Introduction

A new banking Trojan has been making its round in the past few months. First publicly discussed by LEXSI, this banking Trojan has been very active, infecting users throughout the world. Its modus operandi is banking fraud through web injection. While this approach has been present for a long time in various banking Trojan families, it is still effective. Win32/Qadars uses a wide variety of webinjects, some with Android mobile components, used to bypass online banking security and to gain access to user’s bank account. Usually, banking Trojans either target a broad array of financial institutions or focus on a much smaller subset, usually institutions of which the user base is geographically close. Win32/Qadars fall in the second category: it pinpoints users in specific regions and uses webinject configuration files tailored to the banks most commonly used by the victims. As we have been monitoring its evolution, we have seen six main countries affected by Win32/Qadars:

-

Netherlands

-

France

-

Canada

-

India

-

Australia

-

Italy

While most of the attacks directed to users in these countries were launched in waves, users in the Netherlands were targeted throughout the monitoring period. This threat caught our attention because:

-

It is still very active after six months and is continuously updated

-

It targets very specific regions of the world

-

It uses a wide range of webinjects, some of which were also used by another banking Trojan family in a completely unrelated campaign

-

It uses Android/Perkele to bypass mobile based two-factor authentication systems

Historical Perspective

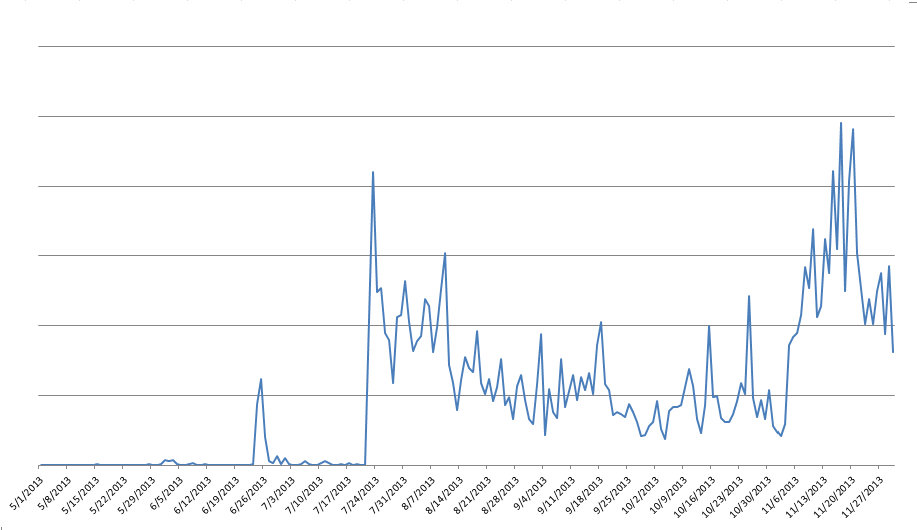

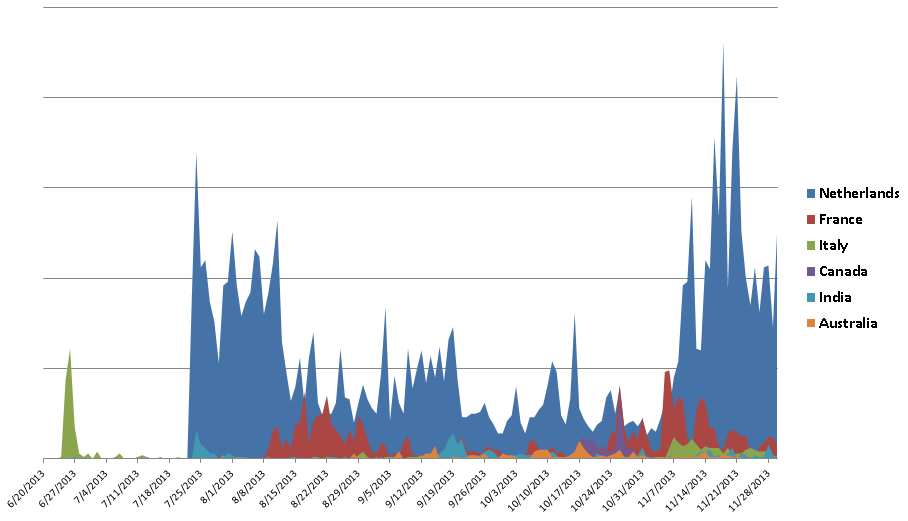

The first sign we saw of this malware was in mid-May 2013. The following graph shows the daily detection for Win32/Qadars.

