Without a doubt, malware is – and has always been – one of the main threats to IT. Over the years, it has become one of the primary causes of security incidents, from the early years with viruses, to more sophisticated and relatively high-impact threats such as ransomware.

Similarly, the reasons for developing and distributing malicious code have changed over time from testing a system’s functionality in order to gain recognition for the malware’s creators, to reaping some kind of benefit – mainly financial profit – in an increasingly quicker timeframe.

In this post, we will take a look at the evolution of ransomware, the type of malware used mostly for hijacking user data, from its initial versions to the most recent cases, where it is now sold on the market as a service.

The beginnings of information hijacking, way back in 1989

Much has been written about cases of ransomware in these pages, and particularly about the many different campaigns to distribute and infect machines with variants of this family of malware, which has proved highly profitable for its developers. For example, in the 2015 Trustwave Global Security Report, it was estimated that cybercriminals can get up to 1,425 per cent return on investment for a malware campaign of this kind.

Although it is not a new idea, information hijacking has acquired new relevance in recent years due to its impact on users and companies that have been negatively affected by malware which performs this function, and also due to its increasing diversification.

The first case of ransomware dates back to 1989, with the appearance of a trojan called PC Cyborg. This replaced the AUTOEXEC.BAT file, hid the folders and encrypted the names of all the files on the C drive, rendering the system unusable. The user was then asked to “renew their license” by paying $189 to the PC Cyborg Corporation.

In the years that followed, new versions of programs seeking to extort money from users were identified, but unlike the symmetric encryption used by PC Cyborg, these newer programs employed asymmetric encryption algorithms with increasingly long keys. For example, in 2005, the GPCoder came to light, followed by a series of variants, which first encrypted files with certain extensions and then demanded a payment of between $100 to $200 as a ransom for the encrypted information.

Some variants derived from ransomware

After the first cases of ransomware, other types of malware emerged that worked on the same principle of making information inaccessible. However, rather than using encryption, they instead blocked the user’s system.

One of these is WinLock, a malware program that was first identified in 2010. This would infect the user’s computer, then block it and display a message across the screen that demanded a payment. To obtain the unblock code, the affected user would have to send an SMS message which would cost them around $10. So, rather than affecting files, the focus had turned to blocking access to the user’s equipment and information.

In a similar vein, 2012 saw the emergence of the so-called “police virus” Reveton, which blocked access to the affected user’s system. This malware would display a fake message – supposedly from the local police authority of the country where the threat was taking place – telling the user that they had broken the law. To restore access to their system, a “fine” would have to be paid.

Or so the user thought – regaining access was actually relatively simple. By starting the system in safe mode and then deleting a registry key, the user could access their equipment again without needing to pay the money demanded.

When did ransomware increase in quantity and complexity?

In recent years there have been new waves of malware designed to encrypt the user’s information, enabling cybercriminals to demand a ransom payment that will allow the user to decrypt the files, and these are detected by ESET security solutions as filecoders.

In 2013, we learned about the importance of CryptoLocker due to the number of infections that occurred in various countries. Its main characteristics include encryption through 2048-bit RSA public key algorithms, the fact that it targets only certain types of file extensions, and the use of C&C communications through the anonymous Tor network.

