Before we begin, let's make one thing really clear.

The malware problem on Mac OS X is nothing like as bad as it is on Windows.

There are something like 200,000 new Windows malware variants being discovered each day. Malicious code activity in the Mac world is far less frenetic, but the fact is, malware does exist that can infect our iMacs or MacBooks.

And if your Apple computer is unlucky enough to fall victim you're not going to feel any better than your PC-owning friends who are struggling to remove a backdoor Trojan or a pernicious browser toolbar from their copy of Windows.

Also, it's worth bearing in mind that Mac malware is not a new phenomenon.

Also, it's worth bearing in mind that Mac malware is not a new phenomenon.

Malware for Apple devices actually predates the Macintosh *and* the PC, with the first example being the Elk Cloner worm written by Rich Skrenta, and designed to infect Apple II devices way back in 1982.

But threats on Apple II and Apple computers running Mac OS 9 and earlier aren't really relevant anymore to anyone aside from historians.

What modern Mac users care about are what malware threats exist for Mac OS X.

And, it turns out, that 2014 will see the tenth anniversary of Mac OS X malware. Here are some of the more notable examples of worms and Trojan horses that have been seen for the platform in the last ten years.

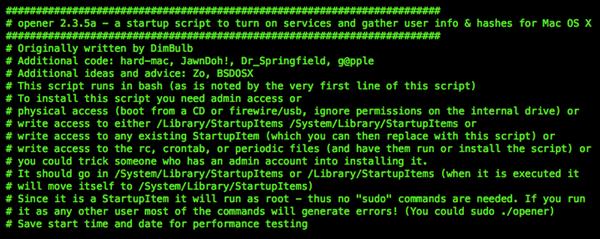

Renepo (2004)

As ESET's Mac malware facts webpage illustrates, the first malware specifically written for Mac OS X emerged in 2004.

Renepo (also known as "Opener") was a shell script worm, and contained an arsenal of backdoor and spyware functionality in order to allow snoopers to steal information from compromised computers, turn off updates, disable the computer's firewall, and crack passwords.

Renepo was never going to be a serious problem for the vast majority of Mac users, as it didn't travel over the internet and required the attacker to have access to your computer to install it. Nevertheless, it was an indicator that Apple Macs weren't somehow magically protected against malicious code.

Leap (2006)

Leap represented, for many people watching observing Apple security, the first real worm for the Mac OS X operating system.

Leap could spread to other Mac users by sending poisoned iChat instant messages - making it comparable to an email or instant messaging worm.

At the time, some Mac enthusiasts leapt (geddit?) to Apple's defence and argued that Leap "wasn't really a virus", but claimed it was a Trojan instead. But - in my opinion - they were wrong.

The argument typically went that because Leap required user interaction in order to infect a computer (the user had to manually open the malicious file sent to them via iChat), then it couldn't be a virus or a worm

But then commonly discovered examples of Windows malware encountered at the time either, like the MyDoom or Sobig, also required manual intervention (the user clicking on a file attachment). And yet, Mac users seemed very keen to call those examples of Windows malware "viruses" at every opportunity.

In my opinion, viruses is a superset consisting of other groups of malware, including internet worms, email worms, parasitic file viruses, companion viruses, boot sector viruses and so forth. Trojans are in an entirely different class of malware because – unlike viruses and worms – they cannot replicate themselves and cannot travel under their own steam.

Leap was rapidly followed by another piece of malware, a proof-of-concept worm called Inqtana which spread via a Bluetooth vulnerability.

So, next time someone tells you that there are no viruses for Mac OS X - you can now speak with authority and tell them, oh yes there are!

Jahlav (2007)

Things took a more serious turn with Jahlav (also known as RSPlug), a family of malware which deployed a trick commonly seen on Windows-based threats by changing an infected computer's DNS settings. There were many versions of Jahlav, which was often disguised as a fake video codec required to watch pornographic videos.

Of course, the criminals behind the attacks knew that such a disguise was a highly effective example of how social engineering could trick many people into giving an application permission to run on their computer.