Although the first detections occurred in May, the first true wave of infections occurred in late June. Interestingly, the authors seem to have been through a testing phase since the next detection spike was seen weeks later with barely any detections in between. Also, Italian users were mainly targeted in the first wave while the subsequent campaign mainly targeted Dutch users. We believe that this kit is either kept private or being sold only to selected people. We have seen a handful of different campaigns, but most of the infections we’ve analyzed are from the same campaign and thus share the same command and control (C&C) servers.

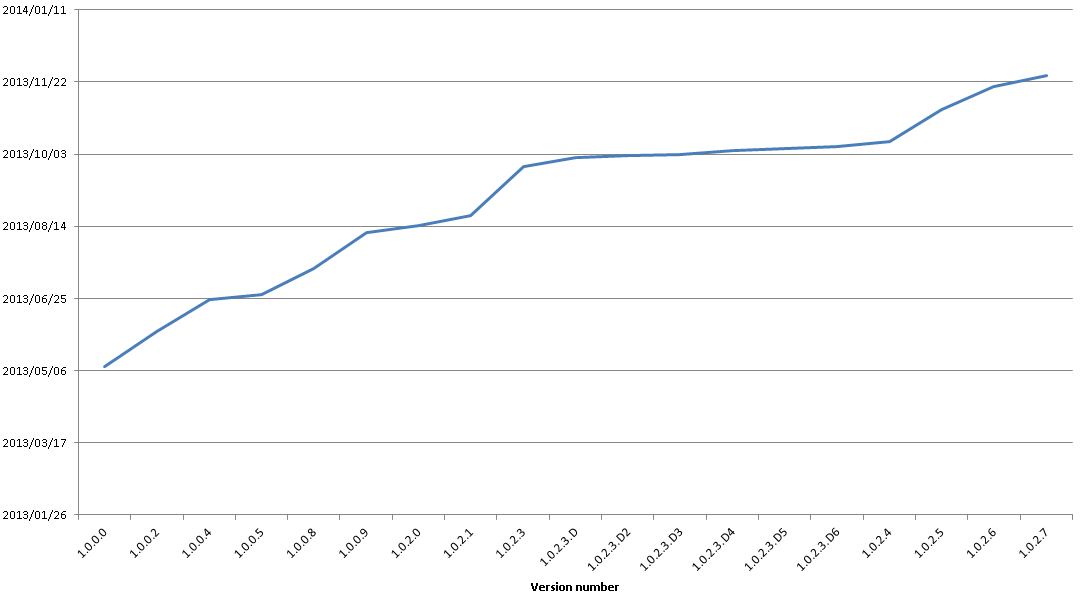

We can track the evolution of the malware through the build number that is embedded in the executable. The first version we saw was 1.0.0.0 and the latest one is 1.0.2.7. The steady release of new versions indicates that this malware is in constant maintenance and development. The following graphs shows the date each version was first seen by our telemetry data.

Technical Analysis

Win32/Qadars uses a Man-in-the-Browser (MitB) scheme to perform financial fraud. Just like Win32/Spy.Zbot, Win32/Qadars injects itself into browser processes to hook selected APIs. Using these hooks, it is able to inject content into pages viewed by the user. This injected content can be anything, but is usually a form intended to harvest user credentials or JavaScript designed to attempt automatic money transfers without the user’s knowledge or consent. Webinject configuration files are downloaded from the C&C server and contain the URL for the target webpage, the content that should be injected into the webpage and finally where it should be injected. This configuration file format is very similar to all the other banking Trojans out there. Once downloaded, the configuration is kept AES-encrypted in the computer’s registry keys. Currently, Win32/Qadars is able to hook two different browsers so as to perform content injection: Firefox and Internet Explorer. There is some stub for Chrome in the code, so we might see support for this browser in the future.

