SSH, short for Secure SHell, is a network protocol to connect computers and devices remotely over an encrypted network link. It is generally used to manage Linux servers using a text-mode console. SSH is the most common way for system administrators to manage virtual, cloud, or dedicated, rented Linux servers.

The de facto implementation, bundled in almost all Linux distributions, is the portable version of OpenSSH. A popular method used by attackers to maintain persistence on compromised Linux servers is to backdoor the OpenSSH server and client already installed. There are several reasons why creating malware based on OpenSSH is popular:

- It doesn’t require a new TCP port to be opened on the compromised machine. SSH should already be there and likely reachable from the internet.

- The OpenSSH daemon and client see passwords in clear text, providing the attacker the potential to steal credentials.

- OpenSSH source code is freely available, making it easy to create a "customized" (backdoored) version.

- OpenSSH is built to make it difficult to implement a man-in-the-middle attack and snoop on its users’ activity. Attackers can leverage this to stay under the radar while they conduct their malicious activities on the compromised server.

To better combat Linux malware threats, ESET researchers went on the hunt for in-the-wild OpenSSH backdoors, both known and unknown. We started our investigation on knowledge gleaned from one of our previous research efforts, Operation Windigo. In that white paper, we described in detail Windigo’s multiple malware components and how they work together. At its core was Ebury, an OpenSSH backdoor and credential stealer that was installed on tens of thousands of compromised Linux servers worldwide.

Something that wasn’t originally discussed in the Operation Windigo paper, but that ESET researchers have talked about at conferences, is how those attackers try to detect other OpenSSH backdoors prior to deploying their own (Ebury). They use a Perl script they have developed that contains more than 40 signatures for different backdoors.

@sd = gs( 'IN: %s@ \(%s\) ', '-B 2' );

@sc = gc( 'OUT=> %s@%s \(%s\)', '-B 1' );

if ( $sd[1] =~ m|^/| or $sc[0] =~ m|^/| ) {

print

"mod_sshd29: '$sd[0]':'$sd[1]':'$sd[2]'\nmod_sshc29: '$sc[0]':'$sc[1]'\n";

ssh_ls( $sd[1], $sc[0] );

}

Example signature found in Windigo Perl script to detect OpenSSH backdoor (tidied output)

When we looked into these signatures, we quickly realized that we did not have samples matching most of the backdoors described in the script. The malware operators actually had more knowledge and visibility into in-the-wild SSH backdoors than we did. To cope with this situation, we started hunting for the missing malware samples using their signatures. This helped us to find samples previously unknown to the computer security industry and to report detailed research findings.

Today, ESET researchers are publishing a paper focused on 21 in-the-wild OpenSSH malware families. While some of these backdoors have already been analyzed and documented online, no analysis of most of them was available until now. The intent of this paper is to provide an overview of the current OpenSSH backdoor landscape. It is the result of a long-term research project involving writing rules and detections, deploying custom honeypots, classification of samples, and analysis of the different malware families.

Unveiling the dark side

Soon after the Windigo research, we translated the signatures from the aforementioned Perl script into YARA rules (now available on GitHub) and used them to find likely new malware samples from our various feeds. We collected new samples for more than three years and, after filtering out false positives, obtained a few hundred trojanized OpenSSH binaries. The analysis of this collection highlights the use of a set of common features across the different backdoors. Two of them really stand out:

- 18 out of the 21 families feature a credential-stealing feature, making it possible to steal passwords and/or keys used by the trojanized OpenSSH client and server.

- 17 out of the 21 families feature a backdoor mode, allowing the attacker a stealthy and persistent way to connect back to the compromised machine.

More details about the common features of these OpenSSH backdoors are provided in the white paper.

In parallel with the analysis of the collected samples, we set up a custom honeypot architecture (detailed in-depth in the white paper) to extend our results. The idea was to provide (i.e. intentionally leak) credentials to the attackers using exfiltration techniques reverse-engineered from the samples. This would allow us to observe the behavior of the attackers once they compromise a server, and hopefully get the most recent samples.

Combining our passive hunting with the YARA ruleset and the interaction of attackers with our honeypot gives us insight into both how active the attackers are and what their skillsets are.

