ESET researchers have found that Turla, the notorious state-sponsored cyberespionage group, has added a fresh weapon to its arsenal that is being used in new campaigns targeting embassies and consulates in the post-Soviet states. This new tool attempts to dupe victims into installing malware that is ultimately aimed at siphoning off sensitive information from Turla’s targets.

The group has long used social engineering to lure unsuspecting targets into executing faux Adobe Flash Player installers. However, it doesn’t rest on its laurels and continues to innovate, as shown by recent ESET research.

Not only does the gang now bundle its backdoors together with a legitimate Flash Player installer but, compounding things further, it ensures that URLs and the IP addresses it uses appear to correspond to Adobe’s legitimate infrastructure. In so doing, the attackers essentially misuse the Adobe brand to trick users into downloading malware. The victims are made to believe that the only thing that they are downloading is authentic software from adobe.com. Unfortunately, nothing could be further from the truth.

The campaigns, which have been leveraging the new tool since at least July 2016, bear several hallmarks associated with the group, including Mosquito, a backdoor believed to be the group’s creation, and the use of IP addresses previously linked with the group. The new malicious tool also shares similarities with other malware families spread by the group.

Attack vectors

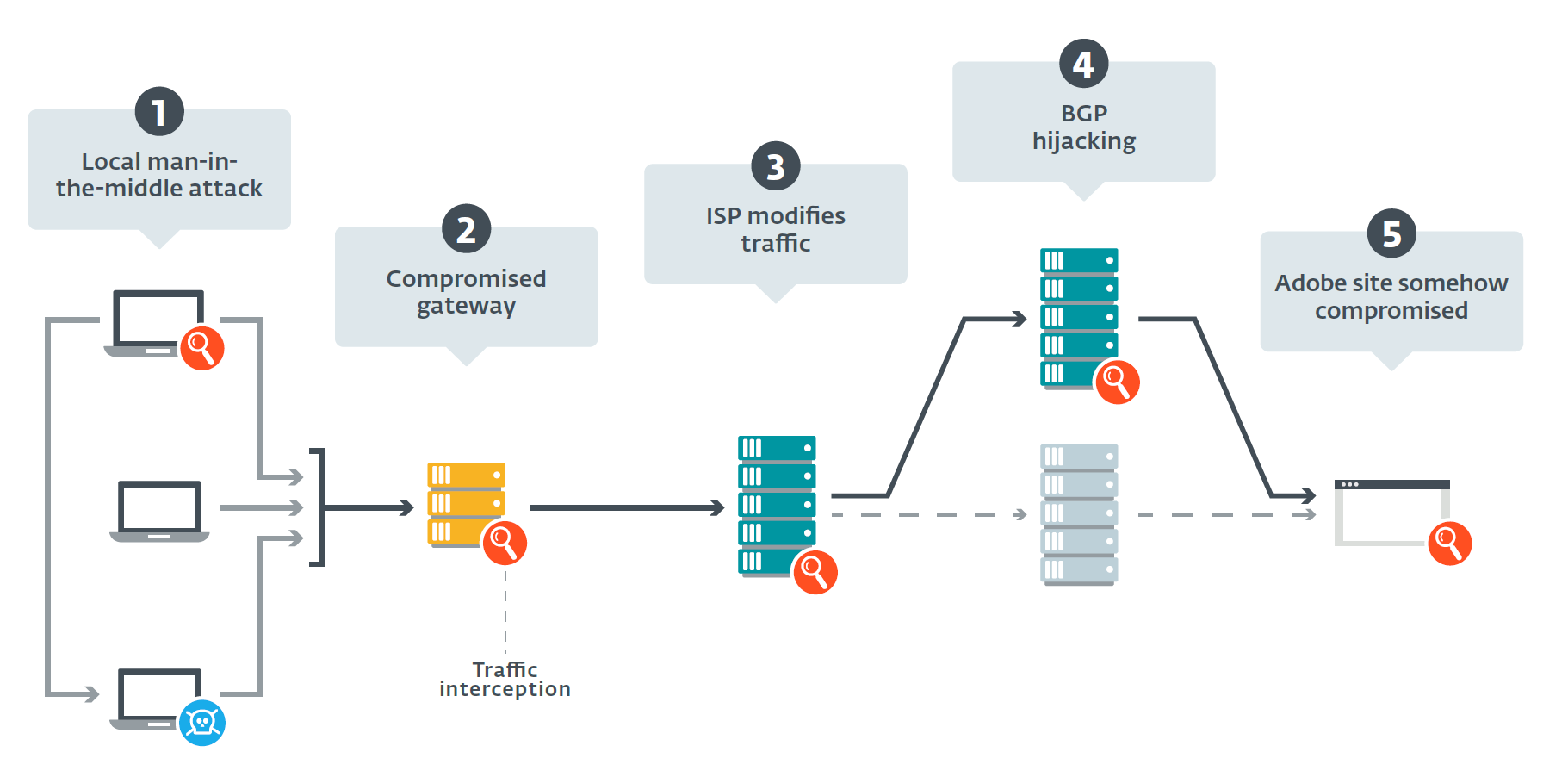

ESET researchers have come up with several hypotheses (shown in Figure 1) for how Turla-related malware can make it onto a victim’s computer via the new method of compromise. Importantly, however, it is safe to rule out a scenario involving some sort of compromise of Adobe. Turla’s malware is not known to have tainted any legitimate Flash Player updates, nor is it associated with any known Adobe product vulnerabilities. The possibility involving a compromise of the Adobe Flash Player download website has also been practically discarded.

Figure 1: Possible interception points on the path between the potential victim’s machine and the Adobe servers. Note that the scenario under #5 is seen as very unlikely.

The possible attack vectors ESET researchers considered are:

- A machine within the network of the victim’s organization could be hijacked so that it acts as a springboard for a local Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attack. This would effectively involve on-the-fly redirection of the traffic of the targeted machine to a compromised machine on the local network.

- The attackers could also compromise the network gateway of an organization, enabling them to intercept all the incoming and outgoing traffic between that organization’s intranet and the internet.