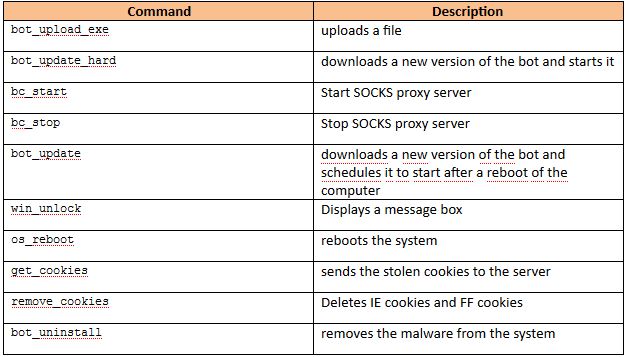

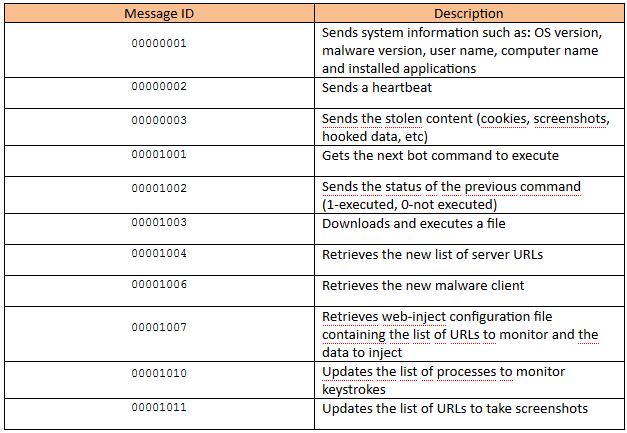

Once the malware is installed on a machine, the bot herder can control his bots through different commands, most of which are listed in the table below.

One addition that was made in version 1.0.2.7 is an FTP credential stealer. It supports a wide array of FTP clients and tries to open up their configuration files and steal the user’s credentials. Interestingly, in order to steal user credentials, it integrates some known static passwords that some of these FTP clients use by default to encrypt their configuration file. This behavior is not new and has already been seen in Win32/PSW.Fareit (Pony Loader), for example.

Network Communications

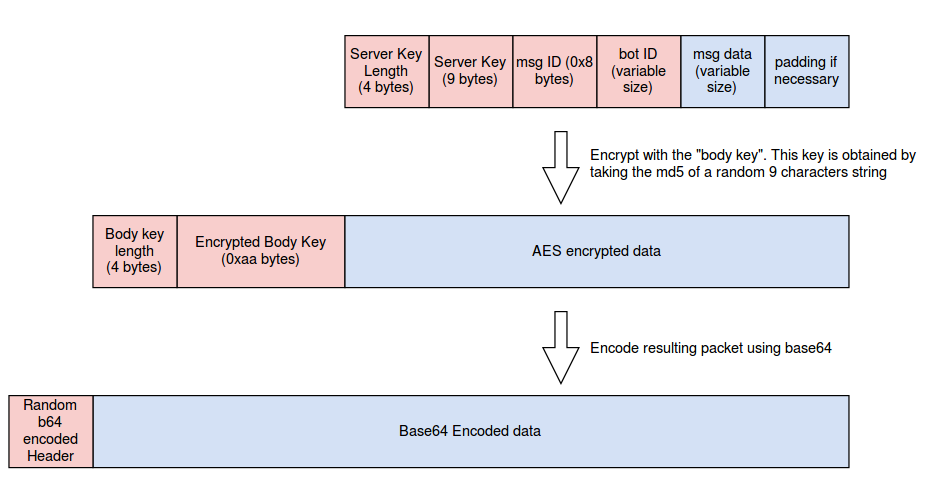

Win32/Qadars uses AES in ECB mode to encrypt its network communications. Before sending a message, the client will generate a random string of nine (9) characters and will use its MD5 hash as the AES key to encrypt it. It will also generate another random string which it will embed in the message sent to the server. This key will be used by the server to encrypt its response. To securely transfer the AES key used to encrypt the message to the server, the client will further encrypt it, two characters at a time, and append it to the message. Finally, the overall message is encoded using base64 and sent to the server. The following figure depicts this process and lists the different fields present in the messages sent to the server.

