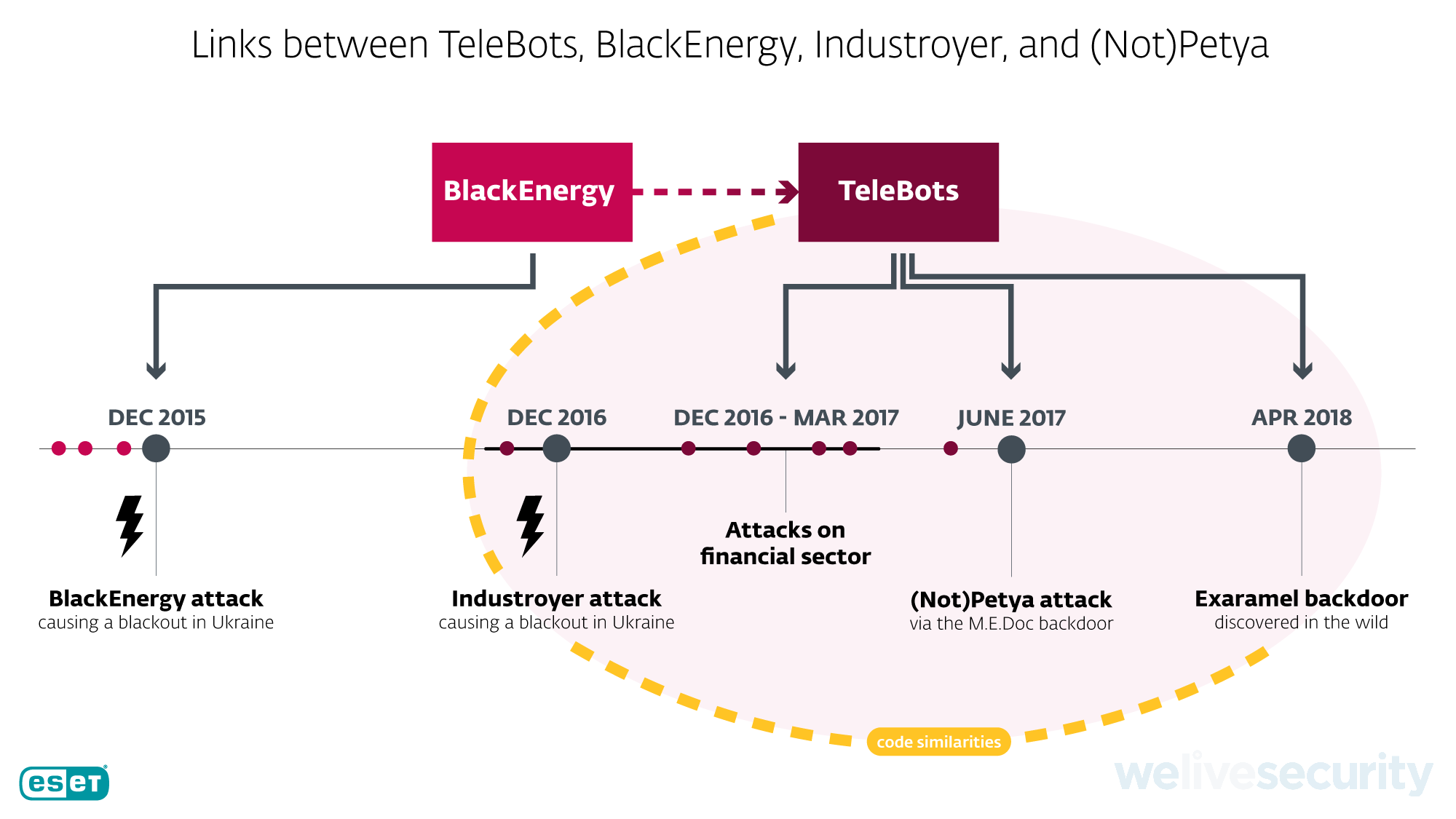

Among the most significant malware-induced cybersecurity incidents in recent years were the attacks against the Ukrainian power grid – which resulted in unprecedented blackouts two years in a row – and the devastating NotPetya ransomware outbreak. Let’s take a look at the links between these major incidents.

The first ever malware-enabled blackout in history, which happened in December 2015, was facilitated by the BlackEnergy malware toolkit. ESET researchers have been following the activity of the APT group utilizing BlackEnergy both before and after this milestone event. After the 2015 blackout, the group seemed to have ceased actively using BlackEnergy, and evolved into what we call TeleBots.

