[Updated 2/22/16 to reflect additional perspective on patient withholding.]

As 2015 slides into the cybersecurity history books as “the year of the healthcare breach” I decided to examine one aspect of medical data privacy that is sometimes overlooked: the impact of breaches on patient-doctor information exchange. Specifically, I’m concerned that high profile healthcare-related IT security breaches may lead more people to withhold sensitive information from their doctor because of fears that it will be exposed due to weak privacy protection or weak security controls.

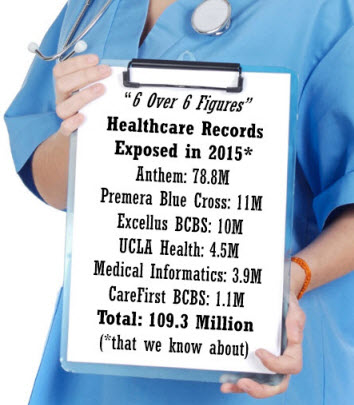

That such fears exist is all too evident when you talk to people about the huge healthcare data breaches of 2015, the six largest of which compromised more than 100 million records. I have spoken to people whose data was exposed in those attacks and who subsequently experienced one or more forms of attempted identity theft.

That such fears exist is all too evident when you talk to people about the huge healthcare data breaches of 2015, the six largest of which compromised more than 100 million records. I have spoken to people whose data was exposed in those attacks and who subsequently experienced one or more forms of attempted identity theft.

Of course, it is hard to tie a specific breach of your data to a specific instance of identity theft. But if the theft comes soon after a breach at Company A, who has your information, you may well suspect the Company A breach is the source of your problem. When a whole string of breaches occur in a short period of time, your company may get blamed even if you are sure that your breach did not result in ID theft.

The Withholding Problem

The need for doctors to keep patient information confidential is as old as the practice of medicine itself. (In the original version of Hippocratic Oath a doctor would vow to hold patient information “sacred and secret within my own breast”.) Simply put, doctors cannot provide safe and effective care to patients if those patients don’t share with them all of the relevant information. Of course, there are numerous reasons why a person might choose not to tell their doctor everything. Some reasons predate computers and are as old as society itself, including shame, embarrassment, and fear of censure.

However, fears about unauthorized access to, and abuse of, electronically stored personal health information were voiced as soon as database technologies began to emerge in the latter half of the last century. In fact, the US government agency that was then known as the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) prompted some of the first serious thinking about the impact of computer databases on society. A 1973 document commissioned by that agency and subsequently known as the HEW Report, examined the many fears raised by the growing computerization of personal information.

More withholding? Survey says...

While government agencies and companies have worked for decades to reassure people that their data privacy is protected, it seems reasonable to expect that the recent rise in security breaches in the healthcare sector will have fueled fears about the confidentiality of medical records, far more of which are computerized now than in the past. To assess the scale of the problem, last month I put the following question to 750 American adults age 18 and older:

“Have you withheld information from your healthcare provider due to concerns about the security or privacy of your medical records?”

More than one in eight said yes, they had withheld information from their healthcare provider due to concerns about the security or privacy of their medical records (13.2%). Conversely, 86.8% said they had not withheld (with a margin of error of +/-3%). The 13% figure is potentially quite significant because some previous studies reported a much lower number. For example, from 2012 through 2014 the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) surveyed patients about withholding of information from health care providers due to privacy or security concerns and got much lower numbers: 7%, 8%, and 5% respectively (see report - PDF). If further research bears out the higher number from my survey, it could be argued that the large medical data breaches of 2015 have doubled patient concerns. (See added notes below on the relative level of patient withholding due to privacy and security concerns.)

Not surprisingly, the results from my survey vary somewhat according to demographics. The folks most likely to withhold appear to be those living in the West (18.5%) and those who are in late middle age (nationally, 15.9% of folks age 55-64 withheld). The least likely to withhold are people in the Midwest (7.6%) and folks age 65 and older (6.7%). Interestingly, rural and suburb dwellers were less likely to withhold than urbanites (16.7%). In terms of income level (annual, inferred) there was a band of trust from $25K up to $74K, but those with incomes outside those numbers withheld at a higher rate than the mean. Interestingly, when I ran the same survey in Canada, I found that Canadians were less likely to withhold than their US counterparts (10% v. 13.2%).

Given the potential for patient withholding to undermine diagnosis and treatment, not to mention medical research, I think many folks will find these numbers worrying. For health IT managers, these numbers suggest that better information security could lead to better health outcomes by reassuring people that their medical secrets are safe from prying eyes. Conversely, what we are seeing could be an additional and potentially serious downside to poor medical data security, in addition to the many others (which range from reputational damage to life threatening medical errors and medical identity theft).