- The traffic interception could also occur at the level of internet service providers (ISPs), a tactic that – as evidenced by recent ESET research into surveillance campaigns deploying FinFisher spyware – is not unheard of. All the known victims are located in different countries, and we identified them using at least four different ISPs.

- The attackers could have used a Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) hijack to re-route the traffic to a server controlled by Turla, although this tactic would probably rather quickly set off alarm bells with Adobe or BGP monitoring services.

Once the fake Flash installer is downloaded and launched, one of several backdoors is dropped. It could be Mosquito, which is a piece of Win32 malware, a malicious JavaScript file communicating with a web app hosted on Google Apps Script, or an unknown file downloaded from a bogus and non-existent Adobe URL.

The stage is then set for the mission’s main goal – exfiltration of sensitive data. This information includes the unique ID of the compromised machine, the username, and the list of security products installed on the device. ‘Only’ the username and device name are exfiltrated by Turla’s backdoor Snake on macOS.

At the final part of the process, the fake installer drops – or downloads – and then runs a legitimate Flash Player application. The latter’s installer is either embedded in its fake counterpart or is downloaded from a Google Drive web address.

Mosquito and JavaScript backdoors

ESET researchers have seen in the wild, new samples of the backdoor known as Mosquito. The more recent iterations are more heavily obfuscated with what appears to be a custom crypter, to make analysis more difficult both for malware researchers and for security software’s code.

In order to establish persistence on the system, the installer tampers with the operating system’s registry. It also creates an administrative account that allows remote access.

The main backdoor CommanderDLL has the .pdb extension. It uses a custom encryption algorithm and can execute certain predefined actions. The backdoor keeps track of everything it does on the compromised machine in an encrypted log file.

Turla has been operating for a number of years and its activities have been monitored and analyzed by ESET research laboratories. Last year, the analysts released pieces covering new versions of another Turla backdoor called Carbon, watering hole campaigns misusing a Firefox browser extension and, most recently, a backdoor called Gazer.

Read ESET’s latest findings about Turla here in: Diplomats in Eastern Europe bitten by a Turla mosquito