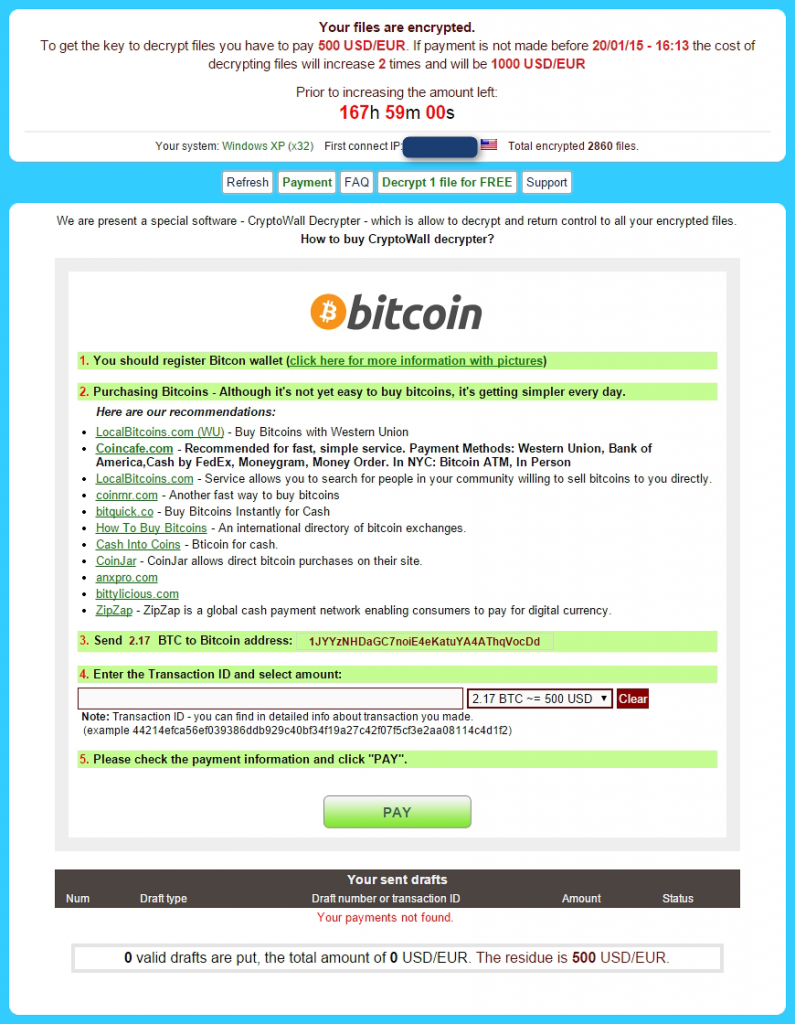

Almost simultaneously, CryptoWall (a variant of CryptoLocker) made its appearance and succeeded in outdoing its predecessor in terms of the number of infections, partly due to the attack vectors employed: from exploit kits in browsers and drive-by-download attacks to the most common method of sending malicious files as email attachments. This type of malware has adapted over time and evolved into a third version, with changes to various characteristics including its vectors of infection and payment methods.

Earlier this year, a new wave of ransomware was identified with the appearance of CTB-Locker, which can be downloaded onto the victim’s computer by means of a TrojanDownloader. Of the various versions in circulation, one was aimed at Spanish-speakers, featuring messages and instructions on making payments written in Spanish.

One of the features of this malware, also known as Critroni, is that it encrypts files on the hard disk, on removable drives and on network drives by using an irreversible elliptic curve algorithm. For the creator to maintain their anonymity, they connect to the C&C server via Tor and demand a ransom of eight bitcoins.

Ransomware has grown in diversity too

We have borne witness to how this type of threat has increased in scale, with increasingly complex mechanisms that make it almost impossible to get back the information without having to make a payment to the cybercriminal. Even then, that is no guarantee that the files will be recoverable.

Similarly, the threat has increased in terms of diversity too. For example, in 2014, we saw the first case of filecoder malware for Android, which is currently the most widespread platform for mobile devices. SimpLocker appeared on the scene displaying the same messages that were used for the police virus. It worked by scanning the device’s SD card for files with specific extensions for the same purpose: to encrypt them and then demand a ransom payment in exchange for decrypting them.

Other similar malware like AndroidLocker has appeared too. Its main characteristics include impersonating legitimate security solutions and applications for Android, in order to try and gain a user’s trust.

Continuing the process of diversification, in recent months there has been a significant increase in the use of ransomware targeting the Internet of Things (IoT). Various devices such as smart watches and TVs are susceptible to being affected by this type of malicious software, mainly those running the Android operating system.

Is this a threat that’s here to stay?

It is clear that the proliferation of ransomware is a growing trend, and one that is highly likely to keep on growing, not least because it is now possible to buy it as a service. Ransomware as a Service (RaaS) has been discovered to be available through a tool called Tox, which enables people to create this type of malware automatically, without requiring technical knowledge.

Similarly, with the recent revelation that the first open-source ransomware (Hidden Tear) has been published, a new window of opportunity has been opened for developing this malware – and variants of it – leading to predictions of increasingly sophisticated malware being developed and deployed on a massive scale.

The facts and figures lead us to believe that we are facing a threat that will continue to exist for years to come, due primarily to the unlawful but substantial profit it represents for its creators and the number of devices and users susceptible to being affected.

For this reason, the most important thing is to keep following good practices, using security solutions against malware, and above all to use common sense in order to avoid becoming a victim, or at least to ensure that the consequences of becoming infected are minimal. Despite everything, although the threat is complex, diverse, and widespread, the methods of distribution and infection have not changed greatly.

For for further reading, check out: 11 things you can do to protect yourself against ransomware, including CryptoLocker