In 2007, Andrew Lee and I presented a paper at Virus Bulletin on *Phish Phodder: Is User Education Helping Or Hindering? While the paper is not only about phishing quizzes, we were concerned at the time that of the many quizzes being touted at the time for their supposed educational value. These included multiple-choice questionnaires aimed at raising consciousness about phishing issues, but we focused mainly on

‘Email or website recognition tests where the participant assesses whether sample messages or (less often) sites are genuine.’

We noted that:

‘These are … of highly variable quality. Sometimes the testing site’s own analysis of ‘suspicious’ attributes is inadequate or misleading.’

For quite a while now, I’ve been thinking that it would be interesting and possibly even useful to take another look at phishing quizzes, but I haven’t found time yet for a wide-ranging research project. However, when I came across a blog article on 97% Of People Globally Unable to Correctly Identify Phishing Emails: Intel Security I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to look at the data and therefore at the quiz that had been the means of generating the data.

If three of the 10 mails offered are legitimate, that suggests that 17% of a population of security professionals were taken in by at least two phishing emails97%? That’s pretty bad, right? Well, it could certainly be better, but it’s not quite as bad as it looks. Intel’s phishing quiz got responses from 19,458 people from 144 countries, and while only 3% of respondents identified all ten email samples correctly as either phish or as genuine messages from the apparent sender (three out of the ten samples were legitimate), it’s not as though the other 97% failed to identify any phish, though apparently 80% failed to recognize at least one phishing email. On the other hand, it appears that the email most often misidentified was actually an innocent email mistaken for a phish. (Hold that thought!)

Intel circulated a version of the quiz to 100 attendees at RSA last year.

On average, industry insiders were only able to pick out two-thirds of the fakes. A slim six percent of quiz-takers got all the questions right, and 17 percent got half or more wrong. Remember, this is their job.

Unfortunately I don’t have access to the raw data so I have only the figures reported by various journalists, but if three of the 10 mails offered are legitimate, that suggests that 17% of a population of security professionals were taken in by at least two phishing emails, but at least the percentage of respondents who got all the questions right doubled.

Here’s an extract from that paper with Andrew Lee:

Informal discussion with an arbitrary sample of other security professionals suggests that they generally:

- Pick up all the real phishes

- Correctly assess some mails as legitimate

- “Fail” to recognize some legitimate mails as such. We believe that this often results because, lacking sufficient contextual information to assess their legitimacy, they err on the side of caution.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that even the general public score better on phish recognition than they do on legitimate but phish-like mails. But is that their problem, or that of the institution that sends out phish-like emails?

Some figures have been published suggesting that age and gender differences affect susceptibility to phishingThe CBS News article includes this link to the quiz, if you’d like to give it a go. The quiz includes an optional form for entering details of gender, age, where you live and on what device you primarily read email. I have no idea how many respondents actually completed the form, but for those that did, some figures have been published suggesting that age and gender differences affect susceptibility to phishing. Well, that’s not surprising. However, the Cybersquad article tells us, for instance, that

On the whole, men gave slightly more correct answers than women, averaging a 67% accuracy rate versus a 63% rate for women.

Other research differs (which doesn’t tell us which view is correct – if either). As I said in that 2013 blog:

I don’t know whether men are generally better than women at recognizing phish. Anecdotally, though, my (looooonnnnnggggg) experience of user support and of talking to students – Teach Your Children Well – ICT Security and the Younger Generation – in Europe and the UK suggests that females may be less susceptible to phishing attacks because they’re less likely to rely on their own self-perceived expertise and more likely to ask for advice from someone perceived to be more knowledgeable.

Similarly, a recent poll commissioned on behalf of ESET Ireland actually suggested that women in Ireland are more cautious when it comes to security than their male counterparts (age also seems to play a large part). Of course, self-assessment of security awareness and capability can, as this study suggests, be very different from the picture painted by objective testing. It depends, of course, on how good the testing is.

