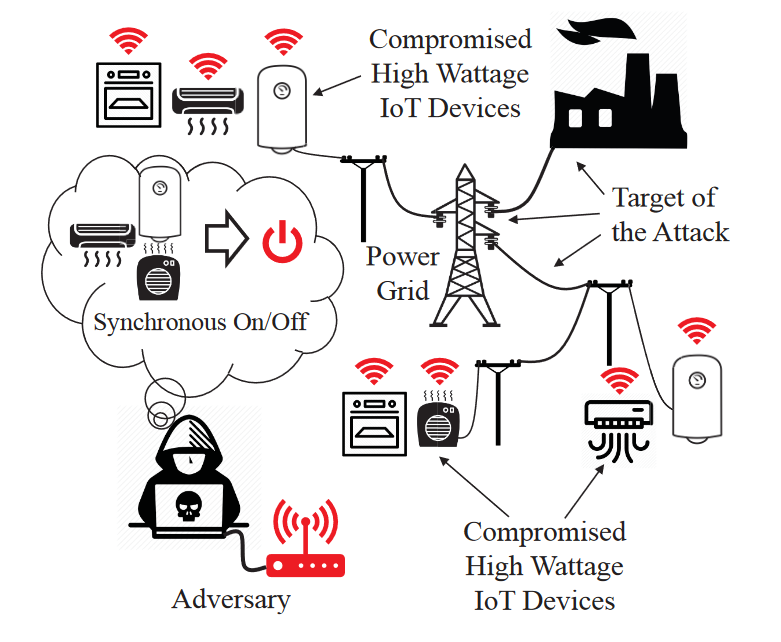

Cybercriminals could rope internet-connected household appliances into a botnet in order to manipulate the demand side of the power grid and, ultimately, cause anything from local outages to large-scale blackouts, according to a study from a team of academics at Princeton University.

Their research focused specifically on power-hungry domestic appliances like electric ovens, space heaters and air conditioners that can be connected to the internet and are often controlled via mobile applications or smart home hubs. They didn’t highlight any specific security flaws in any particular devices, but envisaged a scenario involving their compromise in some way by hackers.

The underlying – and unusual – threads of the proof-of-concept attacks are that threat actors could cause the disruption without compromising the grid’s supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems. Also, rather than taking aim directly at the network’s supply side, the attacks – nicknamed “MadIoT” (Manipulation of demand via IoT) – would target the demand side.

The sources of MadIoT attacks are “hard to detect and disconnect by the grid operator due to their distributed nature”, wrote the researchers. Moreover, the attacks can be easily repeated while requiring no knowledge of the grid’s operational details on the adversary’s part.

The researchers tested the plausibility of the new type of attack on “state-of-the-art simulators on real-world power grid models”. The threat is described in a paper called “BlackIoT: IoT Botnet of High Wattage Devices Can Disrupt the Power Grid”, and the research was also presented at a recent USENIX security symposium.

Before we dive into the ins and outs of MadIoT, a bit of an aside: actual attacks aimed at electricity supply interruption aren’t unheard of. Ukraine, for one, has experienced two attack-induced blackouts in recent years. ESET researchers have analyzed samples of malware known as Industroyer that was probably to blame for an hour-long outage that hit parts of Kiev and nearby areas in December 2016. That piece of malicious code was found to be capable of controlling electricity substation switches and circuit breakers directly, including in some cases literally switching them off and on.

Lights out

Back to MadIoT now. In a nutshell, the academics came up with three broad attack scenarios:

First, it’s attacks that result in frequency instability due to abrupt increases or decreases in the power demands of high-wattage internet-connected devices by simultaneously turning many of them on or off. The ensuing imbalance between supply and demand triggers a sudden drop in the system’s frequency.

“If the imbalance is greater than the system’s threshold, the frequency may reach a critical value that causes generators tripping and potentially a large-scale blackout,” wrote the academics.

A simulation on a power grid model of a US-based utility showed that a 30% increase in demand was enough to cause the tripping of all the generators. “For such an attack, an adversary requires access to about 90 thousand air conditioners or 18 thousand electric water heaters within the targeted geographical area,” reads the paper.

Second, threat actors could cause line failures by redistributing demand for power, the ultimate result being cascading grid failures. This would be done by increasing the demand in some places, for instance by switching on the appliances within one IP range, and by reducing the demand in other areas by turning appliances off within another IP range.

The authors used simulations to show that an increase of only 1% in demand in one particular sector of the Polish grid results in a cascading failure with 263 line failures and outage in 86% of the loads. "Such an attack by the adversary requires access to about 210 thousand air conditioners which is 1.5% of the total number of households in Poland,” reads the paper.

In the third scenario, the demand curve could be manipulated with an eye towards increasing the operating cost of the grid to the benefit of selected utilities on the electricity market. For instance, by forcing the demand for power to go above the predicted value, adversaries could force the grid’s operator to purchase additional power and at higher cost from a reserve generator – obviously to harm the former while benefitting the latter. In this case, the attack would be driven by financial motives, rather than with the aim of damaging the infrastructure.

Arguably, MadIoT attacks bear some resemblance to distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, where devices conscripted into a botnet inundate a target such as a website or server with so much traffic that the service becomes unavailable. A series of DDoS attacks that were carried out by a botnet of 600,000 hacked IoT devices on August 21, 2016 and caused widespread disruption of legitimate internet activity in the US is a fitting example.

One limitation of MadIoT attacks is that, unlike in DDoS attacks, the compromised bots would need to be located within the boundaries of a power system in a particular area, rather than scattered across the world.

A future threat?

“[O]ur work sheds light upon the interdependency between the vulnerability of the IoT and that of other networks such as the power grid whose security requires attention from both the systems security and the power engineering communities,” according to the academics, who went on to sketch out a set of recommendations to the relevant stakeholders.

Most importantly, grid operators should make sure that their infrastructure is ready to withstand abrupt load changes. At the same time, IoT device manufacturers should conduct rigorous testing of their appliances for vulnerabilities, thus making sure that the devices aren’t sitting ducks for cyberattacks.

A few weeks ago, a different team of researchers identified and analyzed security flaws in the firmware of several commercial internet-connected irrigation systems that could enable attackers to remotely turn watering systems on and off at will. The researchers warned of a potential attack that – using a “botnet” of internet-connected irrigation systems that water simultaneously – could impact a city’s water system to the point of actually draining its reserves.