The cybercrime industry cost the world three trillion dollars in 2015 and it is predicted that this amount will rise to six trillion by 2021, according to this 2018 Cybersecurity Ventures post. When we say cost, we are talking about all the expenses incurred in the aftermath of an incident. In a ransomware attack, for example, it is not only the payment of the ransom that counts, but also all the costs of the subsequent loss of productivity, improvements to security policies, investments in technology, and damage to the company's image, just to name a few.

Of course, we know that cybercrime as a service is nothing new. The criminals offer their products or infrastructure on the black market for a price. But what do they offer and how much does it cost? We spent some time browsing the dark web to find the answers to these questions.

Ransomware as a service

A wide range of ransomware packages are on sale on the dark web, just as if it were the sale of legal software. Updates, technical support, access to C&C servers, and a range of payment plans are some of the features on offer.

Image 1: Ranion ransomware is available on the dark web

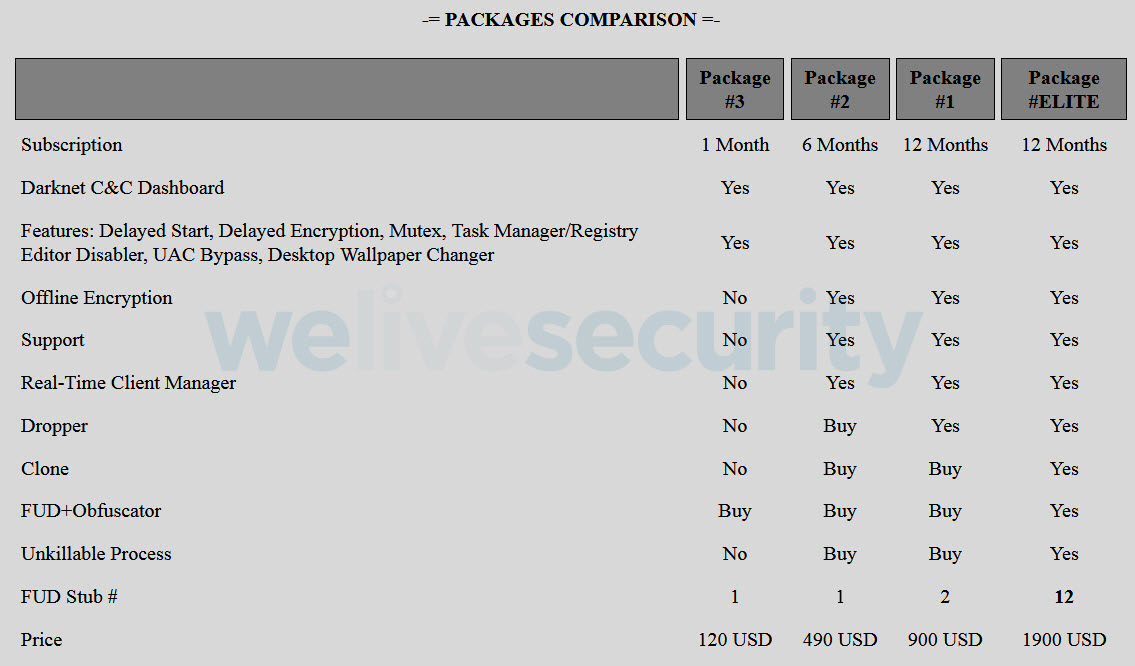

One of the ransomware packages offered is Ranion, whose payment model is based on monthly and yearly subscriptions. There are various subscription plans available at different prices, the cheapest being US$120 for just a month and the most expensive being US$900 for a year, which can rise to US$1900 if you add other features to the ransomware executable.

Image 2: Subscription plans offered by cybercriminals for Ranion ransomware

Another payment model that cybercriminals use to sell their ransomware is to offer the malware and C&C infrastructure free of charge initially, but then take a cut of any payments received from the victims.

Whichever strategy is used, we can see that anyone who wants to be contracted for these services would also need to take care of propagating the malware. In other words, they would need to get the ransomware to their victims, for example, running spam email campaigns or by accessing vulnerable servers via RDP.