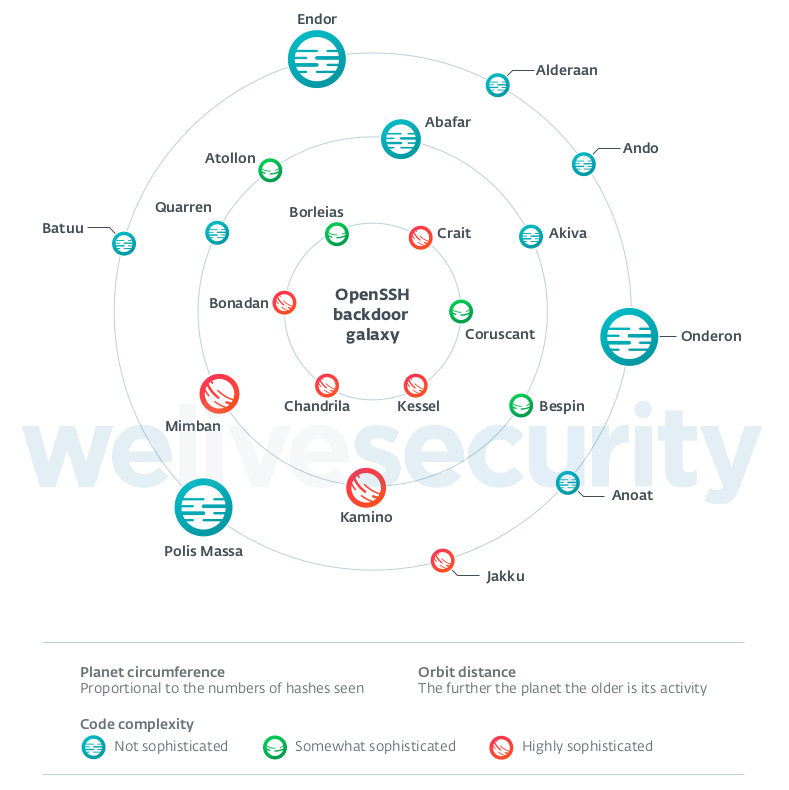

This graphic sums up the OpenSSH backdoor families from this research. Some of our readers will surely have recognized these names as corresponding to planets from the Star Wars saga. Note that they do not correspond to ESET’s detection names; it is just a convenient way to identify them in our research. Their detection names and various IoC data are provided in the white paper and on our GitHub IoC repository.

Evaluating complexity for a family could be subjective. We have tried to be as objective as possible and base our classification on several factors, including:

- The presence of an exfiltration technique – presence of C&C server, network protocol, encryption in transport or storage, etc.

- The implementation of modules providing features additional to OpenSSH – additional commands, cryptocurrency mining, etc.

- The use of encryption or obfuscation to make analysis more difficult.

Each family has its own complete description in the full report, but the galaxy representation still gives some takeaways:

- According to our sample set, code complexity is increasingly important for the most recent families.

- We collected more samples for the older and simpler (often off-the-shelf) families. This can be explained by the fact that more sophisticated ones are more difficult to detect and less prevalent.

Visiting some interesting planets

Some of the backdoors we found aren’t particularly new or interesting from a technical point-of-view. There are, however, quite a few exceptions showing that some attackers are putting a lot of effort into maintaining their botnets.

