On the air

While a sizeable proportion of my income still comes from writing about security, I do very little media stuff nowadays. I've no current plans to do another conference presentation, and I can’t remember the last time I did a live interview, let alone a radio interview. However, there was a major exception in November 2016, when I talked to an audience whose location is so remote, it makes my little corner of West Penwith – that's the bit right at the western end of Cornwall in the UK – look like Gotham.

I was invited to do an interview with Craig Williams – who has a company called Gigabyte IT – on Saint FM. That’s a community radio station on St. Helena, an island way down in the South Atlantic where Napoleon Bonaparte spent the last six years of his life, and which has only recently started to benefit from the mixed blessing of the mobile phone. He (Craig, not Napoleon) came across me via an article to which I contributed some internet safety tips for parents and children a while ago. And by the miracle of internet technology I was able to take part in the interview at the same time* as I was in Shropshire preparing for a musical event.

Parenting and the internet

While I would encourage anyone interested to read that article on internet security, in which many other people also offered tips, perhaps I should simply mention here that my main argument was that parents should regard themselves as educationalists and recognize that it is never too early to help their children to develop rational and critical thinking about what they see on the internet and learn to trust their own judgment.

Anyway, here are the questions Craig asked me, and a (slightly modified) transcript of my responses. I found the third question particularly interesting: it's not often you get to talk to people in a state of transition between the landline/telephone kiosk and the smartphone.

- What advice would you give to parents about their child being safe online?

If your child knows more about technology than you do, it doesn't mean that they're better at personal security than you are. Children and teenagers are often quite blasé about the risks of technology, having grown up with it on tap, as it were. But they don't have the life experience that you do. Even tech-savvy adults are often naïve about what they read online, whether it's a matter of falling for scams or spreading hoaxes. We often hear that old people are most at risk on the internet, but in fact they are sometimes better able to extrapolate from their experience of the pre-internet world to the online world.

"It's part of your responsibility as a parent to learn enough about security issues to educate your child, and in the 21st century that includes cybersecurity."

It's part of your responsibility as a parent to learn enough about security issues to educate your child, and in the 21st century that includes cybersecurity. Of course, most people want to protect their children from the start, but it's just as important to help them to protect themselves when you're not there. And it's never too early to start the process.

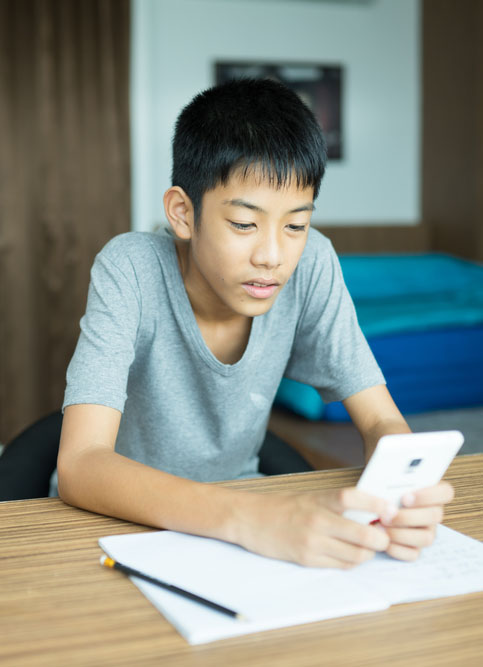

Of course, the age at which children are first exposed to the online world has plunged in recent years. But it's also a good idea to instill a sense of caution before they're old enough to think that they know more than you do.

In the meantime, don't be afraid to take control by restricting their access. That's much more difficult to do across the board than it used to be, but it's still possible on a shared family PC, for instance. But explain why you're doing it: after all, it's not them you don't trust – it's the bad people out there.

- As a professional security expert, what advice would you give to children about having an online presence?

"People you meet and talk to online aren't always who they say they are: it's very easy to pretend to be someone you're not."

People you meet and talk to online aren't always who they say they are: it's very easy to pretend to be someone you're not. In social media, for instance, often there are no checks worth mentioning: it may be just a matter of registering with false information.

For example, some days after the interview, my friend and colleague Urban Schrott drew to my attention an article in The Irish Sun in which it was claimed that an app described as 'Tinder for teens' made no attempt to validate a new subscriber's identity or age. Urban commented "Any app, even if just a game, intended for under-age children, which allows direct interaction with other users, will automatically attract the attention of online predators, privacy violators and cyberbullies."

It's also easy sometimes to take control of an account that rightly belongs to someone else so that you can pretend to be them. A service should be looking after your information, but that doesn't mean it always does so effectively.

It isn't much consolation if harm is done to you and it's Facebook's fault, or Twitter's, or WhatsApp’s, rather than your own.

You should never assume that everything you read on the internet is true, even if it's written or passed on by someone you trust. A lot of people pass on something they read without checking facts, because what they read agreed with their own views and expectations.

(Of course, I'd probably express it a little more simply if I was talking to very young people. And in the same way, when I used to talk to teenagers at secondary schools who were working towards their GCSE** exams in Information Technology, I would talk more technically, even if I didn't assume that they had the same understanding as a computer science graduate.)

- For an island of around 4,000 people, and with mobile access only made available earlier this year, what would you say needs to be put in place for kids, to fight against cyberbullying and online grooming?

Four thousand or so people is quite a large enough number for unpleasantness and exploitation to take place without the knowledge of the authorities and other responsible adults. My first mobile phone wasn't even capable of sending and receiving texts, but I guess you've jumped straight into the era of the smartphone, which is as much about internet connectivity as it is about phone calls and SMS messaging.

Four thousand or so people is quite a large enough number for unpleasantness and exploitation to take place without the knowledge of the authorities and other responsible adults. My first mobile phone wasn't even capable of sending and receiving texts, but I guess you've jumped straight into the era of the smartphone, which is as much about internet connectivity as it is about phone calls and SMS messaging.

Children in the UK get their own phones very, very early nowadays, but maybe peer pressure is less of an issue on St. Helena so far. If so, perhaps it gives you time to think about how to deal with the sort of problems that go with juvenile telephony. On the other hand, the risks are far wider than theft and bullying by text now, because the internet functionality available on smartphones and tablets is almost equivalent to that available on desktop and laptop computers, bandwidth permitting.***

I'd suggest that St. Helena needs to ensure that there is a source of reliable information on issues such as cyberbullying, grooming, covert communication between pedophiles, and good practice in securing internet services and devices. And that information needs to be available to parents, teachers, and law enforcement, so that it can be passed on in a suitable form to potential victims.

Conclusion

Well, that last point is as true everywhere else in the world as it is on St. Helena. And none of the points I made here are entirely unique to the island. However, maybe the community there can learn something from the mistakes we've made in parts of the world where technology has progressed faster and further. Certainly Craig deserves credit for seeing the need for forward planning while the always-online world is in many respects still less pervasive in his community, and I hope my thoughts will have been of some small help.

*That's almost as impressive as being in Ensenada and in Echo Park at the same time.

**Schools on St. Helena are taught according to the English National Curriculum, adapted for local use.

***According to Wikipedia, the island is currently reliant on a single, overstretched and expensive satellite link for broadband.