In our previous blog, Filecoder: Holding your data to ransom, we published information about the resurgence of file-encrypting ransomware since July 2013. While the majority of these ransomware families are most widespread in Russia, there are families that are targeting users (especially business users) globally.

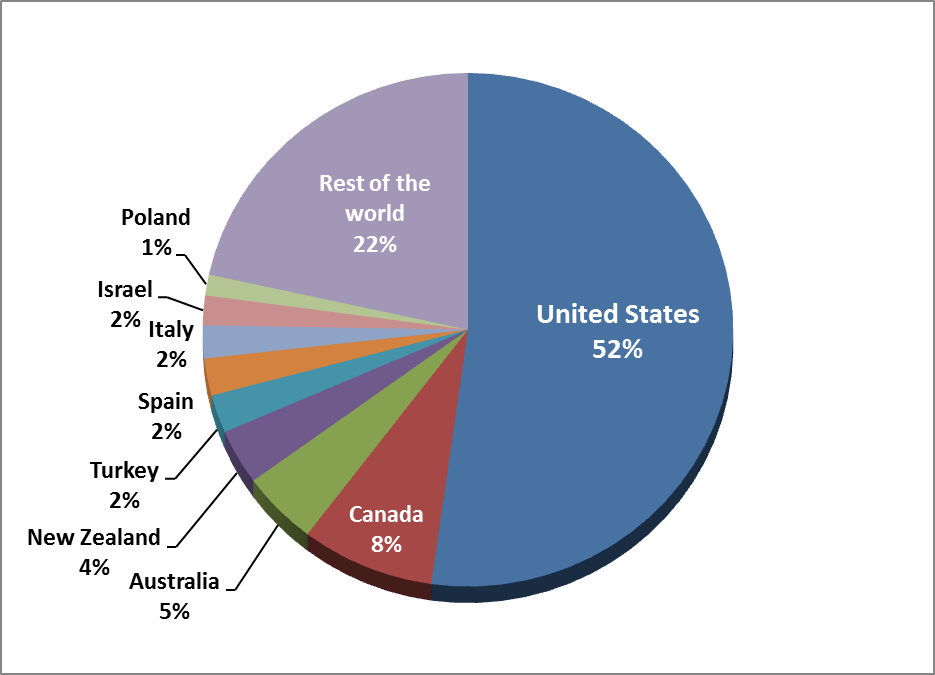

Cryptolocker, detected by ESET as Win32/Filecoder.BQ, is one of the most infamous examples and has received widespread public and media attention in the past two months. As shown by the ESET LiveGrid® detection statistics below, the country most affected by this family is the United States.

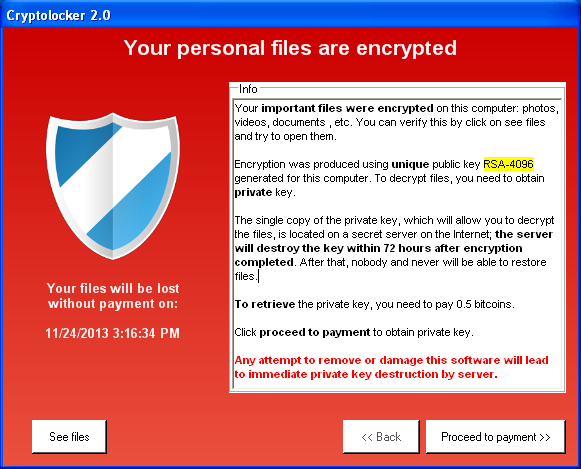

Last month we discovered another Filecoder family, which caught our attention because it called itself “Cryptolocker 2.0”. Naturally, we wondered if this is a newer version of the widespread ransomware developed by the same gang. In this blog post, we will provide a comparison between this “Cryptolocker 2.0” – detected by ESET products as MSIL/Filecoder.D and MSIL/Filecoder.E – and the “regular” Cryptolocker.

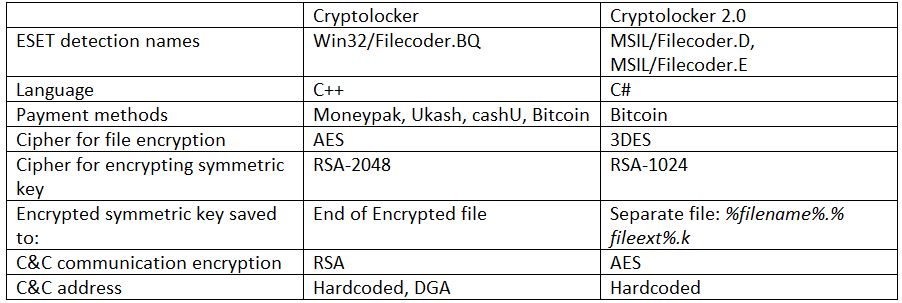

Cryptolocker 2.0 vs. Cryptolocker

Both malware families operate in a similar manner. After infection, they scan the victim’s folder structure for files matching a set of file extensions, encrypt them and display a message window that demands a ransom in order to decrypt the files. Both use RSA public-key cryptography. But there are some implementation differences between the two families.

