Researchers claim to have devised a way of browsing the web that “patches security holes left open by web browsers’ private-browsing functions”, reads the press announcement by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

The newly-proposed method, aptly called ‘Veil’, may thus be of interest for web users who wish not to leave any trace of their browsing activity on local devices, be they their own, shared or public.

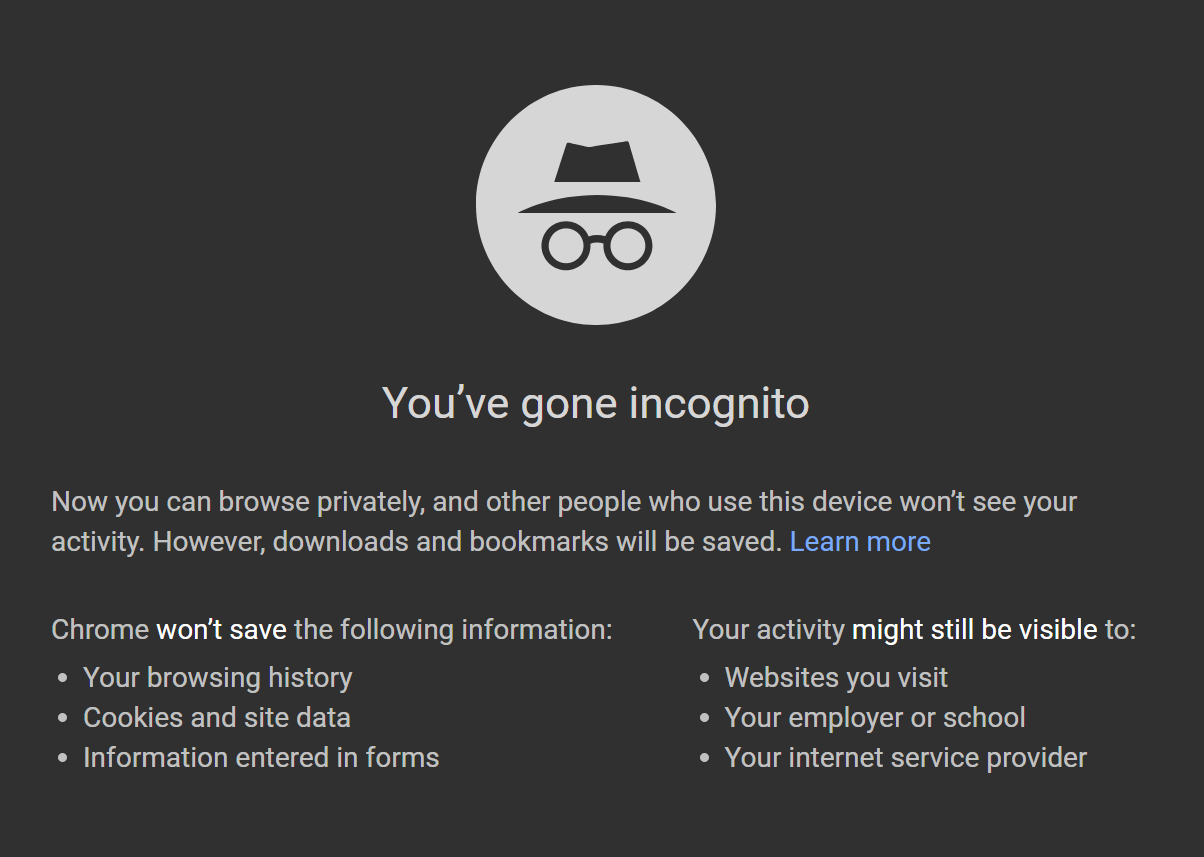

Internet browsers – when run in privacy (also known as incognito) mode – are designed not to record the browsing history on the device. They may not necessarily be foolproof, however, and may still leave some traces behind, according to three academics at MIT and Harvard University. They describe their new framework in a paper called Veil: Private Browsing Semantics Without Browser-side Assistance.

Incognito?

With private-mode browsing sessions in their existing implementations, a browser loads data into memory and, once the session is terminated, it attempts to erase all such traces, explained the researchers.

The success of such clean-ups may vary, however. “Data accessed during private browsing sessions can still end up tucked away in a computer’s memory, where a sufficiently motivated attacker could retrieve it,” reads the press release.

In addition, due to the complexities of memory management, the data may even wind up on (and later be retrieved from) the hard drive. This would happen with zero awareness on the part of the browser, which is then unable or even unauthorized to wipe it.

“Generally, a browser won’t know where the data it downloaded has ended up,” according to the academics.

“Veil was motivated by all this research that was done previously in the security community that said, ‘Private-browsing modes are leaky — Here are 10 different ways that they leak,” Frank Wang, one of the paper’s authors, is quoted as saying.

“We asked, ‘What is the fundamental problem?’ And the fundamental problem is that [the browser] collects this information, and then the browser does its best effort to fix it. But at the end of the day, no matter what the browser’s best effort is, it still collects it. We might as well not collect that information in the first place,” he added.

The disclaimer in Google Chrome’s Incognito mode.

The cloak

So what is Veil’s not-so-secret sauce for private browsing? In a nutshell, it’s encryption and a dedicated server, peppered with some garbage code.

First, the user types a URL into the Veil website, rather than into the browser’s address bar. A server, which the researchers dubbed a “blinding server”, fetches an encrypted webpage. The webpage comes embedded with code that executes a decryption algorithm, but the page itself remains encrypted until the moment it’s shown on the screen.

Once unscrambled, the data remains in memory only for as long as the webpage appears on the screen. “That type of temporarily stored data is less likely to be traceable after the browser session is over,” according to Veil’s creators.

Should that not be enough to frustrate particularly dedicated attackers, the team claims to have some more tricks up its sleeve.

"Once unscrambled, the data remains in memory only for as long as the webpage appears on the screen"

The blinding server randomly adds some nonsense code to every webpage. This ‘code obfuscation’, according to the academics, has no effect on what the actual page looks like, but it drastically changes the appearance of the underlying source file. That way, even if attackers got their hands on a few snippets of the decrypted code, ultimately they would be likely to come out empty-handed and unable to piece together the browsing history.

Optionally, Veil can step up its privacy game further. The blinding server is able to send only an image of the requested page, rather than the page itself. If a user clicks on some part of the picture, the server will fetch a picture of the updated page. At no point does the user receive any executable code.

The pages displayed via Veil retain their usual appearance, said the researchers. Their new system can reportedly be used in conjunction with current private-browsing implementations and even with the anonymizer network Tor.

To make Veil work, however, web developers would need to create Veil-compatible versions of their websites. In order to automate this process, the researchers have devised a compiler so that the developers can simply feed their existing website content into it.

“A slightly more demanding requirement is the maintenance of the blinding servers,” according to the researchers. They voiced their hope that volunteers, or even web services that pride themselves on providing extra safeguards for their privacy-minded customers, could host the servers.