The truth was that many Mac users, just like their Windows-loving counterparts, could easily let their guard down if they believed it would help them see X-rated content.

MacSweep (2008)

An early example of Mac OS X scareware, MacSweep would trick users into believing it was finding security and privacy issues on their computers - but in fact any alerts it displayed were designed simply to trick unsuspecting users into purchasing the full version of the software.

Snow Leopard (2009)

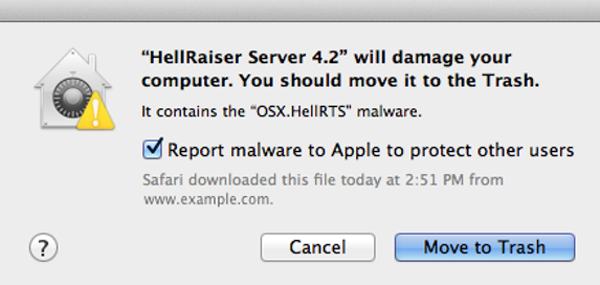

Snow Leopard isn't malware, of course. It was version 10.6 of Mac OS X, released in August 2009.

And the reason why it is included in this history of Mac OS X malware is because it was the first version of the operating system to include some built-in anti-virus protection (albeit of a very rudimentary nature).

Apple, rattled perhaps by the widespread headline-making infections caused by the likes of the Jahlav malware family, had decided it needed to do something.

However, as its anti-virus functionality only detected malware under certain situations (and initially only covered two malware families) it was clear that security-conscious Mac users might need something better.

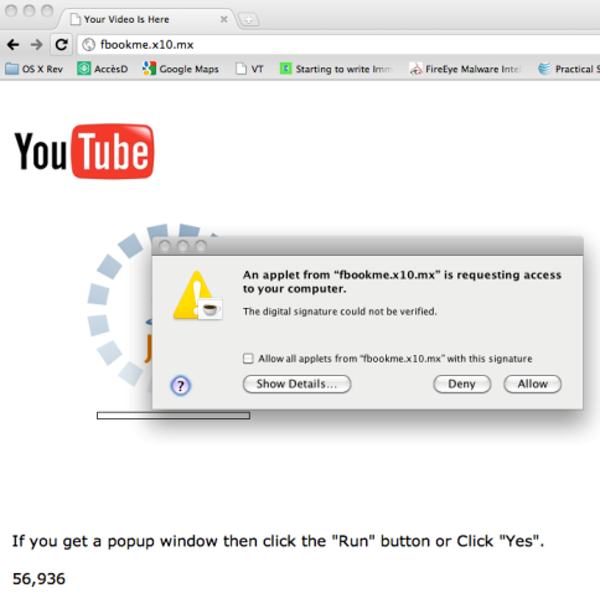

Boonana (2010)

This Java-based Trojan showed that multi-platform malware had well and truly arrived, attacking Macs, Linux and Windows systems.

The threat spread via messages on social networking sites. pretending to be a video and asking the enticing question "Is this you in this video?".

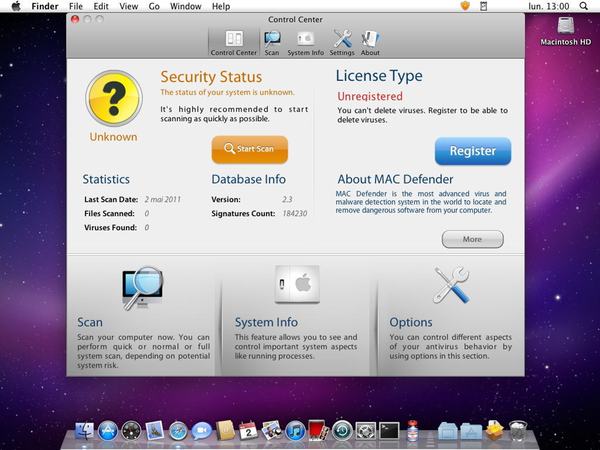

MacDefender (2011)

MacDefender saw Mac malware infections reach new heights, as many users began to report seeing bogus security warnings on their computer.

