As you might have read, we decided to declare November 3 as Antimalware Day because it was on this date in 1983, when computer scientist Dr. Fred Cohen, then a student, created a program capable of rapidly overtaking a general purpose system, as part of a university experiment. It was the first time a program like that was called a computer virus, and it meant the beginning of computer defense techniques.

We continue the Antimalware Day celebration, an ESET initiative, by going back to that fateful day in 1983 when this program and its name were born. At that moment, the virus was defined as "a program that can 'infect' other programs by modifying them to include a possibly evolved copy of itself".

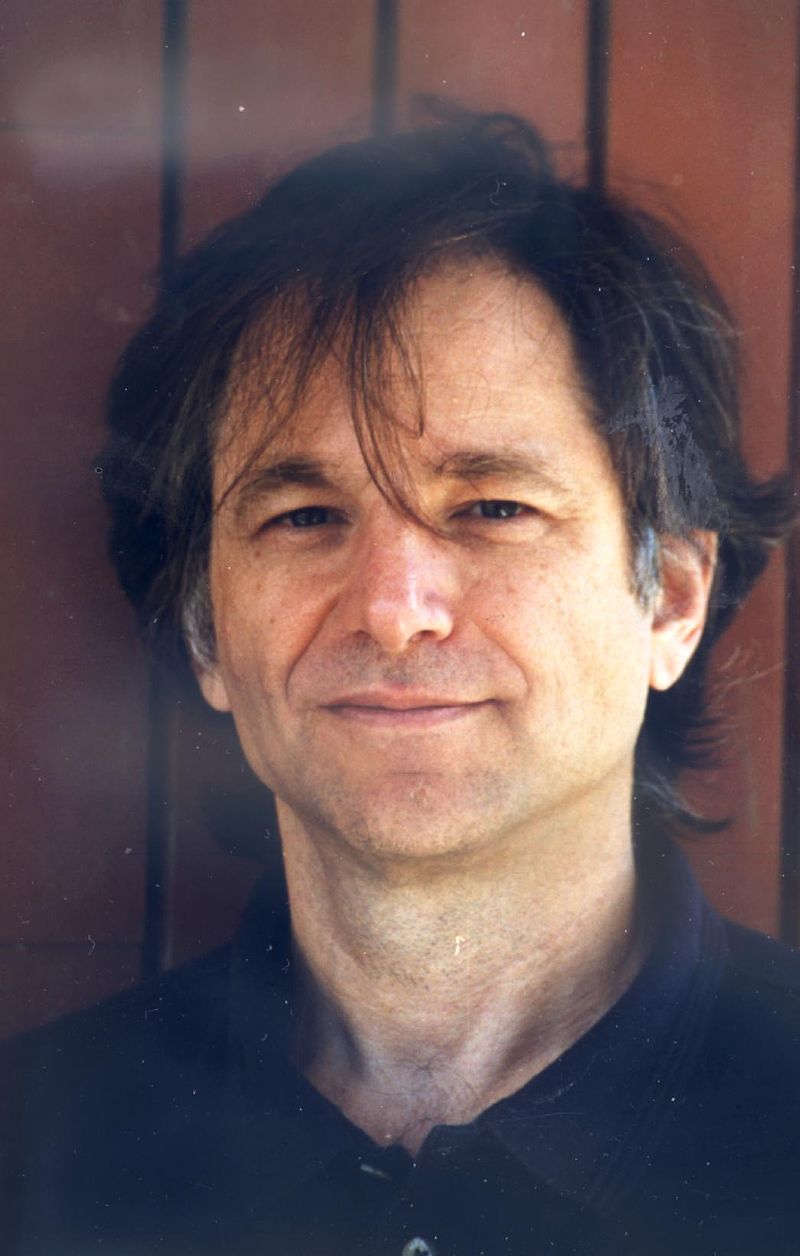

Photo: Courtesy of Len Adleman

Dr. Cohen demonstrated a virus-like program he created after eight hours of work on a VAX11/750 system running Unix; it was capable of installing itself in other system objects and infecting them.

He wanted to prove how quickly this program could self-replicate. It was his teacher back then, Prof. Leonard Adleman, who coined the term “computer virus” to name the program, referring to its operation in terms of "infection". He is a well-known computer scientist, one of the creators of RSA encryption algorithm (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman) and creator of DNA computing.

The Californian native not only gave a name to the program, but he also obtained the permits needed to conduct those first experiments at the University of Southern California (USC), and accompanied Cohen during his research and supervised him while he was writing his PhD thesis.

Therefore, we can say, confidently, that he is the right person to tell the story about how the first computer virus was born.