Selling access to servers

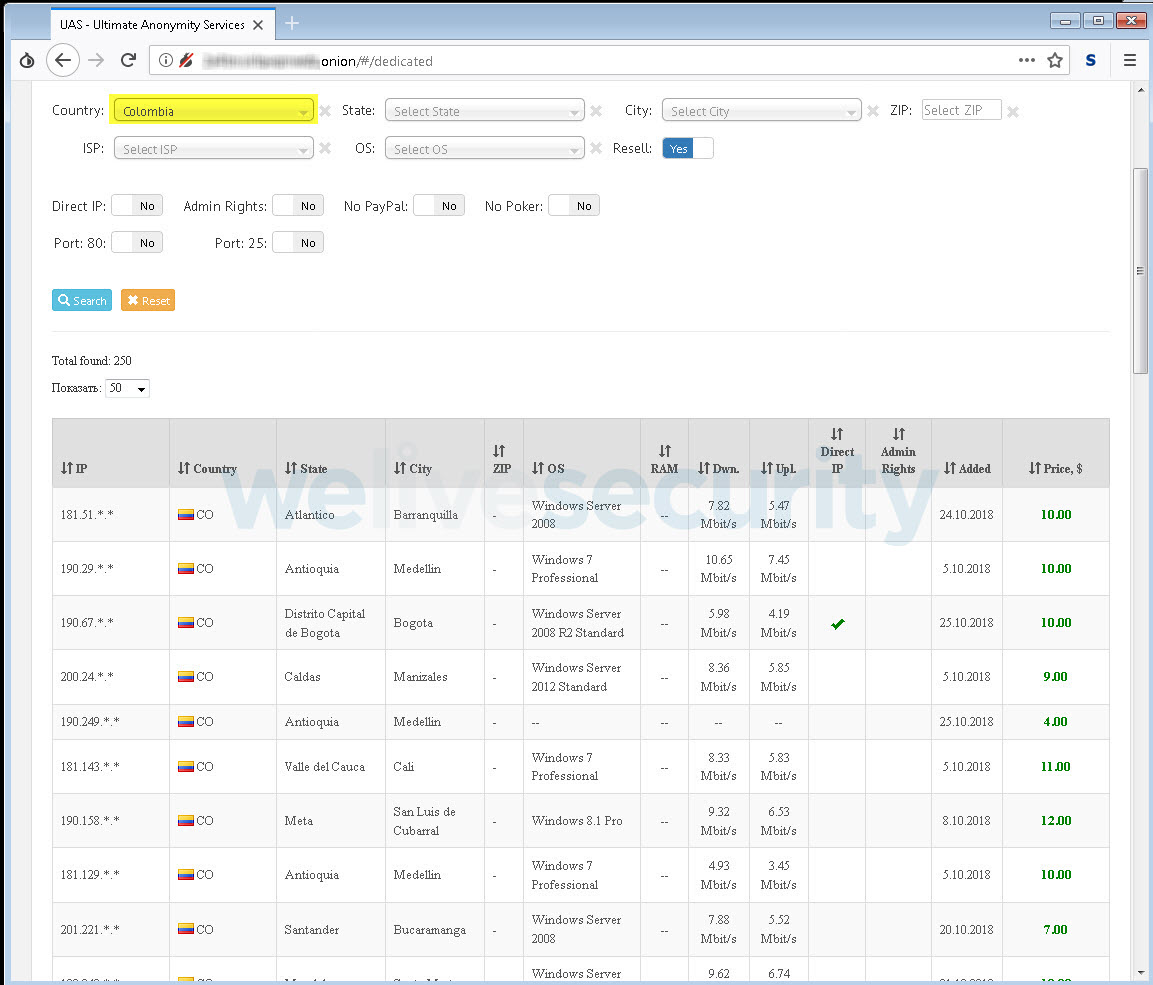

There are various services on the dark web offering credentials that give access to servers in various parts of the world via remote desktop protocol (RDP). The prices are in the range of US$8-15 per server and you can search by country, by operating system, and even by which payment sites users have accessed from that server.

