Had we looked at a map of malware detections in Brazil a year ago, we would have seen that the two main computer threats were the downloaders that installed banking trojans, and the banking trojans themselves. Today the situation remains the same, but with an extra special ingredient: while threats used to be Windows .exe files, today there are also Java .jar files, as well as Visual Basic Script and JavaScript among the top 10 threats.

To understand this change in the platforms used by cybercriminals, we will, in this article, analyze both a JavaScript and a Java threat.

But first, let's take a look at the top 10 threat detections in Brazil for the first five months of 2016. The most prevalent one is a generic detection of obfuscated scripts. Even though the final payload may vary, below we will see a connection between this kind of detection and banking trojans. Although we will not elaborate on the other nine threats in this article, it is worth noting the many different programming languages and platforms that are being used in attacks that target Brazil today.

| Name of the Threat | Level of Prevalence |

|---|---|

| VBS/Obfuscated.G | 10.52% |

| JS/Danger.ScriptAttachment | 4.60% |

| VBS/Kryptik.FN | 3.50% |

| Win32/Toptools.A | 3.09% |

| JS/TrojanDownloader.Iframe.NKE | 2.66% |

| Java/TrojanDownloader.Banload.AK | 2.24% |

| Java/TrojanDownloader.Banload.AE | 2.18% |

| Win32/Toptools.D | 2.18% |

| JS/Adware.Agent.L | 2.09% |

| JS/Toolbar.Crossrider.G | 2.06% |

In particular, at ESET’s Latin American Malware Research Laboratory we have seen a malware campaign in which the threats are being hosted on the MEO cloud service, which is based in Portugal. In most cases, these are banking trojans. The propagation method is carried out through emails with a link to download the malware.

We can take one of those files as an example: Boleto_NFe_1405201421.PDF.js, detected by ESET as VBS/Obfuscated.G.

Although the script code is obfuscated, the encryption used is easy to reverse. Even without decrypting, we can see that a file disguised as a .jpg file is downloaded to the ProgramData folder under the name flashplayer.exe, which is then executed.

![[01] scriptjsofus](https://web-assets.esetstatic.com/wls/2016/07/01-scriptjsofus.jpg)

This file – flashplayer.exe – is, in turn, a banking trojan downloader, which downloads and runs a third executable named Edge.exe. This executable is detected as a Win32/Spy.KeyLogger.NDW variant; however, apart from recording the keystroke events, it has all the functionalities of a banker. Among its many features, it obtains the address of the website the user is visiting and checks it against a list of banking websites, using DDE, as we described in the article Cómo reconstruir lo que envía un troyano desde un sistema infectado (How to rebuild what a trojan sends from an infected system).

The difference is that, this time, the trojan includes code for a larger number of browsers including:

![[02] codigonavegadores](https://web-assets.esetstatic.com/wls/2016/07/02-codigonavegadores.jpg)

The strings are encrypted with a custom XOR-based algorithm. some of them can be seen below. It is clearly trying to steal access credentials to Brazilian banking sites.

We can see how cybercrime is evolving in Brazil, migrating to new platforms and using various programming languages in its attempt to evade detection. Its goals, however, have not changed that much – stealing banking credentials is still the most profitable form of attack and is, therefore, the most common one.

Now, while examining the cloud services used to host the JavaScript malware, we found that they were also hosting other computer threats found in Brazil's Top 10. In particular, we have found a lot of activity related to malicious files that are detected by ESET as Java/TrojanDownloader.Banload.AK.

These files are .jar executables, with names such as Boleto_Cobranca, Pedido_Atualizacao, or Imprimir_Debitos. Once decompiled, we get obfuscated code with extremely long variable names and methods:

![[03] codigoofuscado](https://web-assets.esetstatic.com/wls/2016/07/03-codigoofuscado.jpg)

Despite this obfuscation, we can see some of the imports in the image. The last five imported classes have to do with encryption, since they use the DES symmetric algorithm. Thus, if we are able to identify the decryption methods, and replace the names of those methods and variables with more representative ones, we will have something like this (comments have also been added):

![[04] descifradoDES](https://web-assets.esetstatic.com/wls/2016/07/04-descifradoDES.jpg)

The key used for decryption is the Java class name. Therefore, if we adapt the code in main, we can make the malware decrypt all its strings for us. In fact, we can parse the main class to search for these strings, and then pass this list to our modified code to carry out the decryption process.

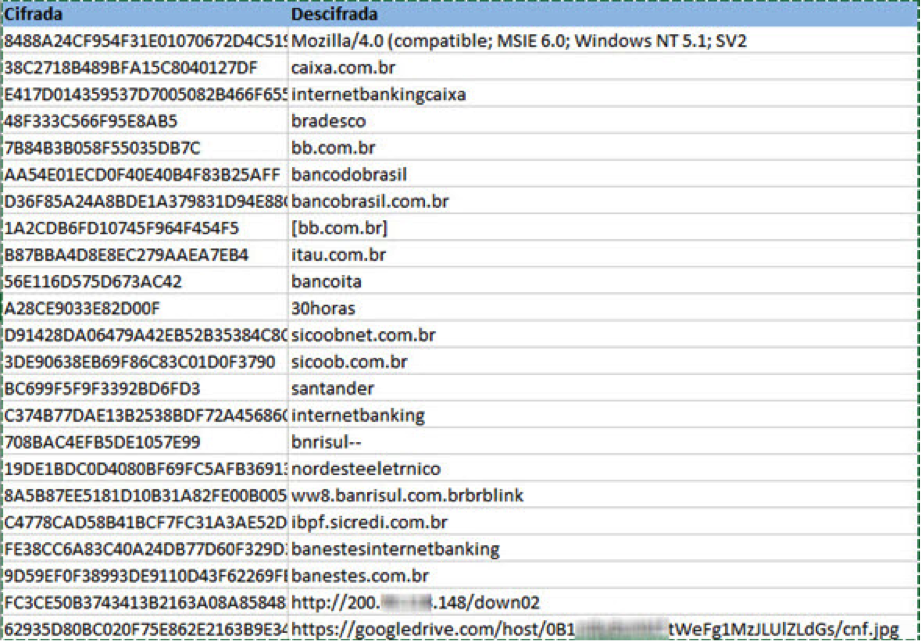

Finally, we will see some encrypted and decrypted strings:

![[05] stringsDescifradasJava](https://web-assets.esetstatic.com/wls/2016/07/05-stringsDescifradasJava.jpg)

We have underlined the server's IP address contacted by the malware. Note that the C&C server varies in the different samples we have analyzed. A Visual Basic Script file is then created, executed by cscript.exe.

It is worth noting that the analyzed files also have more features, which can be found in the other imports. One of the most interesting features of the malware is its ability to detect virtualized environments, after which it would self-terminate. Some other functions download files from the internet, as can also be seen in the rest of the imports:

![[06] importsjava](https://web-assets.esetstatic.com/wls/2016/07/06-importsjava.jpg)

Although the diversity of languages and platforms used in the malware attacks in Brazil is remarkable, the objectives of cybercriminals and their propagation methods remain the same.

The two downloaders analyzed so far were being hosted by a Portugal-based cloud service. We found, however, a third downloader, hosted on a different file-sharing service. The latter is a Visual Basic script, which shows us the diversity of languages and platforms used in malware attacks in Brazil.

All these threats use the same propagation method – fraudulent emails purporting to be from banks. Once we download the .vbs file, we can see that it is obfuscated:

![[07] vbs_ofuscado](https://web-assets.esetstatic.com/wls/2016/07/07-vbs_ofuscado.jpg)

The hex-encoded, XOR-obfuscated main routine of this script can easily be restored to its original code in Visual Basic Script. That code downloads a password-protected archive that is then extracted with another application, also downloaded by the malware: 7za.exe. While not in itself malicious, it is used to obtain an executable from the downloaded .zip file, which is then run by the script:

![[08] vbs_desofuscado](https://web-assets.esetstatic.com/wls/2016/07/08-vbs_desofuscado.jpg)

The Portuguese comment “link do seu do modulo“ in the excerpt of the original code, above, can be translated as "link to your module". Then the word your caught our attention, making us think that the script was created with a script generator, or that the code was copied from some example code from elsewhere, since it does not say my module.

Regarding the file that was extracted and executed by the script, ESET detects it as a variant of Win32/Packed.Autoit.R, introducing yet another programming language. The executable, generated from an AutoIt script, has no purpose other than to inject a banking trojan into memory. First, a process is created in a suspended state; then its image is replaced in memory by the malware; and finally, its execution is resumed (this technique is known as RunPE).

The injected executable is detected by ESET as Win32/Spy.Banker.ACSJ, a banking trojan written in Delphi (which we typically see in Brazil). It has encrypted strings that use the same custom algorithm for decryption as the banker we mentioned earlier (the one installed by the JavaScript downloader).

Although we will not discuss the details of this banking trojan in this article, it is worth mentioning that it does not use DDE, as did the banker installed by the JavaScript threat. Instead, it imports functions from oleaut32.dll, so as to automate malicious tasks whenever it detects that the victim is browsing certain banking websites using Internet Explorer. When the victim browses a targeted site, this banking trojan loads fake forms with images that are very similar to the ones used in legitimate sites, with the purpose of harvesting banking credentials and account information.

![[09] bancos](https://web-assets.esetstatic.com/wls/2016/07/09-bancos.png)

We have been able to associate threats in multiple programming languages or platforms with the same campaign. It is amazing how many different techniques and resources cybercriminals are using to propagate their threats in Brazil. And even though the final stage in these attacks is still a banking trojan written in Delphi - the most common malware attack scenario seen in recent years in Brazil - we have now started to see that its code is being updated to keep up with the new security measures implemented by Brazilian banks.

Analyzed Samples

| SHA-1 | File Name | Detection Name |

|---|---|---|

| 8ceaae91d20c9d1aa1fbd579fcfda6ecfdef8070 | Boleto_NFe_1405201421.PDF.js | VBS/Obfuscated.G |

| 016bd00717c69f85f003cbffb4ebc240189893ad | flashplayer.exe | Win32/TrojanDownloader.Banload.XGT |

| c4c4f2a12ed69b95520e5d824854d12c8c4f80ab | Edge.exe | Win32/Spy.KeyLogger.NDW variant |

| 2c8385fbe7c4a57345bf72205a7c963f9f781900 | Imprimir_Debitos9874414541555.jar | Java/TrojanDownloader.Banload.AK |

| 363f04edd57087f9916bdbf502a2e8f1874f292c | Atualizacao_de_Boleto_Vencido_10155455096293504.jar | Java/TrojanDownloader.Banload.AK |

| 8b50c2b5bb4fad5a0049610efc980296af43ddcd | LU 1.jar | Java/TrojanDownloader.Banload.AK |

| d588a69a231aeb695bbc8ebc4285ca0490963685 | Comprovante Deposito-Acordo N7656576l (3) (4) (4).vbs | VBS/TrojanDownloader.Agent.OGG |

| dde2af50498d30844f151b76cb6e39fc936534a7 | 7b0gct262q.exe | Win32/Packed.Autoit.R |

| 256ad491d9d011c7d51105da77bf57e55c47f977 | Win32/Spy.Banker.ACSJ |