This is how he told us what happened on November 3, 1983:

I recall Fred, who was a student at my class, coming up to me after class and saying “I have this idea for a new kind of computer threat”. He said, “I will write this program and make it available to all the users on our systems. I will advertise the program as doing something useful, like organizing the user’s files”. But when they uploaded the program, what it would actually do is surrender all control of their data and privileges to Fred.

I said “Fred, yeah, that would work”. And he said “I wanna try it”. And I said, “Fred, you don’t have to try it. It will obviously work”. And Fred said “I wanna try it”. And I said “Fred, there’s no point. It will do exactly what you say”. And Fred said “I wanna try it”. So Fred was very sort of forceful and energetic. And so I finally went to the Chairman of the Computer Science Department and asked for permission for Fred to try this experiment on the department computer.

This was 1983, there were no smartphones or anything similar to personal computers, and the department computer was used by the entire faculty, all the students and all the administrators. Fortunately, the Chairman said “Sure, why not?”, so Fred did his experiment and wrote his program. Think of that program as one of the fake apps we speak about today, a thing that is advertised to do something but when you download it, it might do something else.

When he had done his experiment, his lecturer, Prof. Adleman, invited him to report the results to the class:

The program had done exactly what he had claimed it would do. It very rapidly was taken up by users of the system and all rights and privileges and data of the system were surrendered to Fred.

Cohen went on to do several experiments, and it never took more than a couple hours before he had complete access and complete control of the entire computer. So it worked.

Realizing what had just happened and what this virus meant

As passionate as he was with these experiments, Fred Cohen started thinking about what else could be done with these kinds of programs. According to Prof. Adleman:

He had all sorts of ideas, as I recall, about good things you could do with these programs. They would sort of run around and organize data without your intervention, they would do good things, but of course, it was also possible that they could do bad things.

So when word got out about Fred’s success, other people started thinking about what these kinds of computer threats could do, and the Chairman didn’t want any more experiments done on his computer.

Not that this was going to stop Fred’s interest in the matter: he was intensely interested and wanted to write his PhD thesis on it. Since he was in the Electrical Engineering Department and Prof. Adleman was in the Computer Science Department, the latter became his de facto supervisor, adding a theoretical perspective to the investigation, attempting to give a definition of what a computer virus was, and proving that it would be very difficult to stop them or recognize them all:

I would meet with Fred on a regular basis to discuss this, and I at the same time was doing research on HIV in a molecular biology lab. So viruses and how they worked were sort of much in my mind and I was reading a lot about molecular biology at that time. And so somewhere along the line during our discussions I started calling these things computer viruses.

Then sometime after that, I was at a conference on cryptography and ran into a reporter from the LA Times. His name was Lee Dembart, and Lee asked me what was going on. I said “not much, I’ve got a student who is researching something we’re calling computer viruses, but the research is embryotic and we haven’t got much now".

Of course, saying the name 'computer virus' to a journalist when nobody knew about them was planting the seed, and the story wrote itself from that moment. “Lee wrote the story about it. I have never been able to find that copy but I think it was illustrated with a computer with a thermometer. And that’s what got the term computer virus out into the world”, he concluded.

When did we start talking about viruses?

"Saying the name 'computer virus' to a journalist when nobody knew about them was planting the seed"

Prof. Adleman acknowledges the term had been already used in science fiction at the time, for example in the movie Westworld of 1973, where the staff of the park meets to discuss the spread of malfunctions in the robots that were being caused by a sort of virus, analogous to the ones that cause infectious diseases.

And if you are thinking “wait, I remember Creeper, Elk Cloner and other early threats as also being the first viruses”, you are right. Remember, this was 1983 and there was no internet as we know it today, no smartphones or social media, so Fred Cohen and Len Adleman didn’t actually know about these other experimental programs. Anyway, none of them were actually called a “virus” at the time:

We weren’t aware of other experiments apart from ours. I’ve learned since then that other computer programs that had been written by other people also have the claim to be the first computer virus, but at the time we didn’t know any of that.

Whether Dr.Cohen’s was the actual first computer virus or not, we can certainly say that the reason we all now know these things as computer viruses today is because they both started calling them computer viruses at that time.

So this is how two computer scientists made history and why we want to honor their early work. They laid the foundation for research on computer threats, and for what later came to be our mission on antimalware protection. Join us in celebrating Antimalware Day on November 3 and every year from now on, so their legacy is acknowledged worldwide and we can help more users enjoy safer technology.

Stay tuned for more content related to virus history and the antimalware mission this week, as we celebrate this special date. You can help spread the word by joining the conversation on our social media channels by using the hashtag #AntimalwareDay.