Just as attackers are finding new, increasingly sophisticated ways to try and evade the detection techniques used by antiviruses, they are also improving their methods designed to trick the user or at least evade the main techniques that tend to be taught in standard IT security training.

Despite this, we can always take another step forward to strengthen our security and detect the tactics they are using, as we will see in this article.

Firstly, they have dramatically improved the design of phishing scams, using convincing images or the inclusion of iframes whose content is pulled in from an authentic page.

Also, thanks to the advantages of today’s online dictionaries and translators, they now manage to avoid (some) grammar and spelling errors in their emails.

Furthermore, it is no longer enough to look at the address of the sender of an email or SMS, because thanks to spoofing techniques, an attacker is able to pass for a different entity by falsifying data in a message.

It is also necessary to pay special attention to the links that scam emails redirect to because often the fraudulent sites are hidden behind shortened or compound addresses, so as not to reveal their intent at first glance.

Even so, we still had one piece of advice that, until now, we thought to be infallible: check the page is secure, that it uses HTTPS protocol and, above all, that it has the security certificate.

Cybercriminals with secure websites

While it is true that most fraudulent web pages use HTTP, whereas original sites requesting credentials (like social networks, bank portals, etc.) do so through HTTPS, this does not mean attackers cannot do the same. In fact, they can easily convert their site into HTTPS, obtaining a completely valid SSL/TLS certificate for it – and free, for that matter.

For this to work, the attacker would need to be capable of registering a domain that looks as similar as possible to the real website that they are looking to fake, and then obtain the certificate for this new domain. One option is to look for domains that are written in a similar way. For example, “twiitter.com” versus the original “twitter.com,” or “rnercadolibre.com” versus the original “mercadolibre.com.”

Remember those experiments where they show you incomplete words or words with almost imperceptible errors, and how when you read them quickly it’s just as though they were complete and correct? Well, the same thing happens to a lot of people with URLs when they are browsing.

At first glance, if you are reading quickly, these examples could trick quite a few people, but you only need to look closely at how the address is written in order to detect the trick. What the attacker needs is to be able to register a site where the address is written differently, but looks the same to the user, and that is why homograph attacks are used.

Let’s look at an example. Can you tell whether this site is fake or not?

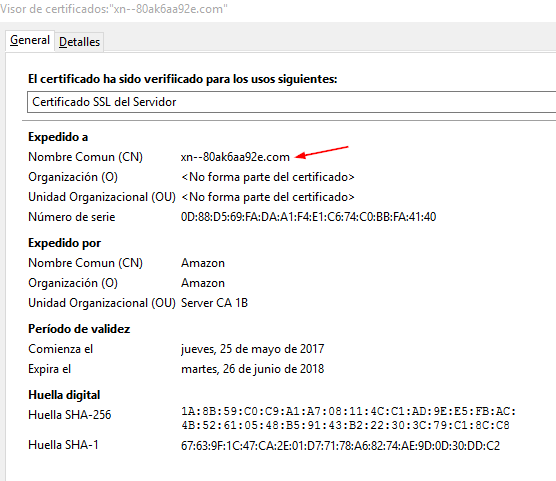

This example is a part of a proof of concept carried out by the researcher Xudong Zheng, who registered the domain https://www.xn--80ak6aa92e.com/. You can see how it works by visiting the link through the Firefox browser.

What makes it possible is the use of Unicode characters from non-Latin writing systems, like Cyrillic or Greek. In these alphabets we can find characters that are similar, or even identical to those we use in the Latin alphabet and in URLs. Thanks to Punycode, which is a coding syntax that allows any Unicode character to be translated into a more limited string of characters that is compatible with URLs, a domain using these characters can be registered.

For example, it is possible to register a domain name such as “xn--pple-43d.com,” which is interpreted by the browser as “apple.com,” but is actually written using the Cyrillic character “а” (U+0430) instead of the ASCII “a” (U+0041). While both characters look the same to the naked eye, for the purpose of browsers and security certificates these are two different characters, and so represent different domains.

