The digital technologies that enable much of what we think of as modern life have introduced new risks into the world and amplified some old ones. Attitudes towards risks arising from our use of both digital and non-digital technologies vary considerably, creating challenges for people who seek to manage risk. This article tells the story of research that explores such challenges, particularly with respect to digital technology risks such as the theft of valuable data, unauthorized exposure of sensitive personal information, and unwanted monitoring of private communications; in other words, threats that cybersecurity professionals have been working hard to mitigate.

The story turned out to be longer than expected so it is delivered in two parts, but here is the TL;DR version of the whole story:

- The security of digital systems (cybersecurity) is undermined by vulnerabilities in products and systems.

- Failure to heed experts is a major source of vulnerability.

- Failure to heed experts is a known problem in technology.

- The cultural theory of risk perception helps explain this problem.

- Cultural theory exposes the tendency of some males to underestimate risk (White Male Effect or WME).

- Researchers have assessed the public's perceptions of a range of technology risks (digital and non-digital).

- Their findings provide the first ever assessment of WME in the digital or cyber-realm.

- Additional findings indicate that cyber-related risks are now firmly embedded in public consciousness.

- Practical benefits from the research include pointers to improved risk communication strategies and a novel take on the need for greater diversity in technology leadership roles.

Of course, I am hopeful a lot of people will find time to read all of both parts of the article, but if you only have time to read a few sections then the headings should guide you to items of interest. I am also hopeful that my use of the word cyber will not put you off – I know some people don’t like it, but I find it to be a useful stand-in for digital technologies and information systems; for example, the term cyber risk is now used by organizations such as the Institute of Risk Management to mean “any risk of financial loss, disruption, or damage to the reputation of an organization from some sort of failure of its information technology systems”. (I think it is reasonable to use cyber risk in reference to individuals as well, for example, the possibility that my online banking credentials are hijacked is a cyber risk to me.)

The sources of cyber risk

Like most research projects, this one began with questions. Why do some organizations seem to “get” security while others apparently do not? Why is it that, several decades into the digital revolution, some companies still ship digital products with serious “holes” in them, vulnerabilities that leak sensitive data or act as a conduit to unauthorized system access. Why do some people engage in risky behavior – like opening “phishy” email attachments – while others do not?

These questions can be particularly vexing for people who have been working in cybersecurity for a long time, people like myself and fellow ESET security researcher, Lysa Myers, who worked on this project with me. Again and again we have seen security breaches occur because people did not heed advice that we and other people with expertise in security have been disseminating for years, advice about secure system design, secure system operation, and appropriate security strategy.

When Lysa and I presented our research in this area to the 2017 (ISC)2 Security Congress we used three sources of vulnerability in information systems as examples:

- People and companies that sell products that have vulnerabilities in them (e.g. 1.4 million Jeeps and other FCA vehicles found to be seriously hackable and hard to patch, or hundreds of thousands of webcams and DVRs with hardcoded passwords used in the Mirai DDoS attack on DNS provider Dyn)

- People that don’t practice proper cyberhygiene (e.g. using weak passwords, overriding security warnings, clicking on dodgy email attachments)

- Organizations that don’t do security properly (e.g. obvious errors at Target, Equifax, JPMorgan Chase, Trump Hotel Collection)

Could it simply be that some percentage of people don’t accept that digital technology is as risky as experts say? Fortunately, the phenomenon of “failure to heed experts” has already been researched quite extensively, often in the context of technology risks. Some of that research was used in the project described here. (A good place to start reading about this research is CulturalCognition.net).

Technology risks in general

Risk is a surprisingly modern concept. For example, risk it is not a word that Shakespeare would have used (it does not appear in any of his writings). The notion of risk seems to have gained prominence only with the widespread use of technology. For example, advances in maritime technology enabled transoceanic commerce, which created risks for merchants shipping goods, which led to the development of financial instruments based on risk calculations, namely insurance policies (for more on the history of risk and risk management see: The New Religion of Risk Management by Peter L. Bernstein, author of Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk).

