According to an article by the BBC, the United Kingdom’s Digital Minister Margot James is proposing legislation to introduce a new labelling system to show customers how secure an IoT product is.

In order to gain the necessary label, IoT devices will need to:

- by default have a unique password,

- state clearly for how long security updates will be made available,

- offer a public point of contact for vulnerability disclosure.

The initiative, which is part of the UK’s bid to be a global leader in online safety, follows California’s legislation that comes into effect in 2020 and bans weak passwords on internet-connected devices. Both the proposed UK and actual Californian legislation are steps in the right direction, or at the very least will make vendors consider security at the design phase of developing an IoT product. But is legislation the answer?

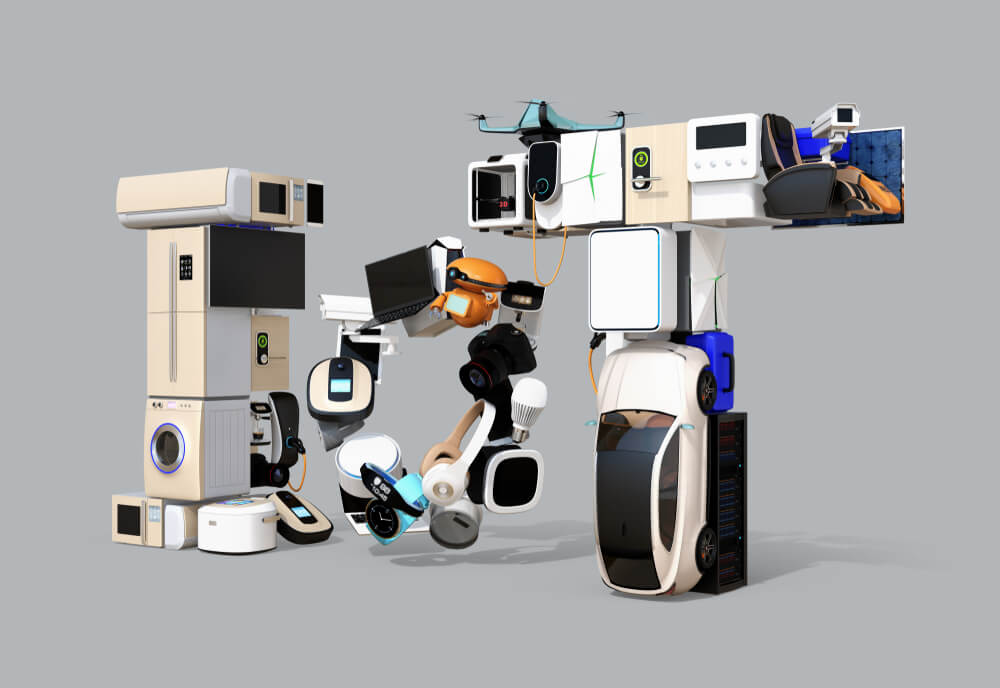

Let us now pause to consider what is actually meant by IoT devices here. The Californian law offers the following definition: a connected device “means any device, or other physical object that is capable of connecting to the Internet, directly or indirectly, and that is assigned an Internet Protocol address or Bluetooth address”. This covers a wide variety of devices, cars, light bulbs, laptops, thermostats to cell phones, the list is endless.

On my desk I have a Bluetooth speaker. It has no password, it gathers no data, nor transmits any, or at least to my knowledge. Is this device covered by the Californian legislation? Will it need a unique password?

In the same vein, should a consumer purchasing a Tesla car in the UK expect to see a label on the car stating that it meets the basic security legislation for IoT? Or does every device within the Tesla that may communicate independently need to have a label?

So insecure

The need for security is without question, and some, maybe many, of the manufacturers of IoT devices have failed to take reasonable measures to secure their devices. And it’s this failing that has driven politicians to act. In the UK this started with a voluntary code of practice, and it is a subset of this that is now progressing towards legislation.

But as a general rule, legislation stifles innovation. The technology industry is already moving away from passwords. Bret Arsenault, Microsoft’s Chief Information Security Officer, announced that 90 percent of Microsoft employees can log on to the corporate network without a password, as the company envisages a ‘world without passwords’. Its employees are using other options, including Windows Hello and the Authenticator app, that provide alternatives such as facial recognition, fingerprints, and two-factor-authentication.

Legislation that is not effective until next year or is still being proposed is likely to be out of date by the time it takes full effect. It will compel device manufacturers to use technology that an industry is attempting to move away from in search of more secure options.

In a recent analysis of data that has been subject to breach, the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) found that 23.2 million user account worldwide were secured with ‘123456’, and 7.7 million used ‘123456789’ as password. The data demonstrates a lack of engagement by consumers to secure their online accounts, a complacency that creates opportunity for cybercriminals.

I recently presented at cybersecurity events both in the USA and Argentina on the need to consider security when connecting any device to a network, specifically in smart buildings. A question to the audience – “when did you last update the infotainment system in your car?” –had the same results in both places. The audience looked perplexed. They are cybersecurity experts and yet they connect their phone, a very personal device, by Bluetooth to a system they never update. Amusingly, one attendee connected with me the following day and said that neither he nor the dealer could update his system despite it being out of date.

Fast forward a few years, and you get the shiny new IoT device home, with its label showing that is has a unique password and there will be updates for five years. On first use, and for simplicity, you set the password to the same as all the other passwords on devices in the house, you plug the device in and enjoy the convenience of whatever functionality it comes with. When the manufacturer sends you an email notification that there is a firmware update, assuming you registered the device, you delete it as the device is working and why update something that works.

While legislation drives industry to make devices more secure out of the box it is likely to be education and engagement of consumers that will make them more secure in their home. I wonder if you can legislate for this?