You've probably seen the headlines: Thousands of Linux servers used in cyber attacks on U.S. banks; Tens of thousand of Apache servers now distributing malware; Massive served-based DDoS attacks are threatening the Internet! There's certainly a lot of talk about malware in the web server space (the report about "Apache backdoor being used to serve Blackhole exploit kit" published here on We Live Security has attracted more readers in seven days than any previous article).

But are these events relevant to the security of your company's systems? That's a fair question to ask because a lot of people and companies that use Linux don't actually think of themselves or their company as being Linux users. As it turns out, the compromise of Linux computers running Apache (or Lighttpd or nginx) web servers could cause you and/or your company a lot of damage, ranging from data breaches to losing your website, even if you don't think of yourself as a Linux user.

Linux web servers by the millions

In fact, I'm willing to bet your company does use Linux in some form or other, most likely on your website. (Linux could also be part of your family's digital profile as well, given that the Android smartphone and tablet operating system is built on Linux, as are devices from DVRs to DVD players, routers and wireless access points.)

If you have a website hosted on a Linux server, now is the time to review its security.Where is your website hosted? With a hosting provider? On a shared server in a data center? Handled by the company who designed it for you? If you're not sure, now is the time to find out. And while you're at it, check if it is running on a Linux box.

As for Apache, some 350 million web servers run Apache. Of the 1 million busiest websites, 60% are running on Apache (Netcraft Web Server Survey, February, 2013). And it's safe to say that most of these Apache web servers are running Apache on some form of Linux.

When it comes to cyber security, Linux and Apache have a history of being relatively secure in design and relatively easy to deploy securely, if you know what you're doing. When web sites running on Linux/Apache have been hacked in the past, it was usually via PHP and SQL, not holes in Linux/Apache code. Today, attacks on these machines exploit a range of vectors, including malicious Apache modules, weak authentication, and holes in commonly used applications such as cPanel, Plesk, Joomla, Drupal, and WordPress, in addition to good old PHP and SQL.

BTW, if you don't think your company is using PHP and SQL, you might want to think again. For a start, all WordPress-based websites use PHP/SQL and there are over 60 million of those. The acronym LAMP is sometimes used to refer to this open source software ecosystem: Linux, Apache, MySQL, PHP. While you can create a fairly secure web server with LAMP, there are plenty of insecure ones out there, as we will see.

Why bad guys want your LAMP machine

Before we take a look at some of the specific security challenges that have surfaced recently on Linux systems, it is worth considering why such systems appeal to the bad guys. In the "good" old days, web server hacking was typically done in order to deface websites, causing embarrassment to the website owner (as in the 1996 and 2011 defacements of the CIA website).

These days much of the value of a hacked web server comes from several advantages it offers as an attack platform relative to desktop and laptop computers. Of course, if there is any personal or proprietary data on the server that can be sold or otherwise used for gain, that makes for a good penetration motive as well, but the server alone offers these attack platform benefits:

- Reliable and always on: By their very nature, web servers are always on, more so than your typical home or office laptop or desktop. Web servers are typically located in secure facilities with backup power. They are generally immune to power outages but also configured to restart in the event of a power cut, or any other "event" for that matter. This makes them ideal for criminal activity which needs 7x24 access to processing power, storage, and bandwidth. Such activity includes executing Distributed Denial of Service attacks and distributing malicious code used for financial fraud, spamming, DDoS, spying, identity theft, illegal pharmaceutical sales, and more.

- Largely unattended: Have you or your company ever started a web project and then abandoned it or put it on the back burner? I'm betting that millions of people have, creating a large pool of under-administered web servers out there, ripe for takeover from owners who are not paying attention. That lack of attention translates into lower detection rates and longer service times per compromise.

- Plenty of bandwidth: Most web servers are sitting on high speed Internet connections designed to handle large amounts of traffic. This adds to their appeal to the bad guys who may want to tap that bandwidth for nefarious activities.