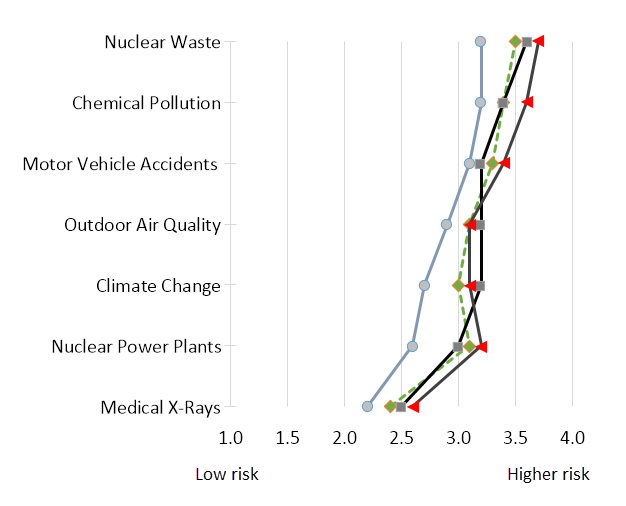

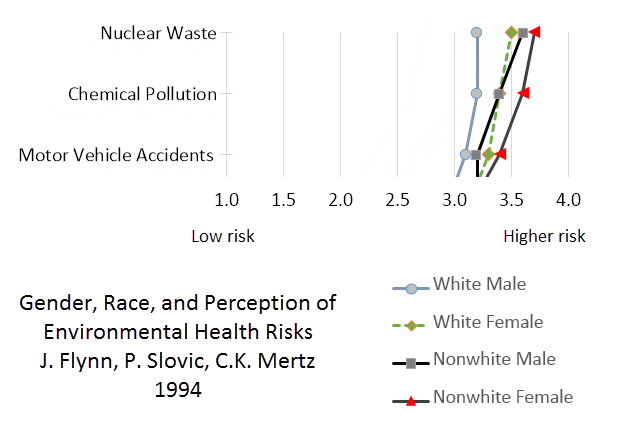

Over time, risks arising from complex and widespread technologies and behaviors became matters of public concern and debate. For example, the widespread use of fossil fuels created risks to human health from air pollution. The development of “cleaner” nuclear energy caused heated debate about the hazards of nuclear waste disposal. In Figure 1 below you can see how 1,500 American adults rated the risks from seven technology-related hazards in a landmark 1994 survey, broken down into four demographic groups:

The scale goes from lower risk on the left to higher risk on the right and you can see some hazards are perceived as riskier than others, for example, nuclear waste was perceived to be a higher risk than climate change. However, for some risks there were clearly differences in risk perception between the four groups (chart adapted from Flynn, Slovic and Mertz, 1994).

Before revealing the identity of those four groups, the relevance to risk research of the variations in their risk scores needs some context. Attempts to reduce technology risks sometimes lead to strong disagreements, as the current debates about climate change attest. These disagreements can exist, and may well persist, even when there is broad scientific consensus regarding the underlying facts. For example, 97% of actively publishing climate scientists currently agree that climate-warming trends over the past century are extremely likely to be due to human activities; but fewer than half of US adults agree with those experts (Pew Research Center).

As you might expect, studies have found that “failure to heed experts” factor is not demographically consistent and can vary by gender, age, ethnicity, and other factors. It seems reasonable to suppose that knowledge of such variations could help security professionals improve the effectiveness with which they communicate risks.

Numerous studies have found that males tend to perceive less risk in technology than females, and people who identify as white see less risk than those who identify as non-white. That 1994 study actually found that white males saw less risk than white females, non-white males, and non-white females. That is the origin of the chart shown earlier, where the line of “lower risk” scores on the left represents white males. Here in Figure 2 is a closer look at how the top three risks are rated:

This phenomenon, clearly observable in the results from that survey, has been dubbed the White Male Effect or WME and it has appeared in the results of multiple risk-related studies. The existence of WME with respect to cyber risks will be addressed later in the article, but I do want to make one thing clear about WME: researchers have observed this effect “in the aggregate,” in other words, not all white males under-estimate risks relative to the mean. Some white males see a lot of risk where others see very little. There is strong indirect evidence of this in the information security profession, members of which clearly “get” the importance of cyber risks, yet are predominantly male (89% according the most recent (ISC)2 Work Force Study), and mainly white (according to my personal observations at every security conference I have ever attended).

This phenomenon, clearly observable in the results from that survey, has been dubbed the White Male Effect or WME and it has appeared in the results of multiple risk-related studies. The existence of WME with respect to cyber risks will be addressed later in the article, but I do want to make one thing clear about WME: researchers have observed this effect “in the aggregate,” in other words, not all white males under-estimate risks relative to the mean. Some white males see a lot of risk where others see very little. There is strong indirect evidence of this in the information security profession, members of which clearly “get” the importance of cyber risks, yet are predominantly male (89% according the most recent (ISC)2 Work Force Study), and mainly white (according to my personal observations at every security conference I have ever attended).