The Intel and North Carolina State University studies seem to agree in several respects, perhaps suggesting the importance of regional differences. It’s certainly noticeable that according to the Intel data, European nationals seem to be better at recognizing phish than USians:

Of the 144 countries represented in the survey, the U.S. ranked 27 overall in ability to detect phishing, with 68% accuracy. The five best performing countries were France (1), Sweden (2), Hungary (3), the Netherlands (4), and Spain (5).

The earlier study showed similarly depressing results, though it’s not really feasible to compare the data directly:

Overall, people performed badly. Although 89% of the participants said they were confident in their ability to identify malicious e-mails, 92% of them misclassified phishing e-mails.

52% of participants misclassified more than half the phishing e-mails, and 54% deleted at least one authentic e-mail.

Quizzes normally use screen shots, not actual emails. Thus, the information that we’d use to investigate further if we had access to the email wasn’t available.But how far can we trust quizzes like this? In our Phish Phodder paper, one of the problems we found with quizzes was that even security professionals were not always able to classify a message correctly, because quizzes normally use screen shots, not actual emails. Thus, the information that we’d use to investigate further if we had access to the email wasn’t available. In this eventuality, a security professional will normally play safe and assume malice.

As it happens, the quality of the Intel quiz is higher than that of most of the quizzes we looked at in 2007, but it’s worth looking at some of the issues we found, as there are still quite a few older quizzes out there, and it’s worth thinking about what they do and don’t do well.

- Some quizzes are based on the assumption the participant can make an accurate assessment, irrespective of the legitimacy of the mail, simply by viewing a screenshot. Some quizzes, though, don’t indicate whether embedded URLs were exactly as shown, obfuscated, or otherwise deceptive – as when the apparent and real target link are quite different. Thus, the subject loses the advantage of an important visual cue for identifying some kinds of phish.

- The use of static screenshots deprives the subject of other visual cues such as access to HTML source code, and rarely explicitly address heuristics – “Do I have a business relationship with the apparent sender of this message?”; “Was this sent to the address that I reserve for this account?” – that contextual information may be key to the individual recipient.

- Quizzes don’t usually support the use of tools like whois to check the bona fides of a referenced site.

- There are many techniques for misdirection to a malicious site (URL obfuscation, typosquatting etc) that echo poor practice by legitimate sites (secondary domains, outsourced web pages, tinyURLs, overlength URLS): these tend to be difficult to represent properly in a static screenshot, but all too commonly found in real phish.

But let’s go back to that thought about misidentifying an innocent email. Sometimes, correctly categorizing a phish as innocent or malicious is a bit like one of those TV shows where you know who the murderer is because it’s always the first person the cops interviewed but believed their story. It’s about second guessing the scriptwriter – er, quizzer – not about being forensic- or security-literate. It’s about evaluation based on incomplete data and withheld information. While quiz-derived data hardly ever goes into detail about the numbers of respondents who misdiagnose one or more ‘innocent’ messages, it seems to me that the “correct” answer in such a scenario is always to assume the worst.

Forgive me if I quote that paper again…

- Where legitimate institutions send emails that don't conform with best practice, they actually inadvertently groom the customer on behalf of the scammer. Quiz sites may prefer examples of such mails: mails that conform to good practice such as including the recipient’s name are probably easier to categorize, but “too easy to guess.” In the end, perhaps it’s a question of what point the quiz site is trying to make when it includes genuine mails. Of course, the site has to include some genuine mails, or it wouldn’t be much of a quiz, but that might mean that a quiz isn’t the best approach in this case.

- Alternatively, the site may be making the same point about customer grooming: however, it’s rare for a site to make this point explicit with reference to a quiz sample, perhaps because of a reluctance to offend the institution from which the sample mail was sent. If a poorly-formatted, de-personalized, phish-like message is used as an example of a genuine mail, it may be categorized as fake. When this happens, the participant is “penalized” or at any rate marked down for being suspicious of a mail that illustrates bad practice. Clearly, the “wrongness” in this instance should be ascribed to the provider, not to the person taking the quiz.