The impact on your business

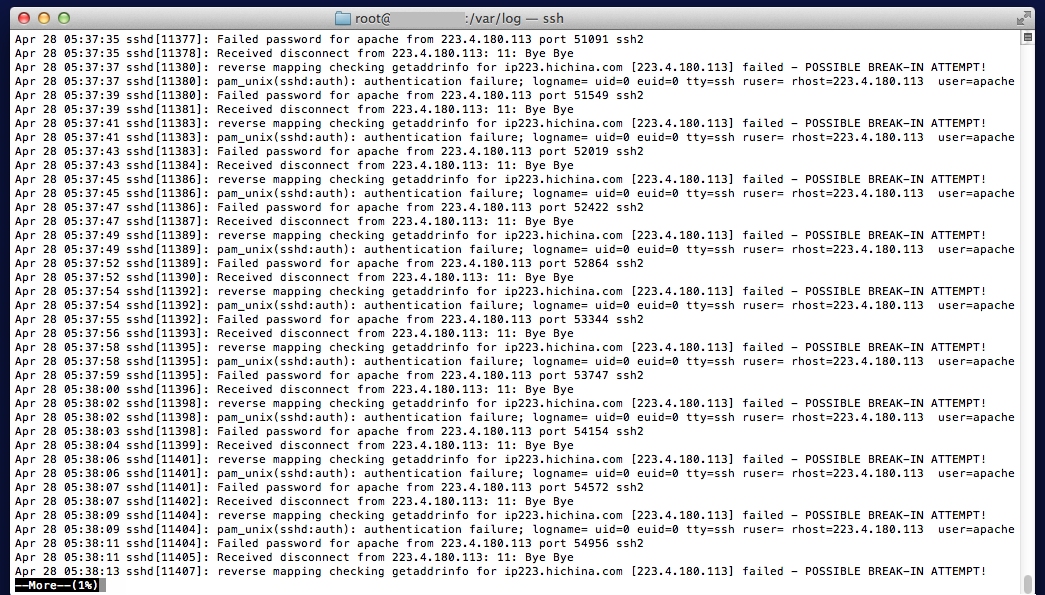

If you're still having trouble believing your web server is now a target for bad guys, take a look at this log file from a typical server of the kind used to host websites for small businesses and non-profits. You don't have to be a Linux expert to see that someone is trying to access the box with the wrong passsword every two seconds, at five thirty in the morning:

The attacker, or rather the attacker's script, is trying to get into the box via non-standard ports (51091, 51549, etc.). These are sometimes used by system administrators to obscure SSH access, for which the standard port number is 22.

Bear in mind that this log is not from a major shopping website or big corporation, this box is a virtual private server hosting small business websites (it is the kind of box you would have if you set up a website through hosting providers such as GoDaddy, HostGator, or 1&1 Internet). The attacker probably has no knowledge of what data is on this particular server but is simply trying to gain access to use the processing, storage and bandwidth of the box for illegal purposes.

Even if they don't succeed, attacks like this can slow your website down, which is generally a bad thing, particularly if you are conducting business on your website. If the attack succeeds and the bad guys start using your web server for illegal purposes, that could well result in your website being blocked by web browsers, or turned off. Clearly that is not good for business and is potentially costly to fix, even if you have a reliable backup, diagnose, remediate, and restore process in place. Otherwise expect to expend a fair number of un-budgeted resources on getting back to square one. (You can't count on simply restoring the server from the last backup unless you know that it is free of malicious code, such as back-doored Apache modules.)

Sadly, if you were not paying attention to this server, a notice from the Abuse department at the hosting provider may have been the first you heard of the hack. Or you might get calls from customers saying that they can't get to your site because their web browser or anti-malware application has flagged your site as malicious. All of these are pretty much nightmare scenarios for any business or organization that depends on its website.

Trouble in LAMPland

Here's a quick run down of some of the current high profile cyber-badness that involves Linux Apache machines. (Note that I'm not blaming Linux or Apache for these problems, they simply simply represent a particular operating environment currently under attack).

