Last month, we presented “The Evolution of Webinject” in Seattle at the 24th Virus Bulletin conference. This blog post will go over its key findings and provide links to the various material that has been released in the last few weeks. Here you can read the paper, conference slides and the recording of presentation.

I have been studying banking trojans for several years now and have looked at many, many different webinjects. After a while, we started to see common patterns in different Webinjects used across different banking Trojans. We saw code and administration panels being reused as well as sellers becoming popular in underground forums. This brought the following question: is there a ubiquitous webinject kit that everyone was using? This paper tries to answer this question.

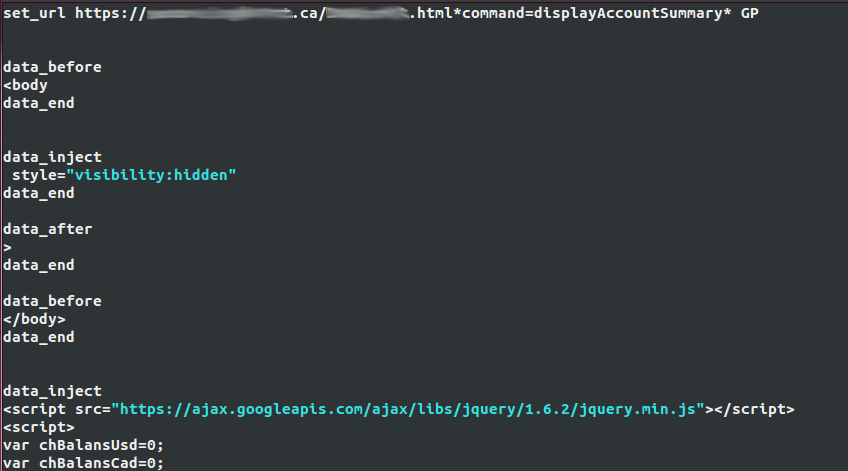

Banking trojans with Man-in-the-Browser (MitB) capabilities are using webinjects to alter the content of a webpage a user sees on a compromised computer. The trojan is able to inject code, such as JavaScript, into the browser to interact with the website content and perform various actions. This technique is quite old, but has evolved considerably in the past few years. Usually, the banking trojans will download some form of webinject configuration file, which contains the target as well as the content that should be injected into the target webpage:

Some webinjects will try to steal personal information from the user by injecting additional fields in a form the user is seeing, thus creating an elaborate phishing page, while others are much more complex and might even try to automate fraudulent transfers from the victim’s bank account to a money mule account. In the case of some banking trojans, the webinject configuration file contains the true attack code, meaning that it is the one that will ultimately bring revenue to the botmaster.

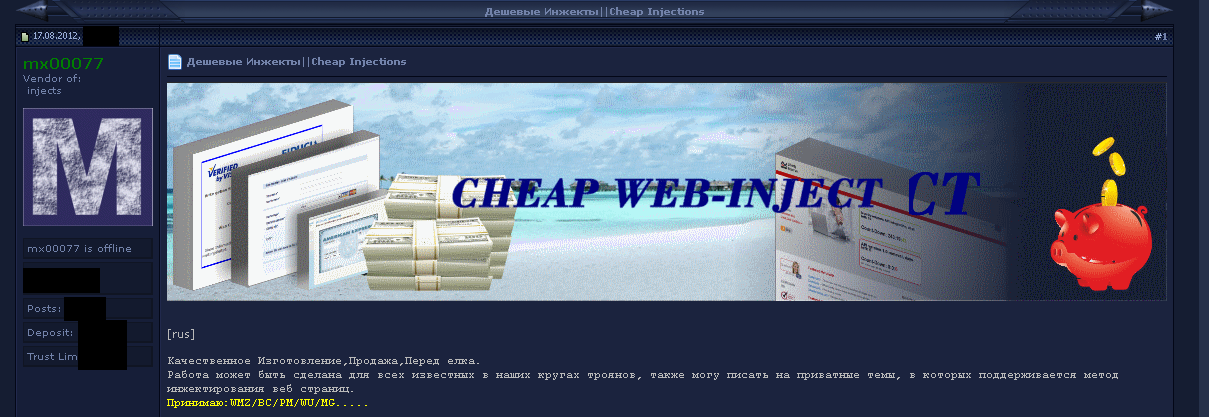

With the number of different banking trojans now available, the increasing complexity of the webinject as well as the need to target different financial institutions around the world, several people have come to specialize in writing webinjects. This has led to the commoditization of the webinjects:

These malicious actors, now selling their creation in underground forums, are a key step in the emergence of a wave of malware using webinjects based on a popular kit. Evidently, without something to sell, there cannot be a dominant player. This offering has evolved quite a bit, too. There are now webinjects on sale targeting a wide array of financial institutions around the world. Some of them are quite complex, bundle Android malware components, have an administration panel and try to evade the two-factor authentication systems implemented by banks attempting to thwart cybercriminal activities. In fact, some webinject coders are bundling as many tools as possible with their webinjects in an attempt to bypass all the security measures that prevent their customers from performing their nefarious activities.

With the commoditization of the webinjects well in place, we can now try to answer our initial question: are there some webinject kits that are more popular than others? The answer is yes. Two of these kits grabbed our attention as they were used by several different banking trojan families. The first one is ATSEngine and the second one is the Injeria platform. Together they have been seen in 7 different malware families and used in numerous different campaigns. Please find additional information on webinject evolution, its commoditization, the emergence of popular kits as well as how to track them in the links to our VB2014 paper provided at the beginning of this post.