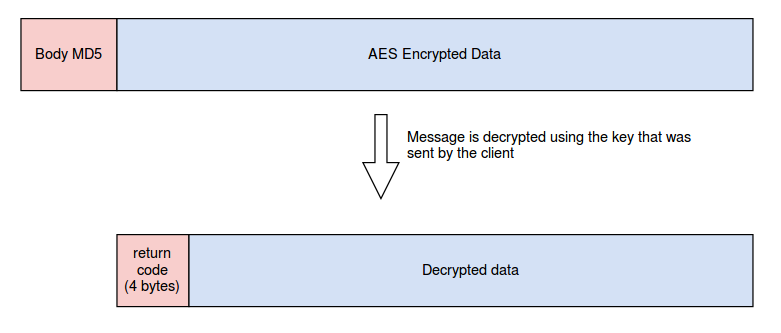

The server response is encrypted using the server key embedded in the client request. It also appends the MD5 digest of the message as an error detection mechanism. The following figure shows the structure of the server response.

Examining the different message IDs used by Win32/Qadars tells us more about its functionalities. The table below lists most of the different message IDs and their description.

Knowing the network protocol used by Win32/Qadars greatly enhanced our ability to track the botnet and study its behavior.

Infection Vector

Win32/Qadars' webinject configuration file changes frequently and targets specific institutions. To maximize their success with these webinjects, the malware authors try to infect users in specific regions of the world. In the following section, we will show which countries were the most targeted, but let’s first take a look at the infection vectors the malware author chose so as to target specific countries. From May to October, it is not clear how the malware was spreading. Through our telemetry system, we found several hints that they might have bought compromised hosts in the countries they were interested in. We draw this conclusion because all of the compromised computers we analyzed also had Trojan downloaders and other infamous Pay-per-Install (PPI) malware such as Win32/Virut.

Beginning in November, we saw that Win32/Qadars is now also being distributed through the Nuclear Exploit Kit. Below are a couple of URLs that were used to distribute it at the beginning of November. The Nuclear Exploit Kit pattern used at the time is clearly visible:

hxxp://nb7wazsx[.]briefthink[.]biz:34412/f/1383738240/3447064450/5

hxxp://o3xzf[.]checkimagine[.]biz:34412/f/1383770160/1055461891/2

hxxp://pfsb77j2[.]examinevisionary[.]biz:34412/f/1383780180/1659253748/5

Both of these infection vectors allow the bot masters to choose where the computers they compromise are located.

Regional Targets

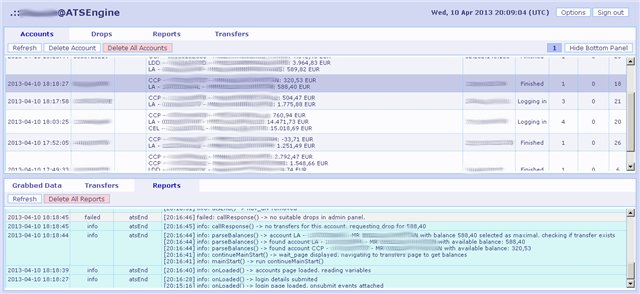

Win32/Qadars has focused mainly on six countries up until now: the Netherlands, France, Canada, Australia, India and Italy. The following graph shows the geographical distribution of the detection in the period May 2013 to November 2013.

Figure 5 : Detection Distribution

Win32/Qadars clearly seeks to infect Dutch computers as 75% of detections come from this region. Analysis of the times when it was detected show that there were several infection waves.

Detections in the Netherlands always show the highest prevalence, followed by detections reported in France. The case of Canada is particularly interesting as all of the detections in this country occurred in the last fifteen (15) days of October. Of course, the webinject configuration file downloaded by the bots at this time contains code that targeted the main Canadian financial institutions.