It is important to note that when we describe ‘APT groups’, we’re drawing connections based on technical indicators such as code similarities, shared C&C infrastructure, malware execution chains, and so on. We’re typically not directly involved in the investigation and identification of the individuals writing the malware and/or deploying it, and the interpersonal relations between them. Furthermore, the term ‘APT group’ is very loosely defined, and often used simply to cluster the abovementioned malware indicators. This is also one of the reasons why we refrain from speculations with regard to attributing attacks to nation states and such.

That said, we have observed and documented ties between the BlackEnergy attacks – not only those against the Ukrainian power grid but against various sectors and high-value targets – and a series of campaigns (mostly) against the Ukrainian financial sector by the TeleBots group. In June 2017, when many large corporations worldwide were hit by the Diskcoder.C ransomware (aka Petya and NotPetya) – most probably as unintended collateral damage – we discovered that the outbreak started spreading from companies afflicted with a TeleBots backdoor, resulting from the compromise of the financial software M.E.Doc, popular in Ukraine.

So how does Industroyer, the sophisticated malware framework used to cause the blackout of December 2016, fit into all of this? Right after we publicly reported our discovery, some security companies and news media outlets started to speculate that Industroyer was also architected by the BlackEnergy/Telebots group (sometimes also referred to as Sandworm). Yet, no concrete evidence has been publicly disclosed until now.

In April 2018, we discovered new activity from the TeleBots group: an attempt to deploy a new backdoor, which ESET detects as Win32/Exaramel. Our analysis suggests that this TeleBots’ backdoor is an improved version of the main Industroyer backdoor – the first piece of evidence that was missing.

Analysis of the Win32/Exaramel backdoor

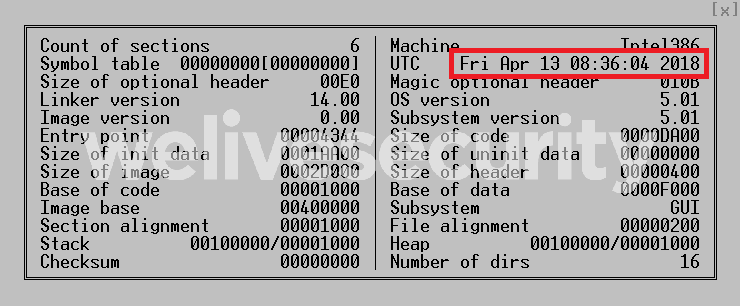

The Win32/Exaramel backdoor is initially deployed by a dropper. Metadata in this dropper suggest that the backdoor is compiled using Microsoft Visual Studio just before deployment on a particular, victimized computer.

Figure 1. PE timestamp in the dropper of Win32/Exaramel backdoor

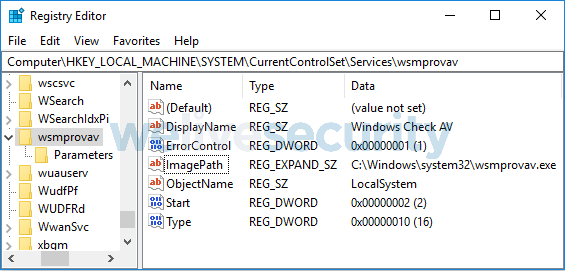

Once executed, the dropper deploys the Win32/Exaramel backdoor binary in the Windows system directory and creates and starts a Windows service named wsmprovav with the description "Windows Check AV". The filename and the Windows service description are hardcoded into the dropper.

Figure 2. Registry settings of the Windows service created by the Win32/Exaramel backdoor

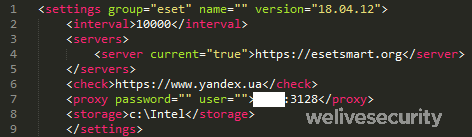

In addition, the dropper writes the backdoor's configuration into the Windows registry, in XML format.

Figure 3. Win32/Exaramel backdoor XML configuration

The configuration contains several blocks:

Interval – time in milliseconds used for Sleep function

Servers – list of command and control (C&C) servers

Check – website used to determine whether the host has an internet connection available

Proxy – proxy server on the host network

Storage – path used for storing files scheduled for exfiltration

As can be seen from the first line of the configuration, the attackers are grouping their targets based on the security solutions in use. Similar behavior can be found in the Industroyer toolset – specifically some of the Industroyer backdoors were also disguised as an AV-related service (deployed under the name avtask.exe) and used the same grouping.

Another interesting fact is that the backdoor uses C&C servers with domain names that mimic domains belonging to ESET. In addition to esetsmart[.]org from the above mentioned configuration, we found another similar domain: um10eset[.]net, which was used by recently-discovered Linux version of Telebots malware. It is important to note that these attacker-controlled servers are in no way related to ESET’s legitimate server infrastructure. Currently, we haven’t seen Exaramel use domains that mimic other security companies.

