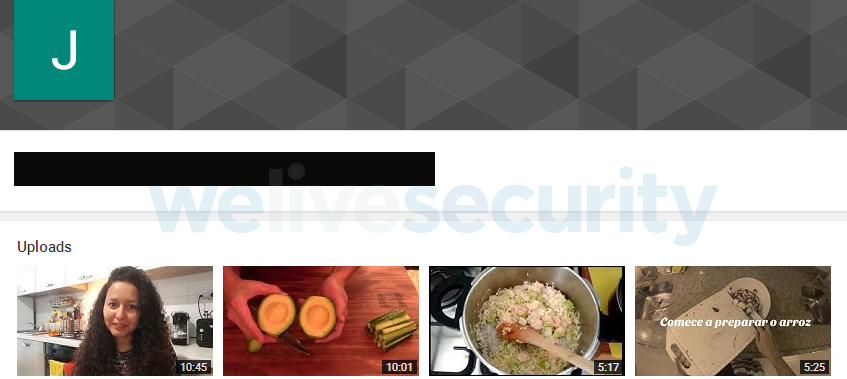

Casbaneiro started to abuse YouTube to store its C&C server domains. We have identified two different accounts used for this by the threat actor – one focused on cooking recipes and the other one on soccer.

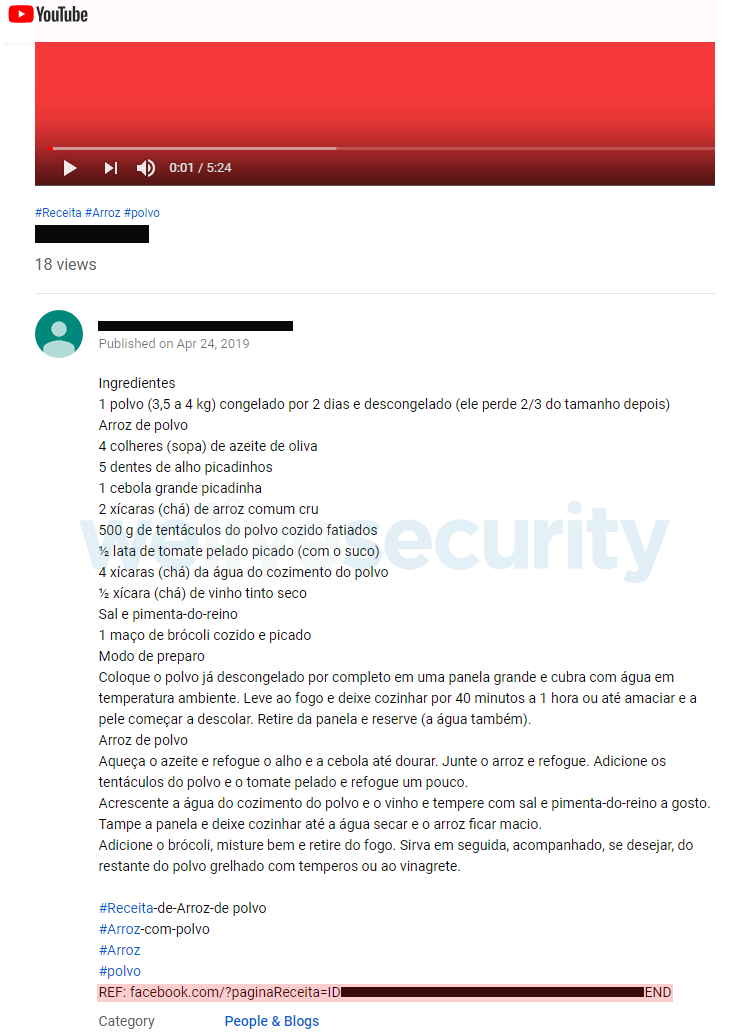

So where is the C&C server hidden? Each video on these channels contains a description. At the end of this description, there is a link to a bogus Facebook or Instagram URL (see Figure 17). The C&C server domain is stored in this link, using the same encryption scheme as in the previous case – the key is stored at the beginning of the encrypted data. The port is, once again, hardcoded in the binary.

Figure 16. One of the YouTube channels used by the attacker

Figure 17. Description of one of the videos the attacker posted. At the bottom, the encrypted C&C domain is embedded in a bogus Facebook link (red).

What makes this technique dangerous is that it does not raise much suspicion without context. Connecting to YouTube is not considered unusual and even if the video is examined, the link at the end of the video description may easily go unnoticed.

