A little-known banking Trojan, developed in Russia, has managed to infect thousands of victims' computers without the knowledge of their owners.

Researchers at ESET say that they see several hundred infections of the Win32/Corkow banking Trojan every single day, but it has never seen the same attention from the security industry and media as its more infamous cousins such as Carberp.

All that is about to change, however, as ESET will be releasing a detailed technical examination of the Corkow Trojan next week, describing some of its more unusual features.

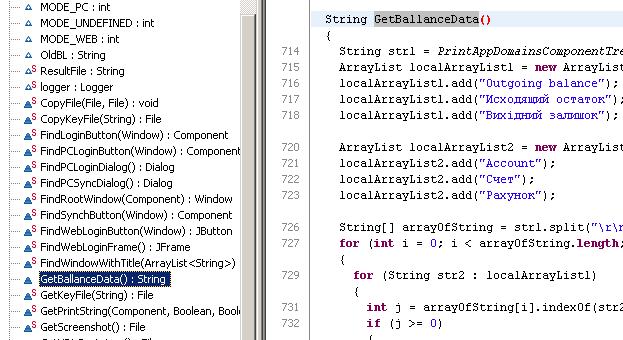

Like other advanced banking Trojans - such as Hesperbot which ESET researchers uncovered in September last year - Corkow is modular.

That means attackers can use different plug-ins to augment Corkow's capabilities.

These features include the standard fare: logging keystrokes to steal passwords, grabbing screenshots, web injection and form-grabbing to trick users into handing their personal information straight into the hands of the online criminals.

It's somewhat bemusing to see that there is no honour between thieves, as Corkow's routines for web injection and form-grabbing appears to be based on the leaked Zeus source code.

But beyond these familiar features for any banking Trojan, Corkow also contains modules that allow remote access by the hackers, and installation of the universal password stealer "Pony" (detected by ESET products as Win32/PSW.Fareit).

Corkow: Targeting Russian banking customers

Approximately 73% of Corkow infections seen by ESET come from Russia, with Ukraine responsible for 13% in second place.

It's perhaps unsurprising that these countries have been hit hardest, as Corkow contains a module to subvert the iBank2 banking system, used by a number of Russian banks and their corporate customers to facilitate speedy electronic banking and information exchange.

In addition, a separate Corkow module appears to target standalone banking applications from Sberbank, the largest bank in Russia and Eastern Europe.

Corkow: The malware with a taste for your browser history

A further module which can be deployed in Corkow deliberately collects a variety of information from several places on the infected computer - such as browser history, what applications you have installed and were last used, and a list of running processes.

What is interesting is that this information is then examined by the malware, which hunts for over 180 specific strings.

These mostly relate to various trading platform applications and websites, banking applications, and banking websites.

However, it's notable that Corkow also appears to be interested in websites and software related to the Bitcoin virtual currency, and computers belonging to Android developers who publish their apps on Google Play.

Quite what the criminals behind the Corkow malware plan to do by illegally accessing victims' Bitcoin accounts is probably obvious, but there are also sinister consequences if the login details of a legitimate Android developer were also to fall into the wrong hands.

Corkow: The malware that doesn't want to be analyzed

Hardly any money-making malware these days wants to find itself under the microscope of a security researcher. Many Trojans today will attempt to determine if they are being run in controlled, laboratory conditions and disguise their malicious nature by refusing to perform on demand.

Corkow does this in its own distinct way. Once installed, the malware's payload is encrypted using the Volume Serial Number of the C: drive, and behave innocuously if run on a separate computer from the one it initially infected.

This makes analysis, whether by a researcher or automated systems, more difficult, and may have resulted in some security firms failing to properly examine its malicious code in the past.

Corkow: The malware that slept

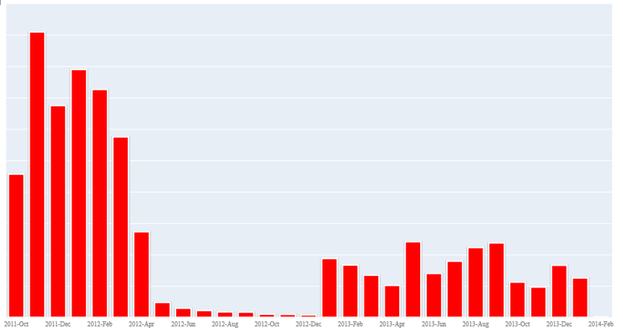

One of the more interesting aspects of the Corkow case is that it's the malware that slept. Although first seen in October 2011, attacks perpetrated by the malware more-or-less fell off the radar during 2012 only to see a sudden resurgence last year.

There's no clear explanation as to why the malware went effectively dormant for almost eight months - and that may be one mystery that is only adequately explained if the criminal gang behind Corkow are identified and brought to justice.

Researchers at ESET will publish more of their findings about the Corkow malware family in a technical paper to be published next week.

Meanwhile, computer users are advised to minimize the chances of infection by following safe computing best practices, keeping their anti-virus and security software updated, and ensure that patches are installed in a timely fashion.

Credit: Special thanks to ESET researcher Anton Cherepanov for his analysis of this malware.