Another issue that worried us was that some quizzes simply mark you as right or wrong without further explanation.Another issue that worried us was that some quizzes simply mark you as right or wrong without further explanation. In our paper, we cited a “genuine” example with no obvious personalization, which offered no means of accessing the recipient’s account except through an embedded link, and carried the message “Please do not attempt to respond to this email” so beloved of phishmongers. The quizzer’s comment was to the effect that “You can only tell if this is legitimate if it’s an institution you have an account with and the situation they’re flagging is one you know applies to your account.” Helpful.

While even a poorly-designed quiz does at least raise awareness of the problem, that benefit may be outweighed if it reinforces misconceptions on the part of the participant, and even deprives them of the incentive to learn something about phish identification by encouraging them to use a product service supplied by the quizzer instead. If it’s a good product or service, maybe that’s not such a bad thing, but sometimes an alert message recipient can spot a phish that slipped past automated filtering, however good the service.

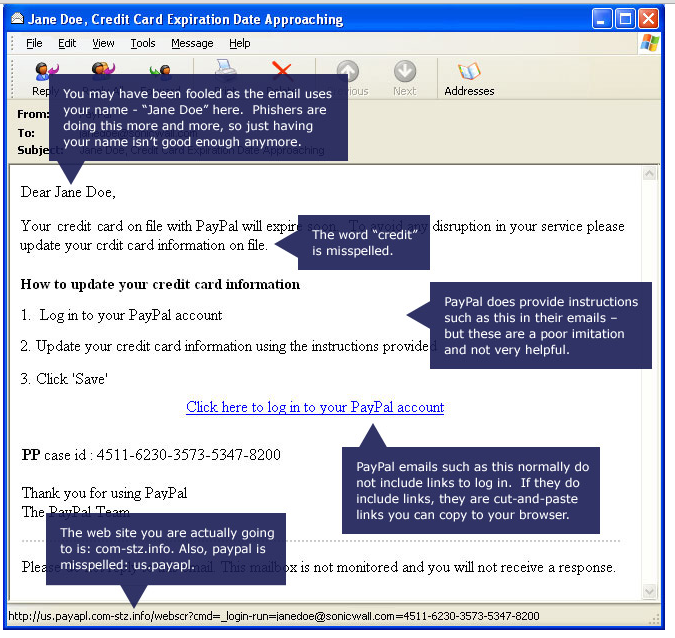

To be fair, some quizzes do actually explain in detail the danger signs to be found in their samples, as in this quiz from SonicWall.

As can be seen from this screenshot, it’s quite old (it’s actually related to one of the better quizzes we alluded to in that early paper), but a good example of how to do a useful phishing quiz:

As you can see from the second screenshot, the quiz really does offer useful information about what to look for in a phish email, related to specific examples.

The Intel quiz doesn’t offer information on the specific messages except whether your guess was or was not correct, but it does offer 7 Tips To Avoid Being Phished, though some of these are snippets of generic advice such as keeping security software up to date and browsers patched, and not clicking on messages from ‘unknown or suspicious’ senders. Still, it’s good advice, and some – such as the advice to check where a URL really points by hovering over the link with the mouse cursor is very much to the point, though the same tip quite rightly points out that it’s still better to avoid embedded links and navigate to a known legitimate URL. Furthermore, a slightly different link includes a nice little animation that includes five common indicators.

Believing that the best quizzes are those that leave the participant knowing more than they did before the quiz, we included in the paper some heuristics and suggestions of which I’ve made frequent use subsequently, but I don’t have a problem in summarizing them again here.

- Distrust messages asking for sensitive information – and this includes requiring you to enter login credentials – apparently from people with whom you don’t have a pre-existing business relationship.

- Use a specific email address for internet transactions that you don’t use for other sites: discard mail apparently from the same site sent to other addresses.

- Phishers try to panic you with an urgent instruction (“You must log in within 24 hours or your account will be terminated”) into responding recklessly and inappropriately.