5) Generated using a fake DNS entry

The general idea of this method is to register a domain and associate it with a fake IP address so that the real IP address can be derived from it. The algorithm uses three input values:

- A base domain (B) - a domain used to derive other domains

- A list of suffixes (LS) - a list of strings that will be used to derive other domains from the base domain B

- A number (N) - a number used to transform a fake IP address to the real one

A different base domain is used for C&C domain and port. We provide pseudocode in Figure 18. The basic logic of the algorithm is:

- Generate a domain from the base domain B and resolve it to a fake IP address (FIP)

- Add a number N to the fake IP address FIP to get the real IP address

- To get the port, sum the octets of the real IP address and multiply by 7

def get_real_ip(base_domain, suffix, n):

items = base_domain.split(".", 1)

items[0] += suffix

generated_domain = '.'.join(items)

if is_registered(generated_domain):

fake_ip = resolve(generated_domain)

return fake_ip + n

else:

return 0

def get_real_domain(base_domain, strings_list, n):

# First, try to resolve the base domain without suffix

real_ip = get_real_ip(base_domain, "", n)

if not real_ip:

# If that fails, try the suffixes one by one

for suffix in string_list:

real_ip = get_real_ip(base_domain, suffix, n)

if real_ip:

break

return real_ip

def get_real_port(base_domain, strings_list, n):

# Do all the steps as when getting the domain

ip = get_real_domain(base_domain, strings_list, n)

# Get the octets of the ip, sum them and multiply by 7

octets = str(ip).split('.')

return sum(octets) * 7Figure 18. Pseudocode of the algorithm used to generate C&C domain and port using a fake DNS entry

Download & Execute functionality

Most of the Latin American banking trojans, including Casbaneiro, have a way to download and execute other executables, usually via a backdoor command. However, Casbaneiro employs a different implementation of this functionality. We initially thought of it as an update mechanism because newer versions of the banking trojan were distributed by it but, as we found out later, not exclusively. Two different mechanisms are used; let’s explore them.

Via XML document

One way that this functionality is used is by downloading an XML document. Data stored in this document between the <xmlUpdate>## and ##</xmlUpdate> labels are encrypted using the algorithm for remote data provided in Figure 8.

Once decrypted, the data may contain the following tags:

- <newdns> – new C&C server domain

- <newport> – new C&C server port

- <downexec> – a URL to use to download and execute a file

Via special configuration file

We believe this approach is used in (probably a subset of) Casbaneiro samples that are being sold to other cybercriminals. In this method, a configuration file is downloaded (as shown in Figure 19). It consists of multiple lines, each one containing:

- An ID of the buyer

- Payload archive filename

- Main URL where the archive is located

- Backup URL where the archive is located

- Version (not used)

- A number (not used)

- Date (not used)

The latter three values seem to be ignored completely. The date “07/05/2018”, for example, is used even in the newest configuration files at the time of writing.

Figure 19. Configuration file obtained by Casbaneiro

Each Casbaneiro sample using this method has the buyer’s ID hardcoded in its data. When it downloads such configuration file, it parses it and finds the line that is intended for the specific buyer’s ID and downloads and executes the payload.

As you can see in Figure 19, the payload is mostly the same for all the buyers. However, we have encountered a situation where a sample downloaded such a configuration file and its buyer’s ID was not present. This way of distributing additional payloads gives the “main author” (probably the seller) the ability to exclude some buyers.

Besides Casbaneiro updates, we have seen two more payloads being distributed by this method, which are covered in the next two sections.

Email tool

A tool written in C# automatically registers a large number of new email accounts using the Brasil Online (BOL) email platform and sends the credentials back to the attacker. If you have read our previous article, this may seem very familiar to you. That is because, as far as functionality goes, this tool does exactly the same thing. It is also a variant of the spam tool described by Cisco.

