Two thirds of American adults think that their government is not doing enough to catch and prosecute people who commit computer crimes. That's based on 775 survey responses gathered in a three day period last month (more details below). Which is not to say that the federal government isn't doing anything. Later in this article I will mention some of the good things that the government is doing, and some of the things that we, as good citizens, can do to help.

Cybercrime as a priority?

First let me be clear on one thing: I'm not implying that the people who do the catching and prosecuting of cyber criminals are slacking off. Heck no! I've met plenty of "feds" who work all hours of the day and night investigating cyber crimes, and it's my considered opinion that without their efforts the cybercrime wave would be much worse than it is. The problem is, we need a lot more of these dedicated cybercrime fighters, paid at competitive rates, equipped with the latest tools. Sadly, I don't think we're going to get them, not until cybercrime is elevated from being "a law enforcement priority" to "the law enforcement priority."

Regrettably, history has not been on side of cybercrime fighting. Speaking to the National Press Club on June 20, 2003, Robert S. Mueller, III, then Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), said, "After counterterrorism and counterintelligence, cyber crime is our next priority." Unfortunately, being second didn't equate to crushing cybercrime in its nascent stages. In the years that followed it flourished, and then financial fraud on a massive scale shot up the public agenda. That diverted attention and resources from cybercrime. In recent years cybercrime has received renewed focus, but fears of terrorism keep it from the top spot.

The US Department of Justice (DoJ), which includes the FBI, is headed by the attorney general. Her highest priorities were recently stated as: "safeguarding our national security, identifying and pursuing cyber threat actors, strengthening relationships with the communities we serve, protecting the most vulnerable among us and ensuring that we hold lawbreakers accountable regardless of whether they commit their crimes on the street corner or in the boardroom." So, white collar crime down, cybercrime up, but you have to wonder: Why isn't "identifying and pursuing cyber threat actors" part of safeguarding our national security?

All of which adds up to one of the main reasons that cybersecurity research can be a very frustrating line of work: You spend years telling anyone who will listen that if we don't mount a suitable response now, cybercrime is going to get a lot worse; then you spend years documenting all the ways in which it is getting worse; until at some point you lose your voice and nobody can hear you hoarsely whispering, "Cybercrime is now an existential threat to our nation."

Cybercrime age concern?

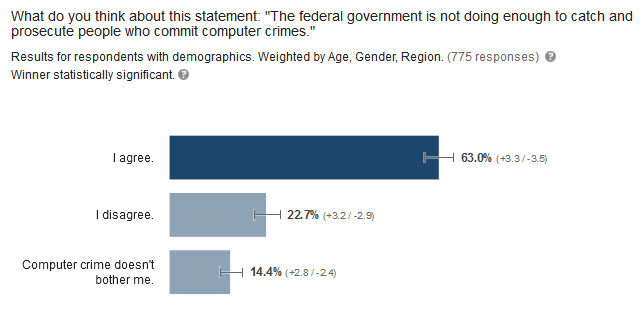

Of course, you wouldn't be in security if you didn't have at least half a glass of optimism in you, so you take heart when you see signs that your message might be getting through to the public. Like when our survey found nearly two thirds can see that the federal government is not doing enough about computer crime. Here's what those survey results look like, as generated by Google Consumer Surveys:

This gives me hope! Hope that we really can call on people to call on their elected representatives and tell them to quit talking about this problem and starting funding the solutions (hey, it's an election year!).

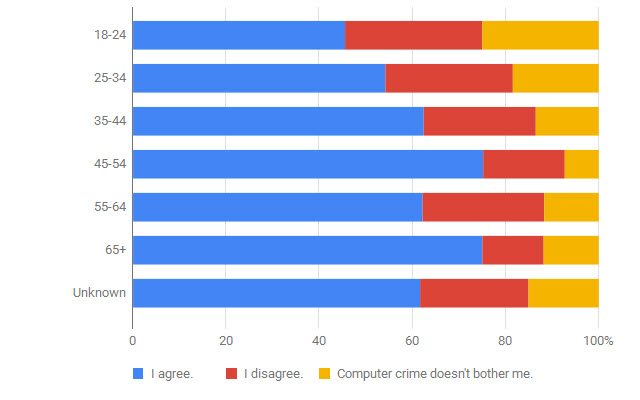

However, as a security professional I can't afford to be too optimistic. And as a security researcher I needed to look at the demographic breakdown of these responses to make sure I understood what this survey was telling me. Unfortunately, it tells me this: Young people don't see things quite the same. Notice that about 25% of the 18-24 bracket say they are not bothered by computer crime.