- Requests for sensitive data (credit card numbers, account details, Social Security Numbers, PINs) sent by email and channelled through direct web links are either malicious or bad practice.

- The more data requested, the more suspicious: these data amount to a substantial definition of financial/social identity, meaning that a scammer can use them to pretend to be you. However, an attacker can acquire byte-size lumps of apparently insignificant data over time to aggregate into a full-strength ID theft package.

- If someone or an organization you already deal with requires you to re-authenticate online from an embedded link, the message is either fraudulent or incompetent. Don’t trust embedded phone numbers either. Always use contact numbers and addresses known to be valid, and use the login procedures established when the account was set up.

- If you think you there is a reason to respond to the message, do so ‘out-of-band’: for example, go to the legitimate site directly (not following links from email), or contact the customer services department or local branch to verify that the message is authentic.

- Impersonal is suspicious, certainly in a message that expects you to act on an embedded link. Even a generic marketing message shouldn’t expect you to click on a link within the message: it’s not appropriate for organizations that hold sensitive data to encourage their users to follow links that could easily be fake or spoofed.

- “Dear Citibank customer” or “Dear fredbloggs@bigfoot.com” doesn’t qualify as personalized. Even “Dear John” or “Dear Donald Trump” isn’t prove personalization: there are many ways to find a name from an email address (even one that doesn’t include some form of your name), and sometimes the process can be automated. If another identifier is used (e.g. an account number or eBay registered name), check it’s correct, not just an identifier made up to look authentic. Multiple addressees, a generic mailing list addressee (e.g. “Client-list”) or no addressee (i.e. a blind copy) all suggest random/multiple mailings.

- Pidgin English or poor spelling is suspicious, but impeccable presentation doesn’t prove legitimacy.

- Look for trust indicators such as https:// and digital certificates, but don’t rely on them. In particular, padlock icons are not proof of authenticity.

Technical tricks – intended to evade standard detection technologies – such as image spam, hashbuster graphics or text, obfuscating text and tags, tricks with font colours and attributes, divergent URLs, persistent redirection and so on are a good indication of malice (or at the very least of spamminess). Some of these indicators, are of considerable use and interest to the security professional. However, the everyday user and quiz participant is far less likely to be able to recognize them or even look for them.

It’s not enough to point out to people that they guessed wrong.It’s also worth bearing in mind that while standard phishing messages usually appear to come from businesses, government agencies and so on, some kinds of phish – especially spear-phishing and other targeted attacks – may appear to come from friends, colleagues and other individuals you would normally trust. More often than not, the sender address will be spoofed. However, as the McAfee tips page points out:

With hundreds of millions of personal data records compromised through data breaches since 20051, you can't always guarantee that an email from someone you know is legitimate.

If you’re at all surprised at the content of a message from a friend or family member – such as the well-known ‘Londoning’ scam in which the ‘friend/family member’ claims to have been robbed and to be in need of urgent financial assistance in some far-flung corner of the universe – it’s a good idea to check with them by other means, for instance over the phone. Even if they did send it, it’s worth it being cautious about following links and opening attachments they send. I often say ‘Trusting the person doesn’t always mean you should trust the code.’

In spite of all these caveats, a well-designed phishing quiz can certainly help alert potential victims to commonly-used scammer tricks. But (to paraphrase Andrew Klein of SonicWall in an email discussion in 2007) it’s not enough to point out to people that they guessed wrong. You have to show them where to look for better indicators, and who they should blame for the bad practices that condition them to guess wrong. The trick is not only to raise awareness, but to encourage appropriate responses. And if no-one complains about bad practice, it won’t stop.

David “Phish of the Day” Harley

ESET Senior Research Fellow

*Phish Phodder: Is User Education Helping Or Hindering? was presented at the Virus Bulletin Conference in 2007 in Vienna, and published in the conference proceedings by Virus Bulletin Limited, the owner of the copyright.