Once the backdoor is running, it connects to a C&C server and receives commands to be executed. Here is a list of all available commands:

- Launch process

- Launch process under specified Windows user

- Write data to a file in specified path

- Copy file into storage sub-directory (Upload file)

- Execute shell command

- Execute shell command as specified Windows user

- Execute VBS code using MSScriptControl.ScriptControl.1

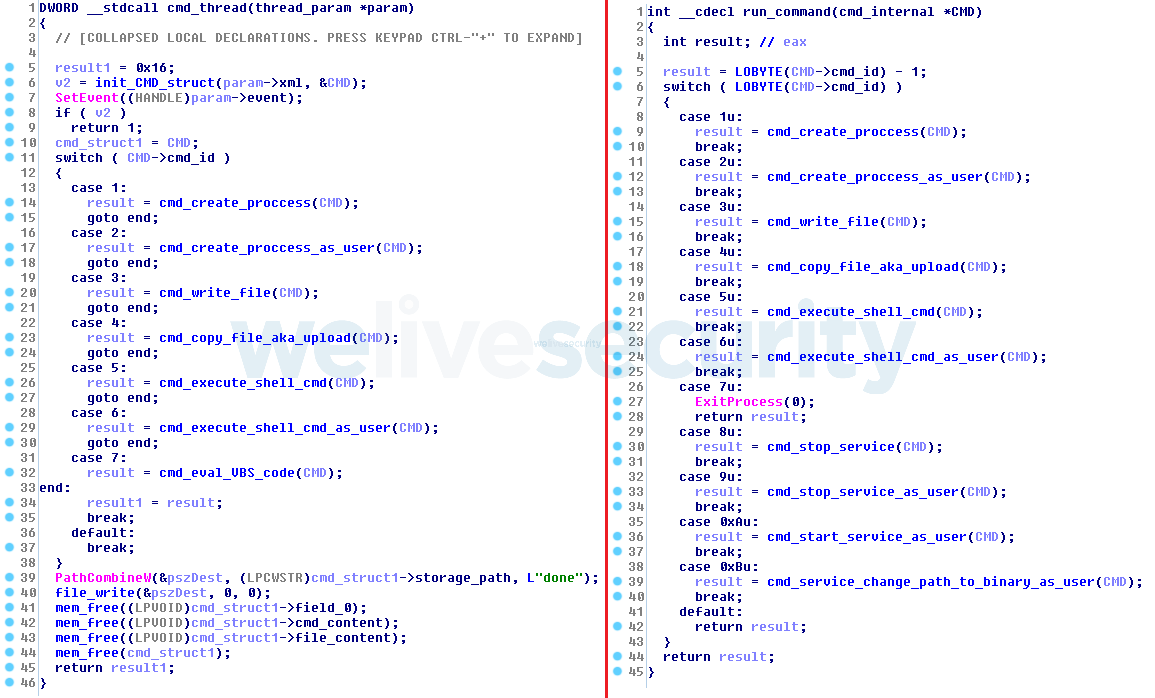

The code of the command loop and implementations of the first six commands are very similar to those found in a backdoor used in the Industroyer toolset.

Figure 4. Comparison between decompiled code of the Win32/Exaramel backdoor (on the left) and the Win32/Industroyer backdoor (on the right)

Both malware families use a report file for storing the resulting output of executed shell commands and launched processes. In case of the Win32/Industroyer backdoor, the report file is stored in a temporary folder under a random filename; in case of the Win32/Exaramel backdoor, the report file is named report.txt and its storage path is defined in the backdoor’s configuration file.