Password stealer

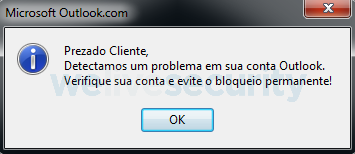

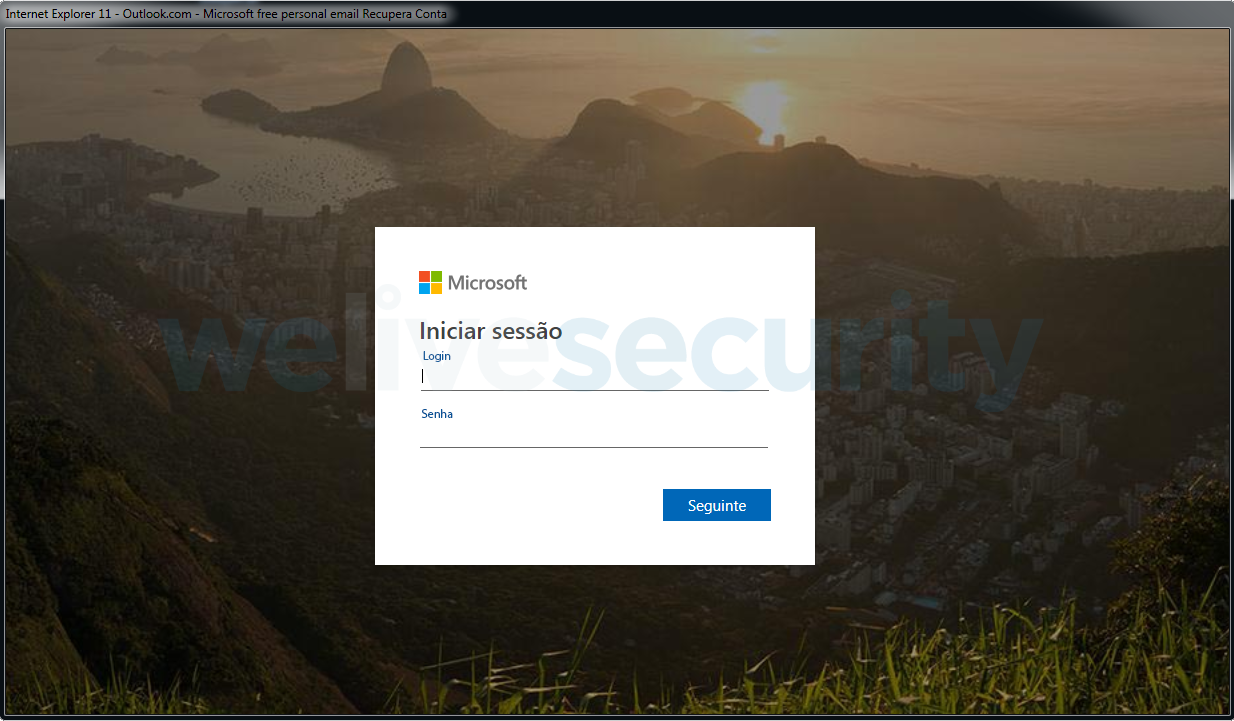

Another payload we have seen being distributed by this functionality is a very simple Outlook password stealer. This malware, once executed, first displays a message box stating, in Portuguese, there is an issue with the victim’s Outlook account. After that, it displays a fake Microsoft login page requesting Outlook credentials.

Figure 20. Message box displayed by the password stealer. (Translation: Dear client, we have detected a problem with your Outlook account. Please check your account and avoid permanent blockage!)

Figure 21. Window displayed by the password stealer that tries to obtain the victim's Outlook credentials. (Translation: Microsoft free personal email recover account. Begin session. Login, Password. Next)

Conclusion

In this article, we talked about Casbaneiro, another Latin American banking trojan. We have shown that it shares the common characteristics for this type of malware, such as using fake pop-up windows and containing backdoor functionality. In some campaigns, it splits its functionality into an injector and the actual banking trojan. It also masquerades as a legitimate application in most of the campaigns and targets Brazil and Mexico.

We have also shown strong indicators leading us to believe that Casbaneiro is closely related to Amavaldo. Both pieces of malware use the same, uncommon cryptographic algorithm in the injector component, they have used a very similar PowerShell script in one of their campaigns and they have been seen distributing a very similar email tool.

We have described various techniques Casbaneiro employs in order to hide its C&C server address. These include using remotely stored documents, both legitimate and fake websites and fake DNS entries.

Finally, we have described two techniques used by Casbaneiro to update itself or download and execute additional payloads.