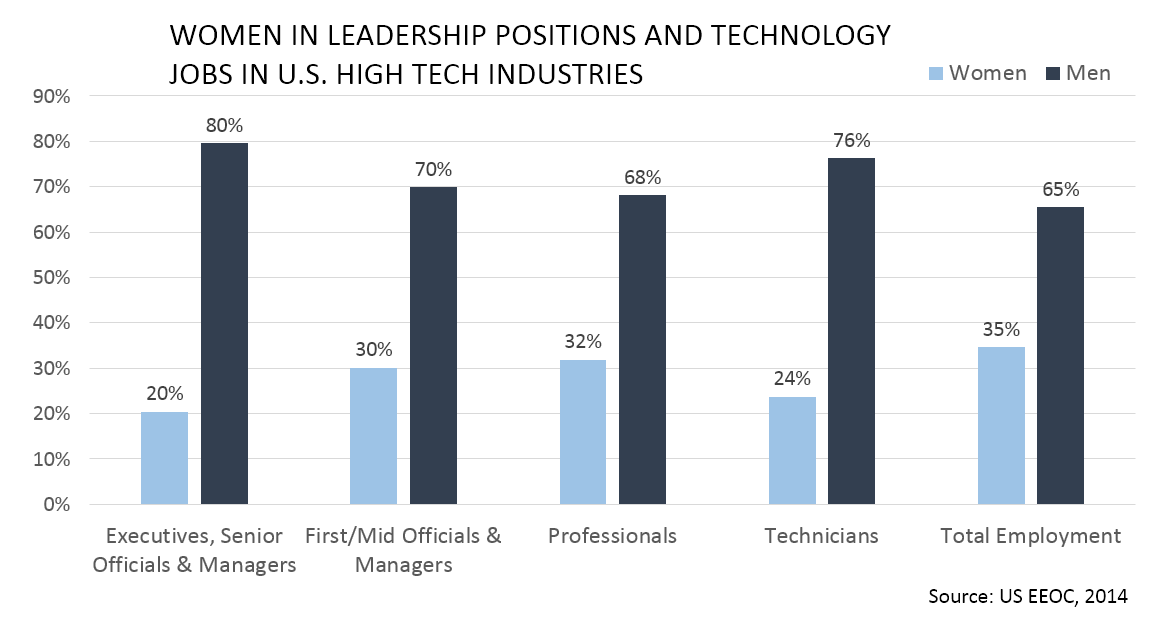

The diversity of risk perspectives within demographic groups is a matter of ongoing research, partly because something like WME has the potential to skew perspectives within organizations that are predominantly owned and run by white males, a point that I made in 2014 at TEDx, San Diego, in 2014. One could hypothesize that companies run by white males who under-estimate risk are more likely to sell risky products. While that is a hypothesis, the white male domination of upper management in high tech industries is a well-documented fact, as can be seen from Figure 3:

Cultural theory of risk

Over the years, several theories have been put forward to explain why the perception of risk varies from one person to another, and these studies are not merely an academic exercise. A clearer understanding of why risk perceptions vary has great potential to improve efforts to communicate risk and, by implication, overcome some of the “failure to heed experts” that arguably exacerbates the cybersecurity problem.

Intense debate about technological threats to the environment is not new, and in the 1970s an explanation for conflicting views of risk was put forward by Mary Douglas, a British anthropologist. She theorized that a society’s response to dangers will be shaped by the cultural values within that society. Working with Aaron Wildavsky, an American political scientist, Douglas presented the cultural theory of risk in the 1982 book Risk and Culture: An Essay on the Selection of Technical and Environmental Dangers. According to the cultural theory of risk, people may downplay risks that threaten their view of the social order and their place within that order. An extension of cultural theory is the notion of identity-protective cognition (see Kahan, 2008).

Cultural theory states that risks are defined, perceived, and managed “according to principles that inhere in particular forms of social organization” (Tansey and Rayner). In other words, “structures of social organization endow individuals with perceptions that reinforce those structures in competition against alternative ones” (Burgess).

