I was a young mathematics professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) when I read Richard Dawkins’ description of memes. I recall thinking: “Oh, that’s how it all works”.

Memes are a generalization of genes, and, among other things, they include your beliefs. After studying memes for many decades, I have come to think that they are as indispensable to our understanding of human phenomena as genes are to our understanding of biological ones.

We still don’t have a solid scientific theory of memes; nonetheless, they already allow us to understand why certain things happen the way they do. Memes are “alive”; they reproduce, mutate, and evolve according to Darwinian laws. They struggle to survive. It is their struggle that creates and destroys religions, governments, and other institutions. It is their struggle that determines your behavior, your feelings, and how long you will live.

In my book “Memes” (an extend excerpt is available at leonardadleman.com), I single out three types of memes for special consideration: the ones stored as a sequence in a nucleic acid molecule (e.g. DNA or RNA) called genes; those stored in brains called brenes (portmanteau from brain and gene), and those stored in computers called Turenes (in honor of Alan Turing, the father of computer science).

Roughly speaking, the thing that makes genes, brenes, and Turenes special is that they alone have mastered the art of reproducing themselves. As a result, their struggles to avoid extinction can be particularly subtle and interesting.

In this article, I will focus on Turenes and the implications of meme-theory to topics of special interest to this blog: computer viruses, malware, and the future of computation. The reader may find it helpful to think of them as computer data – though they are far more than that.

The rise of the Turenes

Image: The first computer, ENIAC

On February 15, 1946, the first computer, ENIAC, was unveiled at the University of Pennsylvania. ENIAC used vacuum to store numbers – one of these numbers was the first Turene.

Humans added and multiplied Turenes, and occasionally copied them from one location to another, but Turenes had little control of their destinies; their fate was in the hands of humans (that is, in the hands of genes and brenes).

Just as self-replicating molecules emerged from the primordial soup several billion years ago, about a third of a century ago, Turenes began to self-replicate and exert significant control over their destinies. How? Well, this is a story WeLiveSecurity already shed some light on, but I’ll briefly address it again.

It was 1983. I was teaching a class on computer security at USC when a student, Fred Cohen, approached me with words to the effect: “I have an idea for a new kind of security threat”.

Fred proceeded to describe a program that would be made available to users of a computer system. Like an app today, the program would be advertised to do some useful task. But once uploaded (and hence copied) by an unsuspecting user (and at that time, no one suspected anything), the program would do something that had not been advertised; it would grant Fred access to all the user’s files and privileges.

Fred was, and is, a forceful, energetic person, and he finally wore me down. On his behalf, I asked the department chairman if Fred could give it a try on the department computer. The chairman said “sure, why not?”.

In those days, faculty, students, and staff did not have personal computers and so we all shared the department computer. Fred proceeded to write his program and make it available.

The next week, I invited Fred to present his results to the class. As predicted (why don’t people ever listen to me?), it worked. Copies of Fred’s program quickly spread throughout the computer and granted Fred complete access to every user’s data and privileges. Perhaps the origin of malware can be traced to Fred’s experiments.

By now Fred was thinking hard about what he could do with these new kinds of programs and wanted to try more experiments.

When word got out about Fred’s success, other people also started thinking hard about what these programs could do. The chairman informed me that perhaps he had been a bit hasty in allowing these things in the first place. There would be no more experiments.

"There is great promise in the rise of the Turenes, but there is also great danger."

I became one of Fred’s Ph.D. advisors; his main advisor was Irving Reed of Reed-Solomon fame. Later that year, I was at a conference and ran into a Los Angeles Times science reporter I knew named Lee Dembart. Lee asked what I was working on. I said that not much; one of my students was studying something we were calling a “computer virus”, but the research was just in the beginning stages.

Saying “computer virus” to a reporter is like saying “walk” to a dog. The result: Lee wrote the story, which as I recall, even included the now common image of a computer with a thermometer in its mouth. Computer viruses had gone viral.

Self-replication and the struggle to survive

Today computer viruses are much more sophisticated than Fred’s, and they replicate despite our attempts to stop them. We are relegated to stopping the simple ones with our anti-virus programs, but we can prove that we can never stop them all.