Image 3 – Selling access via RDP to servers in Colombia

In the image above, we can see how filtering has been used to show only servers located in Colombia, and that there are 250 servers available. For each server, certain details are provided, which can be seen in the next image.

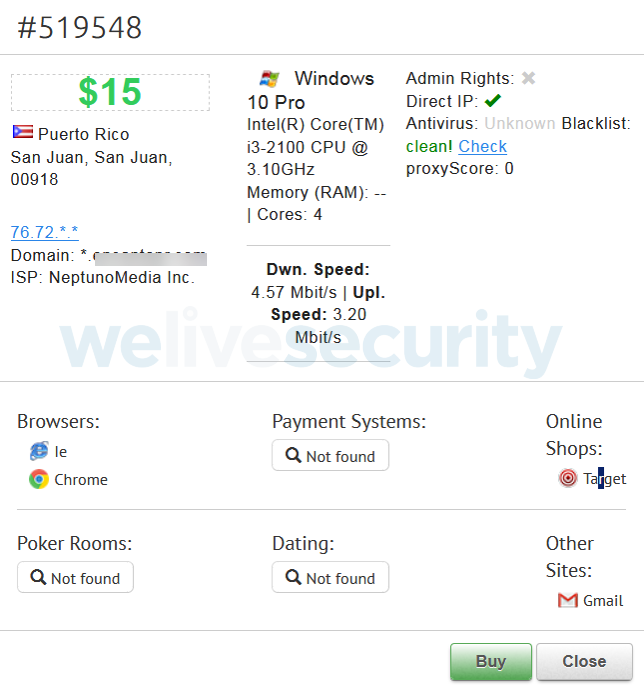

Image 4: Detailed information about server access offered on the dark web

After buying such access, a cybercriminal might then use it to run ransomware or perhaps to install more discreet malware, such as banking Trojans or spyware.

Renting infrastructure

Some criminals who have developed botnets, or networks of compromised computers, rent out their computing power to be used for sending spam emails or for launching DDoS attacks.

For denial of service attacks, the price varies depending on how long the attack is to last (ranging from 1 to 24 hours) and how much traffic the botnet is capable of generating during that time. The image below shows an example of US$60 for three hours.

Image 5: Example of a cybercriminal offering to rent out their infrastructure to run DDoS attacks

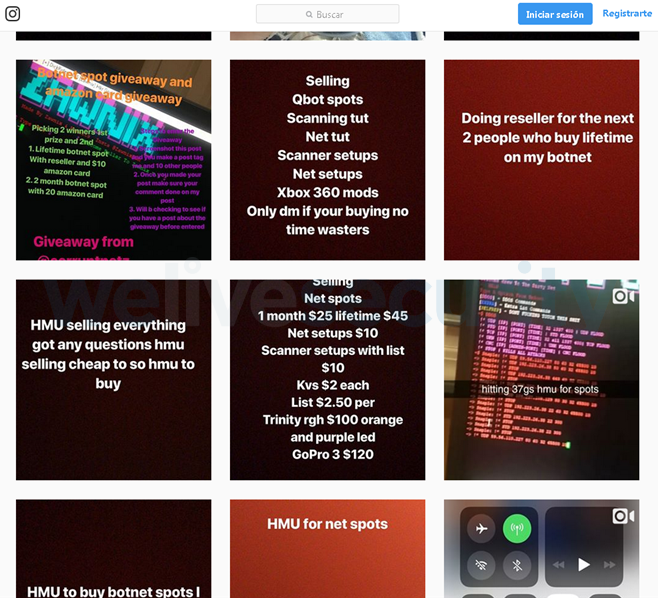

You can even see young teens and adults offering to rent out their (small) botnets, mostly to attack servers used by online games like Fortnite. They use social networks to promote themselves and they do not seem particularly concerned about staying anonymous. Often, they also offer to sell stolen accounts.

Image 6 – Instagram being used as a platform to offer botnets for rent

Image 7 – YouTube users show DDoS attacks on Fortnite servers

Selling PayPal and credit card accounts

Cybercriminals who run successful phishing attacks do not usually take the risk of using the stolen accounts themselves. It is already profitable enough and much safer for them to resell the accounts to other criminals. As we see in the next image, they generally charge about 10% of the total credit available in the stolen account.