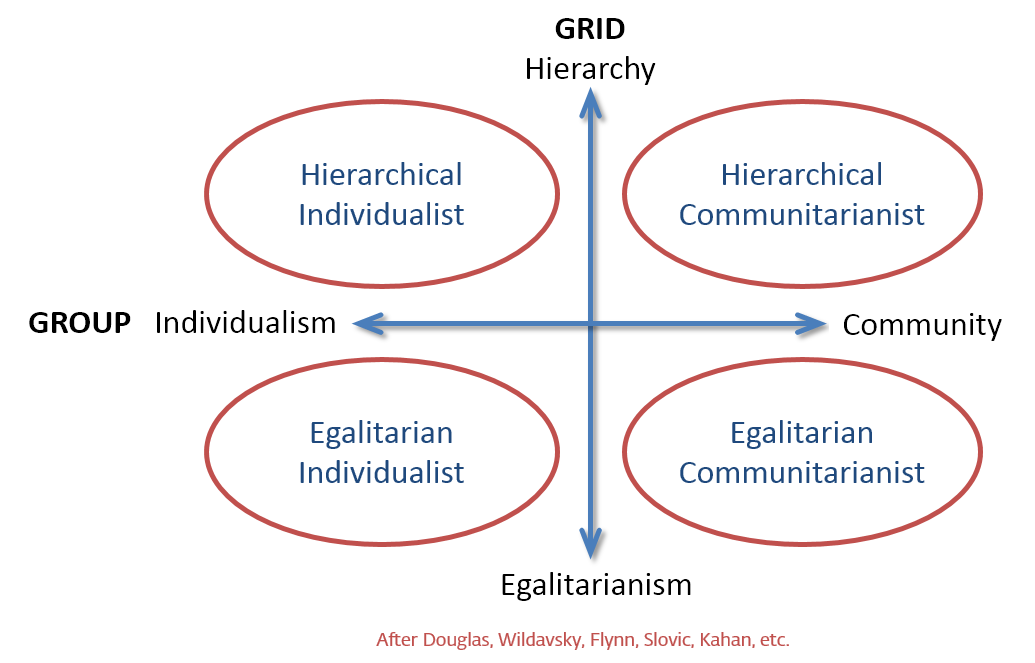

Although multiple cultural values exist in a large and complex society such as the US, Douglas suggested that they could all be categorized using just two dimensions: group and grid. The group dimension maps individuality versus community while the grid dimension maps hierarchy versus equality. There is not enough room here to go into great detail about the group-grid terminology, but the diagram in Figure 4 will help visualize what Douglas and Wildavsky had in mind:

What researchers have found, with remarkable consistency, is that group-grid alignment can predict risk perception. For example, people who see society as a hierarchy of individuals rather than as a community of equals typically rate global warming less risky than folks who are more egalitarian and communitarian. Claims that humans are the leading cause of climate change will be received differently by these groups, with hierarchists likely to reject them because they imply social elites are to blame, a prime example of identity-protective cognition.

Where does the white male effect fit into this? Further research found that a subset of white males drastically underrate risk relative to the mean and these men are predominantly hierarchical individualists. What researchers did not find is that these “low risk” males were lacking in education. Indeed, they tended to have above average education and income.

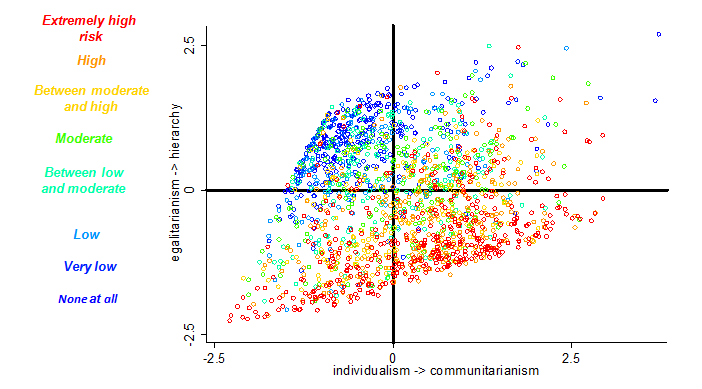

In order to better understand this phenomenon of culturally-motivated cognition, researchers developed a panel of questions, answers to which can be used to place survey respondents within the group-grid paradigm. Participants are asked to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with a series of statements such as “the government interferes far too much in our everyday lives” and “our society would be better off if the distribution of wealth was more equal”. The results enable mapping of risk perception according to the respondents’ group-grid placement. For example, in Figure 5 you can see a map of responses to a 2007 survey measuring global warming risk perception, where the “very low” and “no” risk respondents are mainly in the hierarchical-individualist quadrant (upper-left):

With all of the above as context, the story now turns to the risk perception survey that we carried out during the summer of 2017. As far as we know, this was the first study to look at both digital and non-digital hazards from a cultural theory perspective, and it produced some surprising results. You can read all about it in part 2.