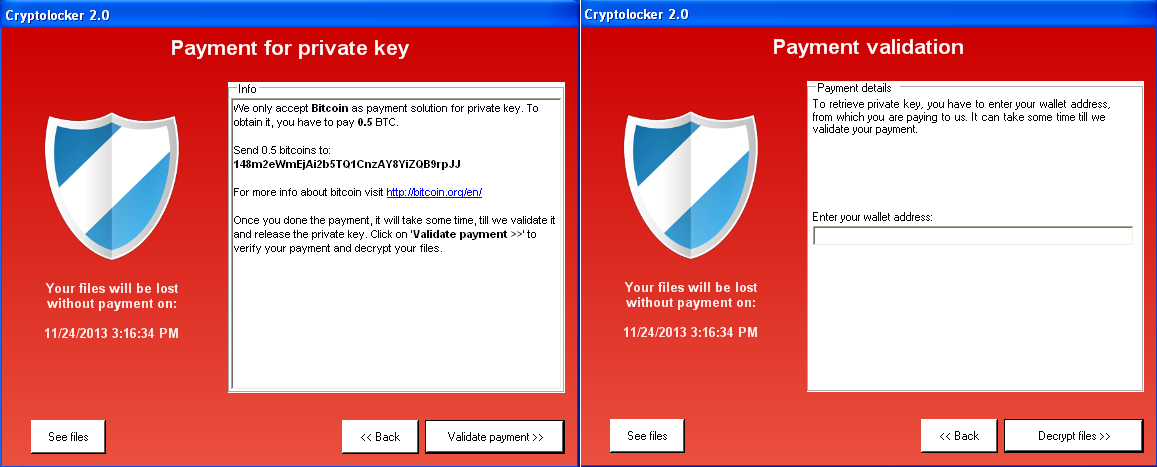

There are three visible differences between the two families. Cryptolocker uses (as mentioned in the ransom message) RSA-2048, whereas Cryptolocker 2.0 claims to use RSA-4096 (though in reality it uses RSA-1024). Cryptolocker 2.0 displays the deadline by which the private key will supposedly be deleted, but doesn’t show a countdown timer like Cryptolocker. And, interestingly, Cryptolocker 2.0 only accepts the ransom in Bitcoins, whereas different variants of Cryptolocker have also been accepting MoneyPak, Ukash or cashU vouchers.

More implementation differences were revealed after analyzing the malware. The first and most obvious difference is in the programming language used – Cryptolocker was compiled using Visual C++, whereas Cryptolocker 2.0 was written in C#. The files and Registry keys used by the malware are different, and, more interestingly, so is the list of file extensions that the ransomware seeks to encrypt. Cryptolocker appears to be more “business-user-oriented” and doesn’t encrypt image, video and music files, whereas Cryptolocker 2.0 does – its list of targets includes file extensions such as .mp3, .mp4, .jpg, .png, .avi, .mpg, and so on.

When the malware is run, it contacts the C&C server to request a unique RSA public key. Then, each file that meets specific criteria (matching file extension, file path not in exclusion list) is encrypted using a different randomly-generated 3DES key, and this key is then encrypted using the RSA public key received from the server. The encrypted key is then written to an auxiliary file, with the same filename and extension as the encrypted file and an appended second extension “.k”:

%filename%.%fileext%.k

Thus, decryption of the files would only be feasible if the RSA private key was known, which would allow the decryption of the 3DES keys.

The original Cryptolocker works in a similar fashion, with some subtle differences. For example, it uses AES instead of 3DES. Also, the encrypted key is saved to the end of each encrypted file, not in a separate file.

Cryptolocker (Win32/Filecoder.BQ) also contains a domain-generation-algorithm for C&C addresses, whereas the new Cryptolocker 2.0 doesn’t contain such a feature. An overview of the differences between the two malware families is presented in the table below.

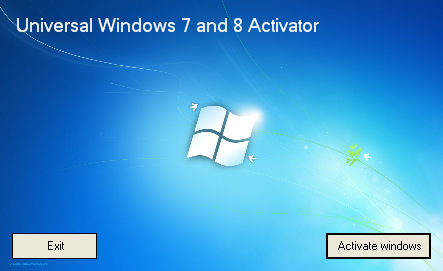

In addition to this, the recently-discovered trojan contains some features unrelated to the ransomware functionality. The application includes windows that mimic “activators” or cracks for proprietary software, including Microsoft Windows, Microsoft Office, Team Viewer, Adobe Photoshop or even ESET Smart Security.

The application chooses which window to display depending on the binary’s file name. After launch, it is installed on the system, and subsequently the malware operates in the “ransomware mode” as described above. This technique of masquerading as software cracks serves as an additional spreading mechanism for the trojan. Aside from the legal issues, this demonstrates the increased risks entailed when using pirated software.

Cryptolocker 2.0 is also capable of spreading via removable media by replacing the content of .exe files they contain with its own body.

The list of functionalities present in the trojan code is quite extensive and also includes stealing Bitcoin wallet files, launching the legitimate BFGMiner application or running DDoS attacks against a specified server. However, we were unable to establish whether this functionality was actually being used at present.

Conclusion

Taking into account all the aforementioned differences, it is unlikely that the malware that calls itself “Cryptolocker 2.0” is actually a new version of the previous Cryptolocker ransomware from the same authors. The switch from C++ to C# would be something unexpected to say the least, and in any case none of the key differences can be considered significant ‘improvements’.

More probably, someone used Cryptolocker as an inspiration for garnering some illicit earnings. After all, this is not the first copy-cat.

Nevertheless, the ransomware detected as MSIL/Filecoder.D or MSIL/Filecoder.E can still be a cause of distress to the victim, if they don’t have backups of their files. For this reason, the importance of a proper backup routine can never be emphasised enough.

Additionally, we recommend that our users update to version 7 of our security products (ESET Smart Security and ESET NOD32 Antivirus) so as to make use of the Advanced Memory Scanner feature, which has been proven to improve detection of new incarnations of malware variants, including ransomware.