Why would people under 25 not be bothered about computer crime? That's a great research topic right there, but until someone does that study we can only speculate. One hypothesis: younger people don't bear the brunt of cybercrime to the same extent as older folks (who have families to support and companies to run). Of course, for a "senior" researcher to suggest such a hypothesis might be reverse ageism, I don't know.

What I do know is that an ESET survey about ransomware in March found that people under 25 were less aware of this particularly nasty form of cybercrime than older folks (34% of millennials said they didn't know what ransomware was, versus 30% of the general population). Another hypothesis, that younger people think they are better protected against cyber criminals than their elders, is countered by ESET's findings about data backup habits. While it's worrying to me that 31% of the general population said that they never back up their data, that number rises to 35% among those identified as being under 25.

When I looked around for other indicators of age differentials in cybersecurity I spotted a survey from SecureAuth Corporation, done in conjunction with Wakefield, and looking at "internet speed versus personal security and online behavior over public Wi-Fi." The results indicate that Americans in general would choose better personal online security (57%) over greater internet speed (43%). But more than half of millennials (54%) would rather improve their access speed than their personal online security. Underlining this age gap is the finding that, when it comes to public Wi-Fi, the percentage of American adults who said they had given out some sort of personal information online over public Wi-Fi was 57% but that "jumps to 78% among millennials."

But what can we do?

The above findings notwithstanding, there's one question that I've been asked by people of all ages: what we can do to reduce cybercrime? There used to be two parts to my answer and in the short version they used to go like this:

1. Increase the cost to criminals of committing cybercrime by following good cyber hygiene.

2. Implore your elected representatives to put more emphasis on, and resources into, cybercrime deterrence (identifying, apprehending, and prosecuting the perpetrators).

Recently I have added a third part:

3. Report all cybercrimes to law enforcement, because law enforcement has a hard time demanding resources to deal with crimes that haven't been counted.

I realize there may be some push back on this, like "even if you report it, they don't do anything, so what's the point?" So allow me to explain why I added that third point. A few months ago I heard a very interesting talk by the Honorable John P. Carlin, Assistant Attorney General for National Security, the person who serves as the Department of Justice’s top national security attorney. Carlin oversees the work of the National Security Cyber Specialist Network. He investigated the 2014 Sony Pictures Entertainment hack and brought the first indictment against members of the Chinese military for economic/cyber espionage.

Carlin also launched a nationwide outreach effort across industries to "raise awareness of national security cyber and espionage threats against American companies and to encourage greater C-suite involvement in corporate cyber security matters." The talk that I attended was part of this outreach and I came away with two reasons why we should all report cybercrime. First, there's the need for law enforcement to document how widespread cybercrime is so that they can make a better pitch for more resources.

(As I documented at Virus Bulletin 2015, the folks in the federal government who are not actively involved in fighting crime have ceded to the private sector the responsibility to research cybercrime; but cybercrime statistics produced by companies that offer cybersecurity products and services are too easily dismissed as marketing material by politicians who are reluctant to fund law enforcement at requisite levels.)

The second good reason for reporting cybercrime is that it might help catch the bad guys (and those bad guys might be really bad). As the FBI accumulates reports from people and companies that have been hacked it can look for patterns and trends and "connect the dots." Consider a scenario in which a small business gets hacked and personally identifiable formation is stolen. The firm decides to report this to the FBI, which then makes some connections, which eventually expose an ISIL terrorism connection. The result? A cyber criminal is arrested in Malaysia on US charges. And that's a true story.

So yes, the federal government should be doing a lot more to fight cybercrime. But there's no need to tell that to the law enforcement folks who are doing the best they can with the resources they've got. They are getting some good results. Now we have to tell Washington we need more of them.