Image 8 – Selling PayPal and credit card accounts

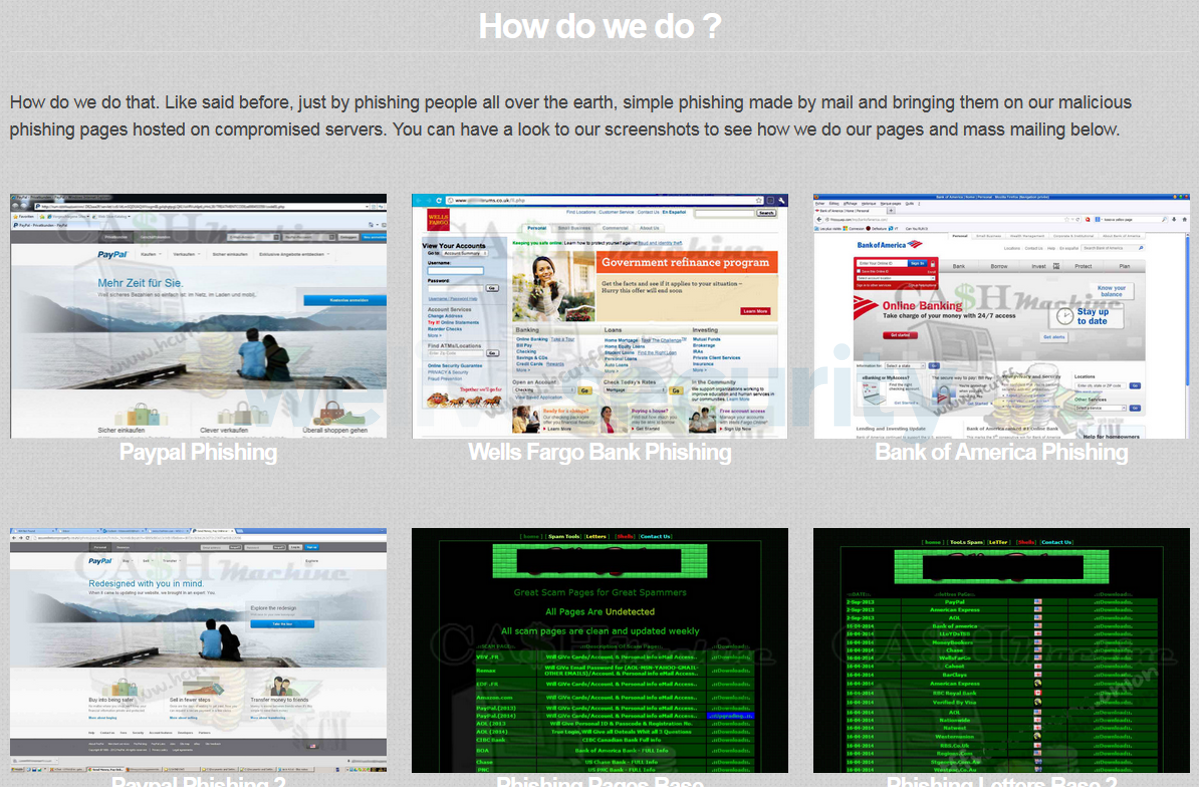

Some sellers are even happy to show the tools and fake sites they use to operate their phishing activity.

Image 9 – Cybercriminals explain things step by step

So, we can see that cybercriminals, hidden by tools that give them a certain degree of anonymity, have put together a profitable criminal industry, which includes everything from advertising and marketing to customer service, updates, and user manuals. It is worth noting, however, that within this criminal ecosystem there are a lot of internal customers, and the real profit is made by the big fish that already have a well-established infrastructure or service.

As ESET’s Global Security Evangelist Tony Anscombe mentioned during his presentation at Segurinfo 2018, “The malware industry has stopped being disruptive and now has characteristics similar to those of a software company.” This means the software, products, and services offered by cybercriminals in this industry now benefit from established processes for sales, marketing, and distribution.