For any inquiries, contact us as threatintel@eset.com. Indicators of Compromise can also be found on our GitHub.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

Hashes

Campaign 1: Fishy financial manager update

| SHA-1 | Description | ESET detection name |

|---|---|---|

| F07932D8A36F3E36F2552DADEDAD3E22EFA7AAE1 | MSI installer | Win32/TrojanDownloader.Banload.YJD trojan |

| BCDF0DDF98E3AA7D5C67063B9926C5D1C0CA6F3A | Downloaded payload | Win32/Spy.Casbaneiro.AJ trojan |

Campaign 2: What’s cooking? A fowl Windows activator

| SHA-1 | Description | ESET detection name |

|---|---|---|

| 8745197972071EDE08AA9F7FBEC029BED56151C2 | MSI installer | JS/TrojanDownloader.Agent.TNX trojan |

| BC909B76858402B3CBB5EFD6858FD5954A5E3FD8 | Re-Loader | MSIL/HackTool.WinActivator.J potentially unsafe application |

Campaign 3: The most recent one

| SHA-1 | Description | ESET detection name |

|---|---|---|

| DD2799C10954293C8E7D75CD4BE2686ADD9AC2D4 | MSI installer | JS/TrojanDownloader.Agent.TNX trojan |

| 9DFFEB147D89ED58C98252B54C07FAE7D5F9FEA7 | Downloaded payload | Win32/Spy.Casbaneiro.AJ trojan |

Files distributed by Download & Execute

| SHA-1 | Description | ESET detection name |

|---|---|---|

| C873ED94E582D24FAAE6403A17BF2DF497BE04EB | Email tool | MSIL/SpamTool.Agent.O trojan |

| B3630A866802D6F3C1FA2EC487A6795A21833418 | Password stealer | Win32/PSW.Agent.OGH trojan |

Filenames

- %APPDATA%\Spotify\Spotify.exe

- %APPDATA%\OneDrive\OneDrive.exe

- %APPDATA%\WhatsApp\WhatsApp.exe

- %APPDATA%\Sun\Javar\%RANDOM%\%RANDOM%.exe

- %APPDATA%\DMCache\%RANDOM%\%RANDOM%.exe

Run key & values

- HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

- Spotify = %APPDATA%\Spotify\Spotify.exe

- OneDrive = %APPDATA%\OneDrive\OneDrive.exe

- WhatsApp = %APPDATA%\WhatsApp\WhatsApp.exe

- %Random% = %APPDATA%\Sun\Javar\%RANDOM%\%RANDOM%.exe

- %Random% = %APPDATA%\DMCache\%RANDOM%\%RANDOM%.exe

C&C servers

- hostsize.sytes[.]net:7880

- agosto2019.servepics[.]com:2456

- noturnis.zapto[.]org

- 4d9p5678.myvnc[.]com

- seradessavez.ddns[.]net:14875

Bitcoin wallet

- 18sn7w8ktbBNgsX8LeeeLMqKS84xMG54si

MITRE ATT&CK techniques

| Tactic | ID | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Access | T1192 | Spearphishing Link | Some Casbaneiro campaigns start with a malicious link in an email. |

| T1193 | Spearphishing Attachment | Some Casbaneiro campaigns start with a malicious email attachment. | |

| Execution | T1073 | DLL Side-Loading | Some campaigns bundle a legitimate executable so as to use this technique in order to execute Casbaneiro. |

| T1086 | PowerShell | One distribution chain uses an obfuscated PowerShell script. | |

| Persistence | T1060 | Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder | Casbaneiro downloaders set up persistence via Run key. |

| Defense Evasion | T1140 | Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information | Casbaneiro uses encrypted remote configuration data and its commands are encrypted too. |

| T1036 | Masquerading | Casbaneiro sometimes masquerades as or is bundled with a legitimate application. | |

| T1064 | Scripting | PowerShell and JavaScript are used in Casbaneiro distribution chains. | |

| Credential Access | T1056 | Input Capture | Casbaneiro contains a command to execute a keylogger. It also steals contents from fake windows it displays. |

| Discovery | T1083 | File and Directory Discovery | Casbaneiro searches for various filesystem paths in order to determine what applications are installed on the victim's machine. |

| T1057 | Process Discovery | Casbaneiro searches for various process names in order to determine what applications are running on the victim's machine. | |

| T1063 | Security Software Discovery | Casbaneiro scans the system for installed security software. | |

| T1082 | System Information Discovery | Casbaneiro extracts the version of the operating system. | |

| Collection | T1115 | Clipboard Data | Casbaneiro captures and replaces bitcoin wallets in clipboard. |

| T1113 | Screen Capture | Casbaneiro contains a command to take screenshots. | |

| Command and Control | T1024 | Custom Cryptographic Protocol | Casbaneiro uses three different custom cryptographic protocols. |

| T1032 | Standard Cryptographic Protocol | Casbaneiro encrypts its commands using the standard AES protocol. | |

| Exfiltration | T1041 | Exfiltration Over Command and Control Channel | Casbaneiro sends the data it collects to its C&C server. |