Bank DDos Attacks: The escalating rounds of DDoS attacks on banking websites in America that started last September are powered for the most part by compromised Linux Apache servers marshaled into a botnet initially called Brobot. Additional botnet segments with different names have since been created by the attackers. The whole operation is sometimes referred to as Operation Ababil, described in plenty of detail in this excellent presentation by Andre Correa of PhishLabs. Compromise of servers recruited into the Ababil botnets is often via Joomla or WordPress, via unpatched vulnerabilities or brute force (repeated login attempts using a list of common passwords). So far, Ababil is a classic case of hacking into web servers for their processing capacity and bandwidth, not the data that is stored on them.

Darkleech Chapro: In December of last year, ESET researchers published a detailed analysis of a piece of Linux Apache malware they dubbed Chapro, also known by the more evocative name of Darkleech, the recent spread of which has been documented Dan Goodin at Ars Technica and others. The infection of 20,000 servers in two weeks made headlines and served to remind people in charge of Apache servers that taking all the appropriate steps to secure them was now more important than ever. (We should make it clear that this malware does not exploit a vulnerability in Apache but installs as a module under Apache, in other words Apache servers are being used to serve up bad code, not a corrupted version of Apache.)

WordPress Brute Force Botnet: As reported a few weeks ago by Brian Krebs and described by Dean Valant of Houston-based HostGator, one of the largest hosting providers in the U.S., someone is building a botnet of infected WordPress installations using brute force attacks. According to Valant:

"As I type these words, there is an on-going and highly-distributed, global attack on WordPress installations across virtually every web host in existence. This attack is well organized and again very, very distributed; we have seen over 90,000 IP addresses involved in this attack."

The long-term goal of this large-scale criminal hacking is not yet known, but it underlines the degree to which web servers are now targeted as potential attack platforms.

Linux/Cdorked: ESET researchers recently published technical analysis of a piece of Apache malware dubbed Linux/Cdorked.A, a sophisticated and stealthy backdoor meant to drive traffic to malicious websites. The risk to organizations using Apache or Lighttpd or nginx web servers for their web server is this: blocking of their website because of its recruitment into a malware distribution system. Note that in this context, the backdoor means that a part of the web server code, in this case httpd, has been altered to behave badly. System defenses like Tripwire should catch this, but it is suspected that a significant percentage of website hosting servers do not use such controls. We certainly urge system administrators and hosting providers to check their servers and verify that they are not affected by this threat (detailed instructions and a free tool to perform this check were provided).

System administrator vulnerability: The temptation to mess with the systems in your care can be to much for some people. Last month we heard of a former HostGator employee being arrested and charged with rooting 2,700 servers, installing a back door that could enable all manner of malicious activity. While there is no known connection to organized cyber crime in this case, the fact that criminals are known to pay for compromised accounts makes it clear that those with direct access to systems are a potential point of failure. (Bear in mind that those 2,700 servers could be hosting more than 30,000 websites.)

Roadmap to Linux Apache security

To avoid becoming a victim of this new wave of system abuse, consider following this roadmap:

A. Assess: Are you or your business using any Internet-connected Linux Apache web servers? Where are they located? Who manages them? What is their function? How valuable are they to your organization? What security measures are in place to protect them? Who can help you secure them?

B. Build your policy: Commit to protecting your Linux Apache server[s] as a matter of policy, and define policies for security and maintenance, assigning responsibility for these functions to a specific person or role within the organization.

C. Choose your controls: Decide what security measures are appropriate. For example, should access to services on the box be restricted to certain IP addresses? Is two-factor authentication needed to defeat brute force password attacks? Do you need anti-malware scanning installed on your server[s].

D. Deploy controls: Have qualified persons put controls such as two-factor authentication in place and test that they work. Many of the technical security steps can be found in online document and forms although deployment may require hiring specialists. (Here's a good guide to hardening Apache, and one for securing Linux web servers.)

E. Educate employees, service providers: Make sure everyone involved in management of the web server and its content is aware of the controls and of their responsibility to protect the systems.

F. Further assess, audit, test: Review your progress on A through E against the latest news on the scale and sophistication of attacks to ensure that your response matches the threat.

(Note that this ABCDEF approach closely mirrors the cyber security roadmap that I will be writing about in more detail in future blog posts.)

If your firm has experienced hacking of a Linux Apache server, we would like to hear from you, via a comment or email to askeset [at] eset [dot] com.