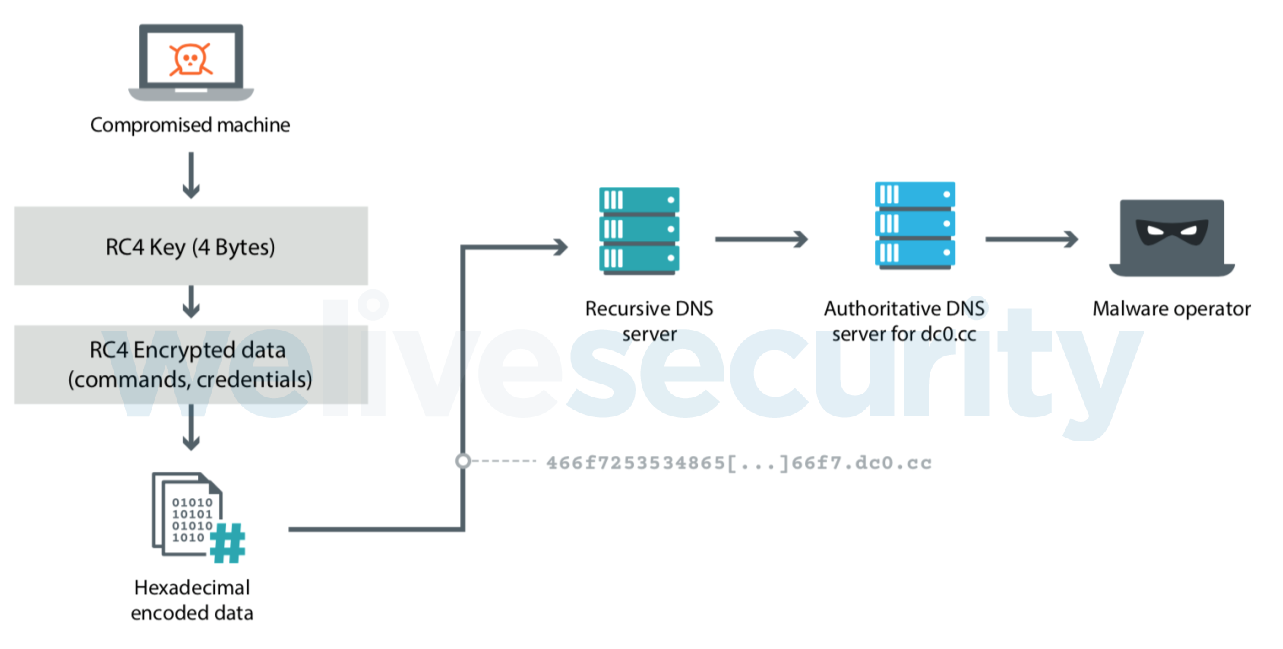

One of these is Kessel. Kessel stands out for its multiple methods of communicating with its C&C server. It implements HTTP, raw TCP and DNS. Besides asking for stolen credentials, the C&C server also has the ability to send additional commands such as downloading from or uploading files to the compromised machine. All communication with its C&C server is also encrypted. It is also quite new: the C&C server domain was registered in August 2018.

Kessel DNS exfiltration

Another such example is Kamino. From analysis of the samples, we discovered this threat has existed for a long time and evolved, both in its obfuscation techniques and usage. It was first used by a crimeware campaign known to leverage the DarkLeech malware to redirect traffic, as documented by ESET researchers in 2013. Interestingly, it is the same backdoor that was used on attacks against Russian banks by a group called Carbanak years later, as described by Group-IB. This shift from crimeware to more targeted attacks is intriguing. It is tempting to think both attacks are from the same group, but it could also be explained by the original authors selling their code to multiple crime groups.

Detailed analyses of Chandrila (passing data in passwords) and Bonadan (cryptocurrency mining features) are also provided in the white paper.

Mitigation and detection

Since the data we analyzed were mostly malware samples taken out of their context, it is difficult to identify their original infection vectors. Techniques could include: using credentials stolen after a victim used a compromised SSH client, brute force or exploitation of a vulnerable service exposed by the server.

Any of the mentioned attack vectors might be used in future attacks, thus all good practices aimed at preventing a system from being compromised should be followed:

- Keep the system up-to-date.

- Favor key-based authentication for SSH.

- Disable remote root login.

- Use a multi-factor authentication solution for SSH.

ESET products detect the analyzed OpenSSH backdoors as Linux/SSHDoor variants. Additionally, the YARA ruleset we used can help to classify the potential samples. The paper gives more details about validating OpenSSH files using Linux package managers to verify the integrity of installed executables.

Conclusion

With this research, we hope to shed light on OpenSSH backdoors and, by extension, on Linux malware in general. As observed through the diversity of code complexity, some attackers simply reuse available source code, while others put real effort into their bespoke implementations. Moreover, the active hunt via our custom honeypot structure shows that some attackers are still active and are very cautious when deploying their backdoors.

After reading the paper you may feel that there is more Linux malware now than before; that this is a rising trend. We don’t think this is necessarily the case: there has always been Linux malware but due to a lack of visibility it stays under the radar for a longer period.

There are still a lot of unanswered questions: how prevalent is each of these families? How are compromised systems used by the attackers? Besides stealing credentials, do they use additional techniques to propagate?

ESET researchers believe that system administrators and malware researchers can help each other in the fight against server-side malware. Feel free to reach us at threatintel@eset.com if you have additional details about the backdoors we have described (or have not described) or if you have any questions.