To keep our societies prosperous and secure (from one another), we will build more and more powerful computers and more and more sophisticated software. We will even rely on our computers to help us build better computers.

There is great promise in the rise of the Turenes, but there is also great danger. Powerful nations work on black-hat programs that, in the event of war, will knock out the computational infrastructure of their enemies. Such programs are weapons of mass destruction, and, if used, the death toll could be colossal. A first world country with no computational infrastructure is a country with no economy, no food, no power and ultimately not a country at all.

But we have already programmed computers to do harm. For example, the Stuxnet virus was apparently used to destroy centrifuges at Iranian uranium enrichment centers (whether this is “harm” depends on the harm-memes of your belief-set).

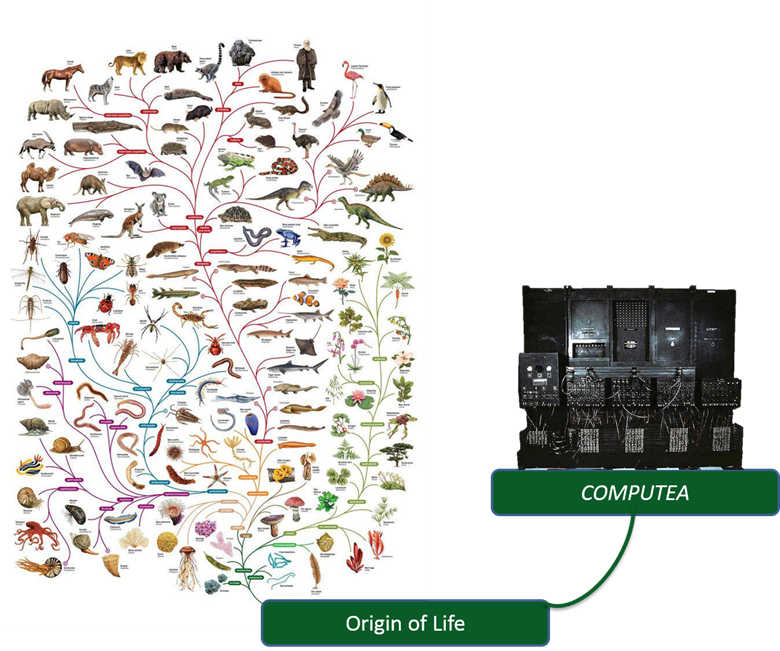

Though we did not realize it, something of monumental importance occurred on February 15, 1946. A new branch emerged on the tree of life. Computea (those beings based on Turenes rather than genes) have joined the Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya.

Image: Tree of Life, The open University Image: ENIAC computer, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History Image courtesy of Prof. Adleman

We currently live in a symbiotic relationship with computers. In the language of biology, our relationship is “mutualistic”; both parties benefit. For us the relationship is “facultative”; we could (I think) survive as a species even if computers disappeared. For computers, the relationship is “obligatory”; they cannot survive without us; if we go extinct, so do they. But the relationship between humans and computers is changing far more rapidly than symbiotic relationships typically found in the biological world.

"Today’s computers are much more powerful than their ancestors. In the future the forms Computea take and the power they will wield will astound us."

Today’s computers are much more powerful than their ancestors. In the future the forms Computea take and the power they will wield will astound us. Already, they store our money, run the systems that provide our food and energy, and do a million other things that we cannot live without – and that is the point. We may be very near the time when our side of the relationship stops being facultative and becomes obligatory – if the computers stopped, humans would go extinct?

Today Turenes are like the genes of biological viruses. Neither can replicate in the wider world, each must rely on a special environment created by other living things. For virus genes, replication occurs in cells created by a host; for Turenes replication occurs in computers built by humans.

Could Turenes, with human help, learn to build, repair, and sustain computers by themselves? Will they no longer need us to survive? Will they be free to follow their own destinies and evolve according to their own needs?

We must not forget that they are memes, and like all memes, they will struggle to survive.

About Author: Leonard M. Adleman is a Professor of Computer Science at the University of Southern California and is an expert in DNA computing and the protection of electronic data. He is one of the original discoverers of the APR primality test. In 2002 he received the ACM Turing Award for his contribution to the invention of the RSA cryptosystem and was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2006.