A large number of state organizations and private businesses from various industry sectors in Ukraine and Poland have been targeted in recent attacks using malware designed for network discovery and remote code execution, and for collecting data from targets’ hard drives. What makes these attacks interesting – aside from the tense current geopolitical situation in the region – is that they were carried out using new versions of BlackEnergy, a malware family with a rich history, and also the various distribution mechanisms used to get the malware onto the victims’ computers.

The findings of our research will be presented this week at the Virus Bulletin conference in Seattle.

BlackEnergy is a trojan that has undergone significant functional changes since it was first publicly analyzed by Arbor Networks in 2007. Originally conceived as a relatively simple DDoS trojan it has evolved into a sophisticated piece of malware with a modular architecture, making it a suitable tool for sending spam and for online bank fraud, as well as for targeted attacks. BlackEnergy version 2, which featured rootkit techniques, was documented by Dell SecureWorks in 2010. The targeted attacks recently discovered are proof that the trojan is still alive and kicking in 2014.

The latest variants of BlackEnergy are dated September 2014.

BlackEnergy Lite: Less is more?

While the ‘regular’ BlackEnergy trojan is still actively circulating in the wild, we have discovered variants of the malware family, which are easily distinguishable from their older brothers.

We nicknamed the BlackEnergy modifications - first spotted in the beginning of 2014 - as BlackEnergy Lite, due to the absence of a kernel-mode driver component, less support for plug-ins, and an overall ‘lighter’ footprint.

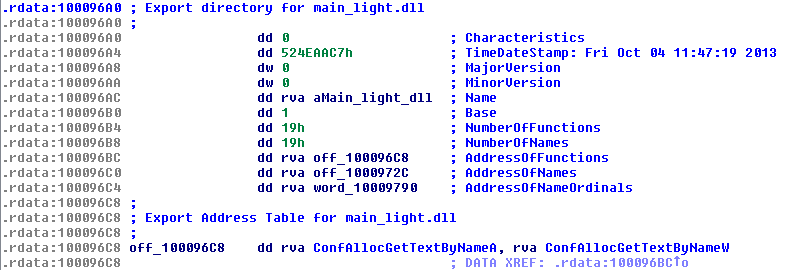

Interestingly, the malware was named similarly by the malware writers themselves, as illustrated by the export directory of an early version of the main DLL:

Note that even the ‘regular’ BlackEnergy samples detected this year have evolved in such a way that the kernel mode driver is only used for injecting the payload into user mode processes and no longer contains rootkit functionality for hiding objects in the system. The light versions go a step further by not using a driver at all. Instead, the main DLL is loaded using a more ‘polite’ and ‘official’ technique – by simply loading it via rundll32.exe. This evolution was previously mentioned in blog posts by F-Secure.

The omission of the kernel mode driver may appear as a step back in terms of malware complexity: however it is a growing trend in the malware landscape nowadays. The threats that were among the highest-ranked malware in terms of technical sophistication (e.g., rootkits and bootkits, such as Rustock, Olmarik/TDL4, Rovnix, and others) a few years back are no longer as common.

There could be several reasons behind this trend, ranging from the technical obstacles that rootkit developers now face, like Windows system driver signing requirements, UEFI Secure Boot – which will be covered by Eugene Rodionov, Aleks Matrosov and David Harley in their VB2014 presentation Bootkits: past, present & future – to the simple fact that it is difficult and expensive to develop such malware. Also, any bugs in the code have a bad habit of blue-screening the system. All the while, possibly even raising suspicion of the presence of malicious code rather than hiding it in the system.

There are several other differences that separate BlackEnergy Lite from the ‘big’ BlackEnergy, in the plugin framework, plugin storage, configuration format, and so forth.

BlackEnergy campaigns in 2014

The BlackEnergy malware family has served many purposes throughout its history, including DDoS attacks, spam distribution, and bank fraud. The malware variants that we have tracked in 2014 – both of BlackEnergy and of BlackEnergy Lite – have been used in targeted attacks. This fact is demonstrated both by the plugins used and the nature and targets of the spreading campaigns.

The purpose of these plugins was mainly for network discovery and remote code execution and for collecting data off the targets’ hard drives.

We have observed over a hundred individual victims of these campaigns during our monitoring of the botnets. Approximately half of these victims are situated in Ukraine and half in Poland, and include a number of state organizations, various businesses, as well as targets which we were unable to identify.

The spreading campaigns that we have observed have used either technical infection methods through exploitation of software vulnerabilities, social engineering through spear-phishing emails and decoy documents, or a combination of both.