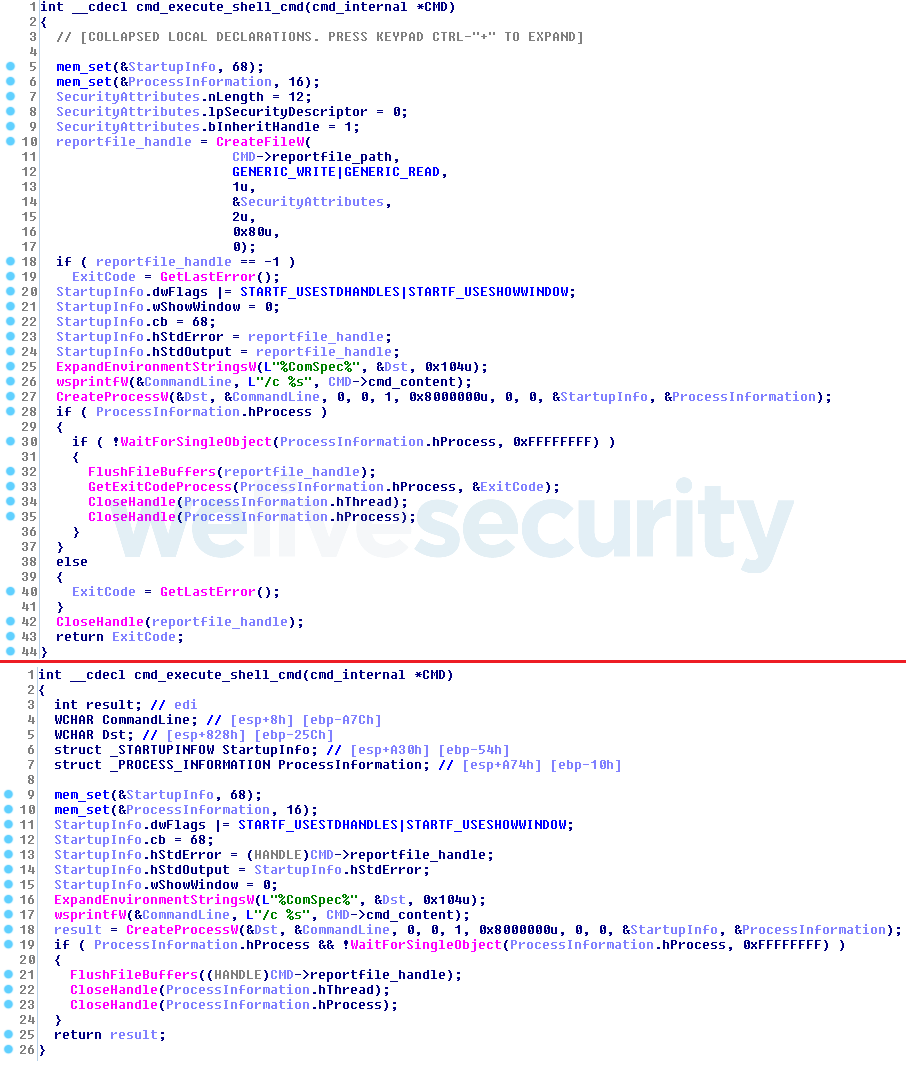

In order to redirect standard output (stdout) and standard error (stderr) to the report file, both backdoors set the hStdOutput and hStdError parameters to a handle of the report file. This is another design similarity between these malware families.

Figure 5. Comparison between decompiled code of the Win32/Exaramel backdoor (on the top) and the Win32/Industroyer backdoor (on the bottom)

If the malware operators want to exfiltrate files from the victim’s computer, they just need to copy those files into the data sub-directory of the storage path defined in the configuration. Once the backdoor is about to make a new connection to the C&C server it will automatically compress and encrypt all these files before sending them.

The main difference between the backdoor from the Industroyer toolset and this new TeleBots backdoor is that the latter uses XML format for communication and configuration instead of a custom binary format.

Password stealing malicious tools

Along with the Exaramel backdoor, Telebots group uses some of their old tools, including a password stealer (internally referred as CredRaptor or PAI by the attackers) and a slightly-modified Mimikatz.

The CredRaptor custom password-stealer tool, exclusively used by this group since 2016, has been slightly improved. Unlike previous versions, it collects saved passwords not only from browsers, but also from Outlook and many FTP clients. Here is a list of supported applications:

- BitKinex FTP

- BulletProof FTP Client

- Classic FTP

- CoffeeCup

- Core FTP

- Cryer WebSitePublisher

- CuteFTP

- FAR Manager

- FileZilla

- FlashFXP

- Frigate3

- FTP Commander

- FTP Explorer

- FTP Navigator

- Google Chrome

- Internet Explorer 7 – 11

- Mozilla Firefox

- Opera

- Outlook 2010, 2013, 2016

- SmartFTP

- SoftX FTP Client

- Total Commander

- TurboFTP

- Windows Vault

- WinSCP

- WS_FTP Client

This improvement allows attackers to collect webmaster’s credentials for websites and credentials for servers in internal infrastructure. Once access to such servers is obtained, attackers could plant additional backdoors there. Quite often these servers are operated by OSes other than Windows, so attackers have to adapt their backdoors.

In fact, during our incident response, we discovered a Linux backdoor used by TeleBots. We named this backdoor Linux/Exaramel.A.

Analysis of the Linux/Exaramel backdoor

The backdoor is written in the Go programming language and compiled as a 64-bit ELF binary. Attackers can deploy the backdoor in a chosen directory under any name.