There are numerous examples, like “tωitter.com” (xn--titter-i2e.com in Punycode) and “gmạil.com” (xn--gmil-6q5a.com). You can even have fun creating your own combinations with a Unicode to Punycode converter.

Many current browsers have systems that try to prevent these types of attacks. For instance, in Firefox or Chrome, if a domain contains characters from different writing systems, rather than showing its Unicode form, they show the corresponding Punycode.

So, in the previous examples, instead of seeing “apple.com” (Unicode form), we would see “xn--pple-43d.com” (Punycode form), while “tωitter.com” would be “xn--titter-i2e.com.”

Nevertheless, in the proof of concept, Xudong Zheng manages to sidestep this protection by registering the domain “apple.com” using only characters from the Cyrillic alphabet. This way, “xn--80ak6aa92e.com” looks like аррӏе.com.

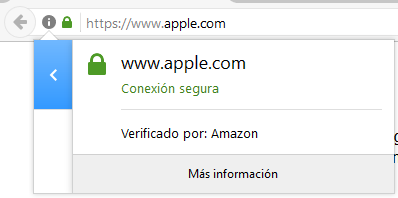

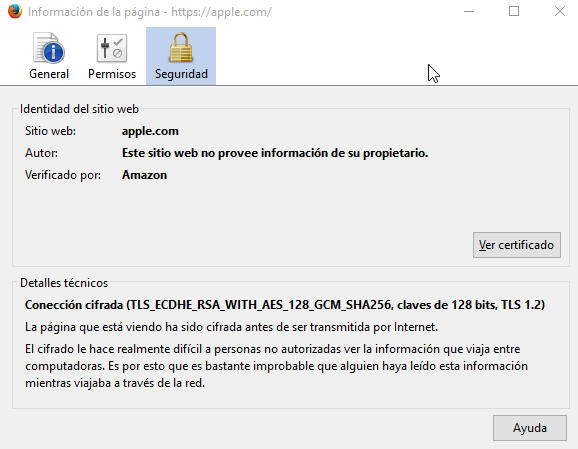

The researcher also went one step further, using Amazon to obtain a TLS certificate for his domain, which at first glance is quite convincing:

But if we go in and look at the details, we can see that it actually belongs to “xn--80ak6aa92e.com:”

While this vulnerability has now been corrected in the latest versions of Chrome and Internet Explorer, other browsers like Firefox still suffer from this problem. An alternative in Firefox is to set the option network.IDN_show_punycode as true, so that it always shows characters in their Punycode form.

Even so, the gmạil.com site from the previous example also manages to evade Chrome’s protection, as it only uses Latin characters, but includes a special Latin character (“ạ”—note the dot below the "a"), which is displayed by the browser.

Protection needs to be reinforced

Each time we find a new case of phishing or some fake page aimed at tricking the user, we repeat the advice: check the sender of the message, pay attention to the link of the page you are taken to, ensure it is written correctly and, above all, that it is secure (i.e. uses HTTPS) and has a security certificate.

However, these precautions are no longer enough, because cybercriminals are using increasingly complex techniques to trick the user. Using HTTPS and certificates isn’t a security consideration on the part of the attacker; after all, if they’re stealing your credentials, what do they care whether they are encrypted or not?

The point is that these techniques are employed in order to give users a false sense of security, which leads them to enter their data in the belief that it is a secure site, having followed the advice repeated to them ad nauseam that they should look at whether the site has a little padlock and says HTTPS. As we have seen, though, this is no longer sufficient.

For this reason, as well as paying close attention to emails and websites, we also recommend that you look carefully at the security certificates, avoid accessing websites through links sent in emails (it is better to do so always by typing the URL or through trustworthy direct links), and add an extra layer of protection to your accounts by using two factor authentication.