In April we discovered a document exploiting the CVE-2014-1761 vulnerability in Microsoft Word. This exploit has also been used in other attacks, including MiniDuke.

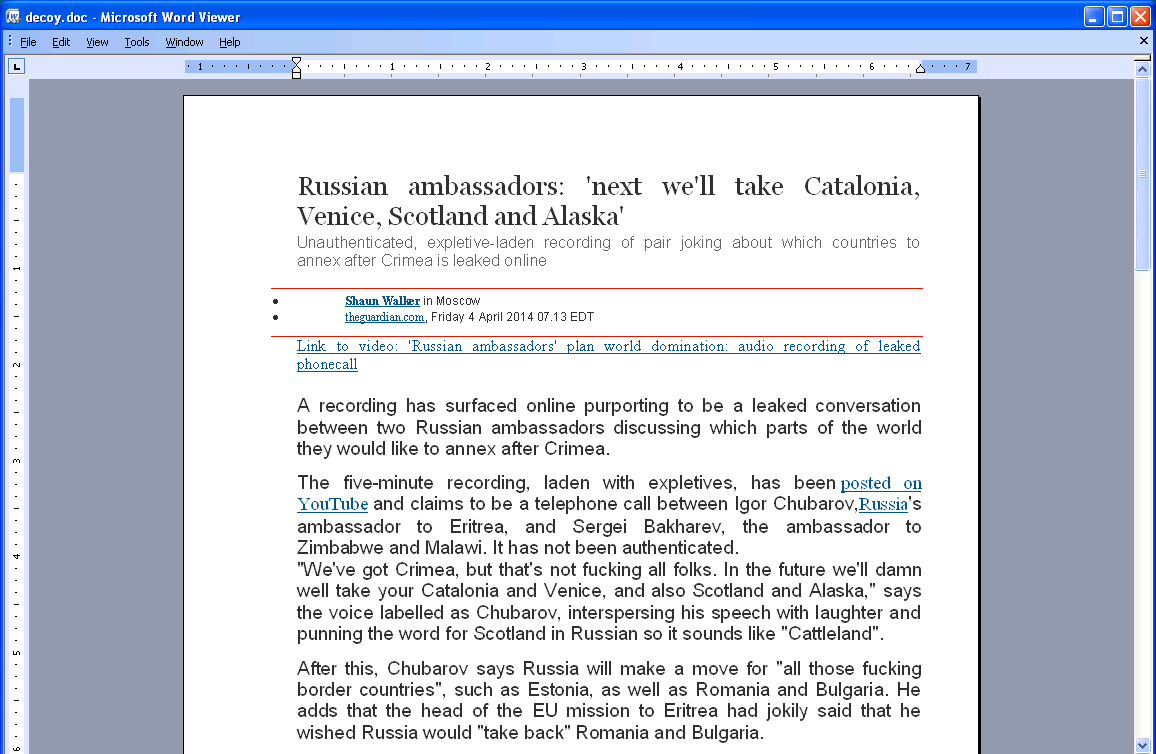

In this case the successful execution of the exploit shellcode resulted in dropping two files to the temporary directory: the malicious payload named “ WinWord.exe” and a decoy document named “Russian ambassadors to conquer world.doc”. These files were then opened using the kernel32.WinExec function. The WinWord.exe payload served to extract and execute the BlackEnergy Lite dropper. The decoy document contained controversial but obviously bogus text as shown below:

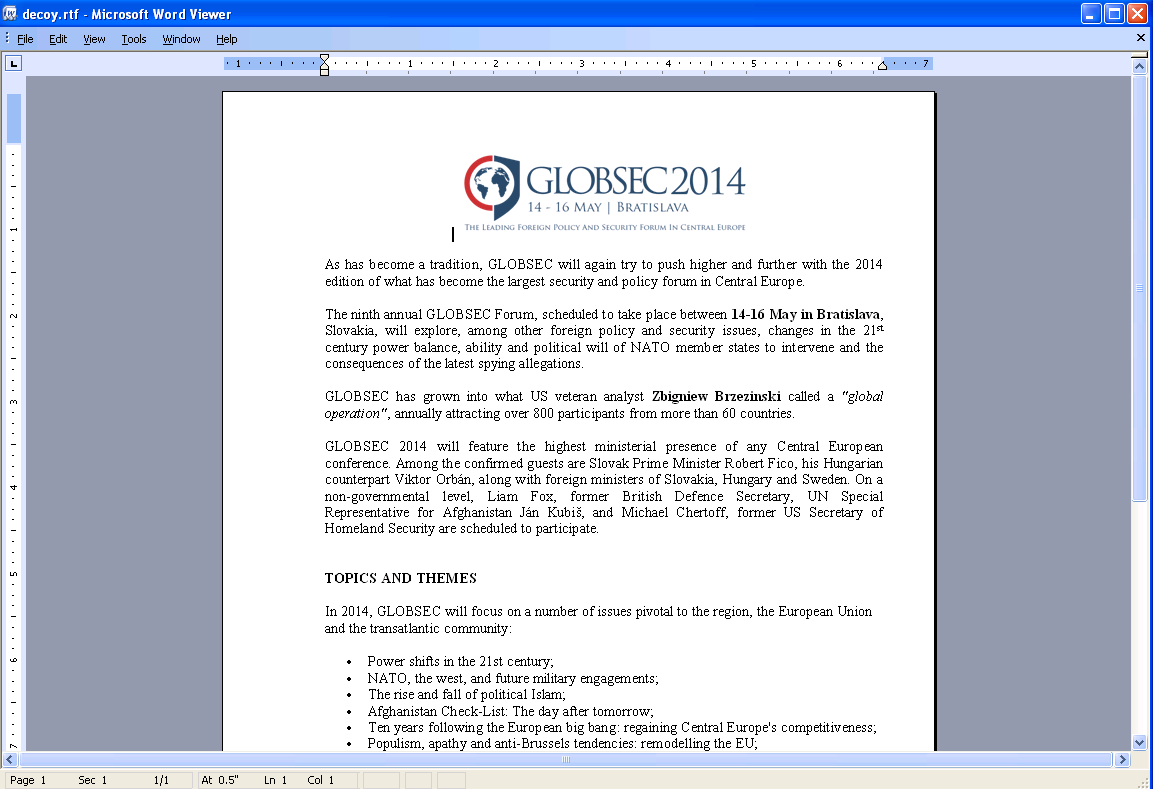

At the same time, another document appeared also exploiting CVE-2014-1761. The text was less controversial than the previous example, but still related to foreign relations. The subject was the GlobSEC forum held in Bratislava this year.

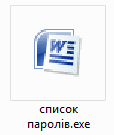

One month later, in May, we spotted another file crafted to install BlackEnergy Lite. This time, however, no exploit was used – the file, named "список паролiв ," which means “password list” in Ukrainian, was simply an executable file with a Microsoft Word icon.

Despite being an executable, this file also contained an embedded decoy document with – you guessed it – a list of passwords. This case was also described by F-Secure in their blog post.

* http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Back_in_Black

| 1 | 123456 |

|---|---|

| 2 | admin |

| 3 | password |

| 4 | test |

| 5 | 123 |

| 6 | 123456789 |

| 7 | 12345678 |

| 8 | 1234 |

| 9 | qwerty |

| 10 | asdf |

| 11 | 111111 |

| 12 | 1234567 |

| 13 | 123123 |

| 14 | windows |

| 15 | 123qwe |

| 16 | 1234567890 |

| 17 | password123 |

| 18 | 123321 |

| 19 | asdf123 |

| 20 | zxcv |

| 21 | zxcv123 |

| 22 | 666666 |

| 23 | 654321 |

| 24 | pass |

| 25 | 1q2w3e4r |

| 26 | 112233 |

| 27 | 1q2w3e |

| 28 | zxcvbnm |

| 29 | abcd1234 |

| 30 | asdasd |

| 31 | 555555 |

| 32 | 999999 |

| 33 | qazwsx |

| 34 | 123654 |

| 35 | q1w2e3 |

| 36 | 123123123 |

| 37 | guest |

| 38 | guest123 |

| 39 | user |

| 40 | user123 |

| 41 | 121212 |

| 42 | qwert |

| 43 | 1qaz2wsx |

| 44 | qwerty123 |

| 45 | 987654321 |

| 46 | pass123 |

| 47 | trewq |

| 49 | trewq321 |

| 49 | trewq1234 |

| 50 | 2014 |

More recent campaigns for spreading BlackEnergy Lite were active in August and even currently in September, according to ESET LiveGrid® threat telemetry system. In one case, specially crafted PowerPoint documents were used, while other attempts to disseminate the malware appear to have been using unidentified Java vulnerabilities, or the remote control software Team Viewer.

More details about these cases will be given on Thursday at the Virus Bulletin conference and published afterwards.