There have been some interesting new developments since we published our report on Operation Windigo. In this blog post you will read about a Linux/Ebury update, more details around our publicly released indicators of compromise (IOC), and we wanted to thank the security community for its help since the release of the report.

Updates to Linux/Ebury

As previously described at length, Linux/Ebury is an OpenSSH backdoor and credential stealer that is the backbone of the operation. It provides the malicious group with all the server resources it needs to run all the other malware services, be it Linux/Cdorked, Perl/Calfbot, or its own infrastructure.

As we were in the process of publishing the report, we stumbled upon version 1.3.5 of Linux/Ebury. We shared the sample, but were unable to provide more details about it in the original report due to time constraints.

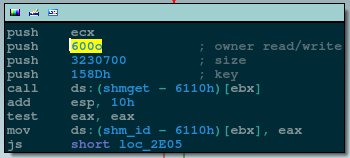

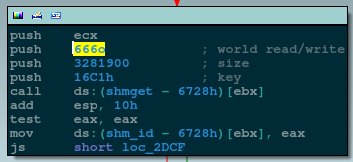

The criminal gang behind Linux/Ebury has updated the code that deals with the shared memory segment so as to restrict its permissions. The permissions were rather broad previously (666) and they have restricted them to only the owner (600). We believe this was done in response to the Ebury FAQ published before our report by CERT‑Bund, which recommended looking out for shared memory with broad permissions (666). This small change could trick the administrators of infected systems into believing that their machines are not infected after all.

| Version 1.3.5 | Older versions |

|---|---|

|

|

Updated Indicators of Compromise (IOC)

Both CERT‑Bund’s FAQ and our own IOCs have been updated to reflect the new permissions. This update doesn’t affect the ssh -G check, but we expect that the malicious group is working on an update right now to defeat this easy check. We will post an update to our blog if that happens.

How to determine if you are infected

Based on the feedback we received, we decided to give more details about the techniques one may use to determine if a machine is infected with the various pieces of malware from this operation.

Here we will focus on several commands and tools useful for system administrators or power-users to investigate individual systems under their control. For larger providers we advise that you look at the network-based indicators that we provided when we released our report.

Linux/Ebury

The backdoored ssh associated with Linux/Ebury carries additional "features" that were added to ssh to accommodate the malicious operators. The -G parameter is one of those. The ssh -G indicator thus relies on the fact that on a clean system there is no -G switch, meaning that when issuing the command one gets the following error:

ssh: illegal option -- GHere is what the console looks like on a clean system:

$ ssh -G

ssh: illegal option -- G

usage: ssh [-1246AaCfgKkMNnqsTtVvXxYy] [-b bind_address] [-c cipher_spec]

[-D [bind_address:]port] [-E log_file] [-e escape_char]

[-F configfile] [-I pkcs11] [-i identity_file]

[-L [bind_address:]port:host:hostport] [-l login_name] [-m mac_spec]

[-O ctl_cmd] [-o option] [-p port]

[-Q cipher | cipher-auth | mac | kex | key]

[-R [bind_address:]port:host:hostport] [-S ctl_path] [-W host:port]

[-w local_tun[:remote_tun]] [user@]hostname [command]

Here is what the console looks like on an infected system:

$ ssh -G

usage: ssh [-1246AaCfgKkMNnqsTtVvXxYy] [-b bind_address] [-c cipher_spec]

[-D [bind_address:]port] [-E log_file] [-e escape_char]

[-F configfile] [-I pkcs11] [-i identity_file]

[-L [bind_address:]port:host:hostport] [-l login_name] [-m mac_spec]

[-O ctl_cmd] [-o option] [-p port]

[-Q cipher | cipher-auth | mac | kex | key]

[-R [bind_address:]port:host:hostport] [-S ctl_path] [-W host:port]

[-w local_tun[:remote_tun]] [user@]hostname [command]

There is no mention of the illegal option. Note that newer versions of OpenSSH will output unknown instead of illegal.

The command that we provided in our previous blog take advantage of this behavior, printing "System clean" if the words "illegal" or "unknown" were matched in the output of ssh -G and printing "System infected" otherwise.

ssh -G 2>&1 | grep -e illegal -e unknown > /dev/null && echo "System clean" || echo "System infected"

One case of a false positive that was brought to our attention was that this technique is ineffective if the Linux distribution used on the system had applied the patches for X.509 certificate support in OpenSSH. Gentoo with the X509 USE flag is one such distribution. Use the shared memory inspection technique described below in that case.