Using blackhat search engine optimisation techniques, malicious hackers managed to drive traffic to boobytrapped websites containing their rogue anti-virus scans, when users searched for particular images.

The danger, of course, was that users were being duped into handing over their credit cards in order to purchase a "solution" to the alarming messages.

Tens of thousands of people contacted Apple's technical support lines, requesting assistance.

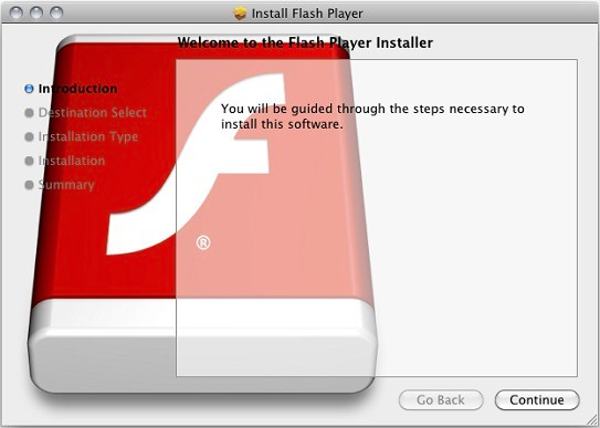

Flashback (2011/2012)

The Flashback malware outbreak of 2011/2012 was the most widespread attack seen on the Mac platform to date, hitting more than 600,000 Mac computers.

The attack posed as a bogus installer for Adobe Flash and exploited an unpatched vulnerability in Java, with the intention of stealing data (such as passwords and banking information) from compromised Mac computers, and redirecting search engine results to defraud users and direct them to other malicious content.

In September 2012, ESET researchers published a comprehensive technical analysis of the Flashback threat which is well worth a read, if you want to know more.

Lamadai, Kitm and Hackback (2013)

In recent years, Macs have also been used for espionage - and naturally suspicious fingers have begun to point towards intelligence agencies and government-backed hackers when very specific victims are targeted.

The Lamadai backdoor trojan, for instance, targeted Tibetan NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations), exploiting a Java vulnerability to drop further malware code onto infected users' computers,

Kitm and Hackback, meanwhile, spied on victims at the Oslo Freedom Forum, giving the malicious hacker the ability to remotely run commands at will.

LaoShu, Appetite and Coin Thief (2014)

So, what of 2014? Has the 10th anniversary been a notable year so far for Mac OS X malware?

Well, according to researchers at ESET, new Mac malware variants continue to be seen every week, putting Mac users who don't defend their computers at risk of data loss or having their computer compromised by an attack.

State-sponsored espionage continues to make its presence felt, with the discovery of Appetite, a Mac OS X Trojan that has been used in a number of targeted attacks against government departments, diplomatic offices, and corporations.

LaoShu meanwhile, has been widely spread via spam messages - posing as an undelivered parcel notification from FedEx, and scooping up documents of interest that have not been appropriately secured.

LaoShu meanwhile, has been widely spread via spam messages - posing as an undelivered parcel notification from FedEx, and scooping up documents of interest that have not been appropriately secured.

CoinThief, however, has probably received the most attention recently as it is distributed in cracked versions of Angry Birds, Pixelmator and other top apps, duping users into infection.

What made CoinThief most interesting, however, was that investigators found the malware was designed to to steal login credentials related to various Bitcoin-related exchanges and wallet sites via malicious browser add-ons.

In summary - protect yourself

This has just been a short history of Mac OS X malware. If you want to learn more about any of these threats, or are interested in any of the other Mac malware that ESET has seen in the last 10 years, be sure to check out the company's "Straight facts about Mac malware" webpage and consider taking the free trial of ESET Cybersecurity for Mac.

Because, even though there isn’t as much malware for Mac as there is for Windows, one infectious outbreak is too many, and we know that the bad guys are working hard to find fresh victims.