As employees of ESET, we have many discussions on WeLiveSecurity revolving around malicious software and hardware threats, and the tools to counter them. However, security is a much broader category than just that, and it includes both the availability of and the integrity of your information, and a part of that is physical protection. These days, the latest risks we often hear about are things like breaches of data stored in the cloud, or compromised IoT devices. However, it is important to remember that these sorts of risks are in addition to—not instead of—other older and less "sexy" risks, such as hard drive crashes.

INTRODUCTION

On the r/sysadmin section of Reddit, I recently participated in a discussion about hard disk drive failures from smoke, which forms the basis for this article. Since this is not a topic we normally cover on WeLiveSecurity, a little bit of background may be helpful.

Image 1: Inside view of a hard disk. SPBer - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Conventional hard disk drives work by spinning a series of aluminum or glass platters on a spindle driven by an electric motor. And when spun up, they are going pretty fast and with incredibly fine tolerances: hard disk drives used in servers spin their platters at up to 15,000 revolutions per minute (RPM), which works out to around 150 mph (or about 240 kph, for the metrically minded). Just barely above and below these platters float minuscule read-write heads, each less than a millimeter wide, at the end of an actuator arm. How far apart do the actuator arms place the heads from the platters? As little as 3 nanometers, or about 1/25,000th the thickness of a human hair. Read-write heads themselves are so small that they are manufactured using similar technologies to those used to make CPUs. All of these parts come together in a device that looks not too different from a record player, aside from its size.

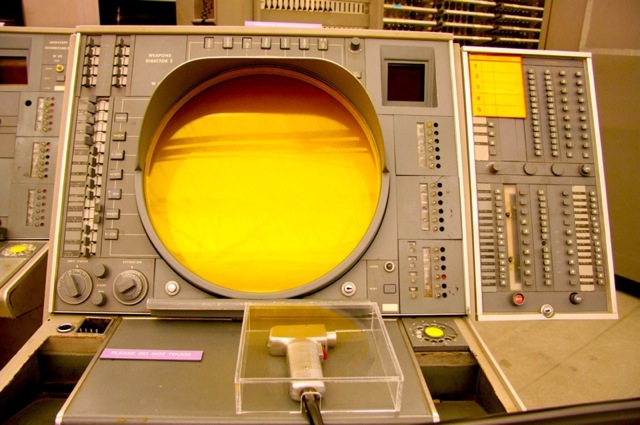

At the dawn of the hard disk drive era, the distance between the read-write heads and the platters inside the hard drive enclosure was much greater, so much so that smoke particles, often less than a micron in size, might pass between the platters and read-write heads with ease. One can imagine that mainframe computers with high-pressure-air- or water-cooling systems in a computer center would have air filtering systems similar to a clean room, with air filters serviced regularly according to a schedule. For that matter: SAGE, one of the earliest distributed military computer systems, had built-in cigarette lighters and ashtrays.

Image: SAGE console. gizmodo.com

One of the interesting things about the conventional-type hard disk drives that go into desktop and laptop computers is that they have altitude specifications both for use and just for being transported. This is because they are not actually sealed assemblies, as one might think, but have an air pressure equalization hole on them somewhere (usually with a 'do not cover' sticker next to it) that allows the pressure of the air inside the hard disk drive to remain the same as the air pressure outside of it. This helps ensure that your hard disk drive doesn't crush itself or pop open due to changes in altitude. Why does all this matter? A hard disk drive's read-write heads rely on the Bernoulli effect to float above the drive's platters, and as air pressure decreases, the read/write heads begin to float closer to the platters.

SMOKE DAMAGE

Where do smoke particles fit into all of this? Well, hopefully they do not, because smoke particles are some of the most damaging things that can get inside a hard disk drive. Under a microscope they often look like jagged rocks, and some of them are small enough that they can actually can get drawn in through the air pressure equalization hole and end up bouncing across the surface of the platter at high speed, causing microscopic scratches and flaking of the thin film material on the surface of the platters, which is where data is actually stored. Even with filters inside the drive assembly, the particles can still cause damage: One can imagine them impacting the read-write heads flying just a few nanometers from the surface of the platters, much like a bird or drone hitting an airplane. Not a great experience for the passengers or your data.