Shared Memory Inspection

Linux/Ebury relies on POSIX shared memory segments (SHMs) for inter-process communications. Currently, it uses large segments of over 3 megabytes of memory.

First, a word of caution: other processes could legitimately create shared memory segments. Be sure to verify that sshd is the process that created the segment, as we show below.

Identifying large shared memory segments can be done by running ipcs -m as root:

# ipcs -m

------ Shared Memory Segments --------

key shmid owner perms bytes nattch

0x00000000 0 root 644 80 2

0x00000000 32769 root 644 16384 2

0x00000000 65538 root 644 280 2

0x000010e0 465272836 root 600 3282312 0

Looking for the process that created the shared memory segment is possible with the ipcs -m -p command:

# ipcs -m -p

------ Shared Memory Creator/Last-op PIDs --------

shmid owner cpid lpid

0 root 4162 4183

32769 root 4162 4183

65538 root 4162 4183

465272836 root 15029 17377

Checking whether the process matches sshd with a ps aux piped in grep with the process id (replacing 15029 with the proper process ID found with ipcs):

# ps aux | grep 15029

root 11531 0.0 0.0 103284 828 pts/0 S+ 16:40 0:00 grep 15029

root 15029 0.0 0.0 66300 1204 ? Ss Jan26 0:00 /usr/sbin/sshd

An sshd process using shared memory segments of around 3 megabytes (3282312 bytes in this case) is a strong indicator of compromise.

Linux/Cdorked

There are a few approaches one can use to detect whether a server is infected with Linux/Cdorked. A simple way is to leverage a specific behavior of the backdoor that redirects any requests to /favicon.iso to Google.

Running this simple curl command:

curl -i http://myserver/favicon.iso | grep "Location:"

will result in the following output on an infected server:

$ curl -i http://myserver/favicon.iso | grep "Location:"

Location: http://google.com/

Depending on configuration, a clean site will return either nothing on this particular command, or a different Location header. Further inspection can be done by removing the grep portion of the command: curl -i http://myserver/favicon.iso.

Additionally, one can look at the shared memory segments similarly to the Linux/Ebury case except that the process creator of the shared memory will be apache (httpd), nginx or lighttpd. On newer variants of Linux/Cdorked remember that the permissions are more strict than before (600 instead of the previous 666).

Be careful when looking for shared memory segments since they could be normal depending on your setup. For example we know that suPHP uses shared memory.

Perl/Calfbot

The presence of a /tmp/... file reveals that a server is infected and the file creation timestamp will accurately reflect the infection time. However, if the server is rebooted or the C&C server sends a KILL command, the file will still be present but the malware will not be running anymore. In order to confirm an active infection, one must test for the presence of a lock on /tmp/... using the following command:

flock --nb /tmp/... echo "System clean" || echo "System infected"

If a system is infected, lsof can be used to see what process owns that lock:

lsof /tmp/...

The following command can also be used to confirm that the targets of the /proc/*/exe symbolic links are the real crond executable:

pgrep -x "crond" | xargs -I '{}' ls -la "/proc/{}/exe"

Anything looking like "/tmp/ " (with a space) in the output is very suspicious.

Note that pgrep requires the procps package. If you can’t install pgrep replace

pgrep -x crond

with

ps -ef | grep crond | grep -v grep | awk '{print $2}'

It’s far from over

After we released our report, we saw the malicious group reaching out to infected systems and reconfiguring them using the Xver command. Unfortunately this prevents us from reliably estimating the number of systems that were cleaned.

Since this command is one of those that triggers our Linux/Ebury snort rule, we would advise ISPs or hosting providers to try to monitor their whole network and protect their customers.

Thank you security community!

Thanks to the widespread interest in our research, we were able to raise awareness of this operation to a point where we have been contacted by many other researchers. We have engaged in new collaborations, received more samples and are getting more and more people notified and systems cleaned. These new collaborations are leading to reinvigorated efforts to shut down this operation -- or at least impede its effectiveness.

We would like to invite anyone who is affected by the operation and would like to help take it down to reach us at windigo@eset.sk.

Linux/Ebury - Version 1.3.5 - libkeyutils.so : e2a204636bda486c43d7929880eba6cb8e9de068