Past Privacy Findings

For those who want to dig a little deeper and get some historical context on the withholding issue, check out the study of medical privacy carried out in 1999 by the non-profit California Healthcare Foundation (CHF). When CHF investigated medical privacy it asked: “In recent years, do you think it has become more difficult or less difficult for people in this country to keep personal information private and confidential, or is it about as difficult as it was in the past?” Almost 80% said it was more difficult. Furthermore, more than half of all US adults said the shift from paper record keeping systems to electronic or computer-based systems “made it more difficult to keep personal medical information private and confidential.”

Then CHF asked a question akin to the one I posed recently: have you ever done “something out of the ordinary to keep personal medical information confidential?” Fifteen percent of adults nationally (and 18% in California) said they had done so. Steps taken to protect medical privacy that were reported in the 1999 study included numerous behaviors that could have put people's health at risk. These included: “going to another doctor; paying out-of-pocket when insured to avoid disclosure; not seeking care to avoid disclosure to an employer; giving inaccurate or incomplete information on medical history; and, asking a doctor to not write down the health problem or record a less serious or embarrassing condition.”

In 2005 the study was revisited and it was found that consumers remained concerned about the privacy of their personal health information, with around two thirds saying they were “somewhat” or “very concerned” about the privacy of their personal medical records. The concern was even greater among racial and ethnic minority respondents. One out of eight consumers reported putting their health at risk by engaging in such behaviors as: “avoiding their regular doctor, asking their doctor to fudge a diagnosis, paying for a test because they didn’t want to submit a claim, or avoiding a test altogether.” These risky behaviors were more likely among the chronically ill, younger people, and racial and ethnic minorities. In a more recent study, half of all consumers admitted to lying or deliberately misleading a physician during an office visit.

Clearly, this is a topic worthy of further research. I am now looking for studies that attempt to quantify the medical importance of the information withheld by patients. If withholding was found to be of critical importance for just half of the people doing it, that would still amount to a significant impediment to effective healthcare, one that is arguably attributable to shortcomings in our efforts to ensure the privacy and security of patient information. Among the many reasons for doing a better job of medical data protection, this has to be near the top.

Notes on Methodology and Other Studies

My survey was conducted using Google Consumer Surveys, a service that has been found to relatively accurate (see http://www.people-press.org/2012/11/07/a-comparison-of-results-from-surveys-by-the-pew-research-center-and-google-consumer-surveys/ and this paper https://www.google.com/insights/consumersurveys/static/consumer_surveys_whitepaper_v2.pdf).

Added 2/22/16: Thanks to a very helpful tip from @SuzanneWidup I checked out two papers that explored patient withholding due to privacy and security concerns and were referenced in the Verizon PHI Data Breach Report (which I read shortly after it came out in December, so my bad for not spotting those earlier). These papers analyzed data from Health Information National Trends Survey. This is a cross-sectional, nationally representative survey of American adults sponsored by the National Cancer Institute which serves as a national-level surveillance vehicle for both cancer and health communication. In other words, it contains data about whether or not patients withhold information from doctors. In their article "The double-edged sword of electronic health records: implications for patient disclosure" authors Celeste Campos-Castillo and Denise Anthony report that "13% of respondents reported having ever withheld information from a provider because of privacy/security concerns." Furthermore, while "bivariate analysis showed that withholding information was unrelated to whether respondents’ providers used an EHR," further multivariable analysis: "revealed a positive relationship between having a provider who uses an EHR and withholding information."

From the perspective of that article, based on data gathered in 2012 and 2013, my finding of 13% is not an increase in withholding. However, it is an increase relative to the findings of the ONC, which from 2012 to 2014 conducted "a nationwide survey of consumers to examine privacy and security concerns and preferences regarding electronic health records (EHR) and health information exchange (HIE)." However, in a data brief refreshed just this month that summarizes trends from 2012 to 2014 related to individuals' privacy and security concerns and preferences, the ONC found that in 2015: "5% of individuals nationwide withheld information from their healthcare provider due to privacy or security concerns."

Other findings in that ONC briefing suggested a decline in concern about EHR privacy and security from 2012 to 2014, but the authors also made this very sensible observation: "it is important to note that these perceptions reflect individuals' points of view prior to announcement in 2015 of several large health care information breaches. Whether these recent breaches may negatively impact individuals' perceptions related to the privacy and security of their medical records and exchange of their health information is unclear and warrants monitoring." I look forward to seeing more results as the year progresses.