If the backdoor is executed by attackers with the string ‘none’ as a command line argument, then it attempts to use persistence mechanisms in order to be started automatically after reboot. If the backdoor is not executed under the root account, then it uses the crontab file. However, if running as root, it supports different Linux init systems. It determines which init system is currently in use by executing the command:

strings /sbin/init | awk 'match($0, /(upstart|systemd|sysvinit)/){ print substr($0, RSTART, RLENGTH);exit; }'

Based on the result of this command, it uses the following hardcoded locations for its persistence:

| Init system | Location |

|---|---|

| sysvinit | /etc/init.d/syslogd |

| upstart | /etc/init/syslogd.conf |

| systemd | /etc/systemd/system/syslogd.service |

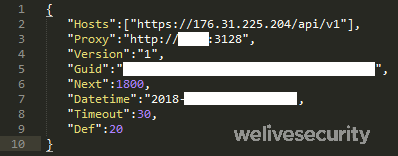

During startup, the backdoor attempts to open a configuration file named config.json, which is stored in the same directory as the backdoor. If this configuration file does not exist, then a new file is created. The configuration is encrypted using the key s0m3t3rr0r via the RC4 algorithm.

Figure 6. Decrypted JSON configuration of the Linux/Exaramel backdoor

The backdoor connects to the hardcoded C&C server (by default 176.31.225[.]204 in the sample we have seen to date) or to the C&C server listed in the configuration files Hosts value. The communication is sent over HTTPS. The backdoor supports the following commands:

| Command | Purpose |

|---|---|

| App.Update | Updates itself to a newer version |

| App.Delete | Deletes itself from the system |

| App.SetProxy | Sets proxy in configuration |

| App.SetServer | Updates C&C server in configuration |

| App.SetTimeout | Sets timeout value (time between connections to C&C server) |

| IO.WriteFile | Downloads a file from a remote server |

| IO.ReadFile | Uploads a file from local disk to C&C server |

| OS.ShellExecute | Executes a shell command |

Conclusion

The discovery of Exaramel shows that the TeleBots group is still active in 2018 and the attackers keep improving their tools and tactics.

The strong code similarity between the Win32/Exaramel backdoor and the Industroyer main backdoor is the first publicly-presented evidence linking Industroyer to TeleBots, and hence to NotPetya and BlackEnergy. While the possibility of false flags – or a coincidental code sharing by another threat actor – should always be kept in mind when attempting attribution, in this case we consider it unlikely.

Of particular interest is the fact that the attackers started to use ESET-themed domain names in their operations. It should be noted that these domains were used by cybercriminals in order to hide their malicious network activity from defenders and are in no way related to ESET’s server infrastructure. The list of legitimate domains used by ESET products can be found here.

It should also be noted that these Win32 and Linux Exaramel backdoors were detected at an organization that is not an industrial facility. ESET shared its findings ahead of time with Ukrainian investigation authorities and thanks to this cooperation the attack was successfully localized and prevented.

ESET researchers will continue to monitor the activity of this group.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

| ESET detection names |

|---|

| Win32/Exaramel trojan |

| Win32/Agent.TCD trojan |

| Linux/Agent.EJ trojan |

| Linux/Exaramel.A trojan |

| Win32/PSW.Agent.OEP trojan |

| Win32/RiskWare.Mimikatz.Z application |

| Win64/Riskware.Mimikatz.AI application |

| SHA-1 HASHES |

|---|

| TeleBots Win32/Exaramel backdoor |

| 65BC0FF4D4F2E20507874F59127A899C26294BC7 |

| 3120C94285D3F86A953685C189BADE7CB575091D |

| Password Stealer |

| F4C4123849FDA08D1268D45974C42DEB2AAE3377 |

| 970E8ACC97CE5A8140EE5F6304A1E7CB56FA3FB8 |

| DDDF96F25B12143C7292899F9D5F42BB1D27CB20 |

| 64319D93B69145398F9866DA6DF55C00ED2F593E |

| 1CF8277EE8BF255BB097D53B338FC18EF0CD0B42 |

| 488111E3EB62AF237C68479730B62DD3F52F8614 |

| Mimikatz |

| 458A6917300526CC73E510389770CFF6F51D53FC |

| CB8912227505EF8B8ECCF870656ED7B8CA1EB475 |

| Linux/Exaramel |

| F74EA45AD360C8EF8DB13F8E975A5E0D42E58732 |

Warning! All of the servers with these IP addresses were part of the Tor network, which means that the use of these indicators could result in a false positive match.

| C&C servers |

|---|

| um10eset[.]net (IP: 176.31.225.204) |

| esetsmart[.]org (IP: 5.133.8.46) |