As it turns out, not all hard disk drives are open to the air. Over the past few years, the highest-capacity enterprise hard disk drives are filled with an inert gas, such as helium, during manufacturing and then hermetically sealed. This allows the platters and read-write head assemblies to be placed even closer to each other, while moving faster, and being quieter, all while consuming less electricity. Originally pioneered by Hitachi (whose storage division is now owned by Western Digital), the technology is also used by other hard disk drive manufacturers such as Seagate and Toshiba. And while smoke particles may not be able to work their way inside these types of sealed hard disk drives, it is important to remember that they can be corrosive (depending upon their source) and that they can still cause oxidation damage to the exposed parts of a hard disk drive, such as the drive controller's circuit board.

RECOVERY

If a hard disk drive has been exposed to water or fire, the damage is usually quite obvious. When the exposure is only to smoke there may be no obvious signs of damage. Also, the damage may not occur immediately, but take weeks or months to manifest, often in subtle and difficult to determine ways.

If a hard disk drive has been exposed to smoke, then the first thing you would want to do with it is power down the system, discharge static by grounding yourself and the computer, remove the hard disk drive, and clean the exterior with an antistatic, lint-free, microfiber cloth. For the circuit board, an anti-static nylon brush used for cleaning the inside of computers works well. If there's a visible layer of smoke residue on the hard disk drive, very gently cover the air pressure equalization hole with a piece of electrical tape (cutting a small piece of tape and sticking it 'upside-down' to the adhesive side creates a non-sticky zone over the hole), then moisten the cleaning cloth or brush in a 1:1 mixture of distilled water and isopropyl alcohol so that it is damp (not soaking wet, but damp) and clean the exterior. Do not remove the electrical tape until the hard disk drive is completely dry. Once it is dry, gently remove the tape and very lightly clean around the air pressure equalization hole with a dry cloth in a direction away from the hole. Under no circumstances should the hard disk drive be powered on while the air pressure equalization hole is covered.

After the hard disk drive's exterior surface is cleaned, dried and the tape removed, it can be plugged into a computer, and any valuable data can be copied from it.

At this point, you are pretty much done, at least regarding moving the data to a safer location.

The hard disk drive may still be serviceable, especially if it was powered down at the time it was exposed to smoke and cleaned afterward. Running the hard disk drive manufacturer's diagnostic program can help determine if a hard disk drive can be returned to use. Seagate Technology (including Maxtor) drives can be checked with SeaTools, and Western Digital (including Hitachi) drives can be checked with Data LifeGuard Diagnostic. Even so: depending on your needs, you may want to consider replacing the drive and using it only for non-critical data storage, if at all. There are also diagnostic programs available from third parties that can check a hard disk drive for errors.

If a hard disk drive is severely damaged from smoke, fire or water, contact a professional data recovery service instead of attempting to recover data, as any attempt at recovery on your own part may lead to the data being completely and permanently irretrievable.

CONCLUSION

It is important to remember that the failure rate for all hard disk drives is 100%... eventually. There are, however, steps one can take to improve the chances of having access to your data for a long time:

- The first is to make regular backups of any important information stored on your computer. Several years ago I wrote a paper on backup basics that reviews the various technologies you can use to keep a copy of your data safer.

- The second is a HOWTO I wrote for the Spiceworks IT community about taking care of external hard disk drives. External hard disk drives are convenient for backups, but because they are small, portable devices, they also need some additional safeguards.

While neither of these relates directly to it, they may help you prevent or at least reduce your costs in the event of smoke damage.

Special thanks to my ESET colleagues Bruce P. Burrell, Shane Curtis, Nick FitzGerald and Fer O'Neill for their assistance with this article.