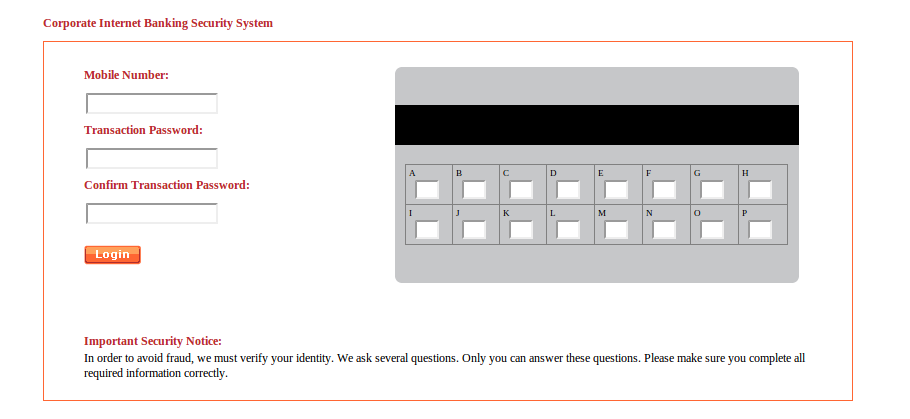

The webinject downloaded by the bots targets financial institutions in the 6 countries mentioned above with varying degree of sophistication. Some webinjects will just collect extra information whenever a user tries to login to his bank’s secure website. This is done through the injection of an extra form or elements asking the user for private information whenever he logs into his bank. An example form is shown below.

Other webinjects are much more complicated and can perform transactions automatically and bypass the two-factor authentication systems implemented by banks.

Webinjects

The webinjects used by banking Trojans can be obtained in several different ways. They can be directly coded by the cybercriminals who operate the botnet, or they can be bought. There are several coders offering to sell public webinjects or to produce them tailored to the customer’s wishes. There are many such offers and some will even ask for a different price depending on the features needed. When analyzing webinjects used by Win32/Qadars, it is clear that they were not all written by the same people as the techniques and coding styles are quite different. In fact, we believe that they were all bought on various underground forums. One webinject platform they use has a distinctive way of fetching external content such as scripts and images. The URL in the injected JavaScript will look something like this:

hxxp://domain.com/gate.php?data=cHJvamVjdD1tb2ItaW5nbmwtZmFuZCZhY3Rpb249ZmlsZSZpZD1jc3M=

The “data=” portion of the URL is base64 encoded. When decoded, this string reads “project=mob-ingnl-fand&action=file&id=css”, which clearly gives away the target as well as which file it is trying to retrieve. Interestingly, we found the exact same kind of syntax in webinjects used by a campaign targeting Czech banks and using Win32/Yebot (alias Tilon) as the banking Trojan. Although we found no trace of this particular webinject platform in the underground forums we looked at, we did find several other offerings.

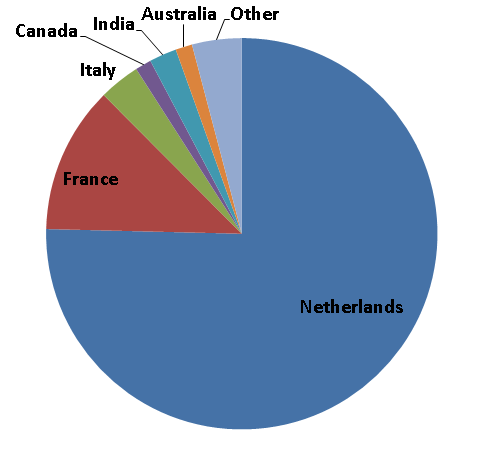

Automatic Transfer System (ATS)

ATS, now commonly used in banking Trojans, is a term applied to webinjects that aim to initiate an automatic transfer once a user accesses his bank account through a compromised computer. It will usually contain code to automatically find the account with the highest amount and initiate a transfer to an attacker/money mule controlled account. The code will usually contain some tricks (read social engineering) to defeat two-factor authentication systems that are sometimes imposed by banks when performing transfers. We have found several coders in underground forums selling public or private ATS for several banks around the world. In the underground forums, a “public” webinject is one that is sold to anyone by the vendor while a “private” one is customized to the buyer’s need and is usually not resold by the coder. In general, buyers of private webinjects will get the source code and the rights to redistribute it to others. We know that Win32/Qadars authors are buying some webinjects because we found one public ATS that they had integrated into their webinject configuration file. Like many other offerings, this coder sells, along with the webinject, an administrator panel (shown below) to let the cyber criminals control several aspects of how the automatic transfer should be carried out.

This particular offering is targeting a French bank and the coder claims that it can bypass the SMS two-factor authentication system put in place by the bank to prevent fraudulent transfers.

Perkele

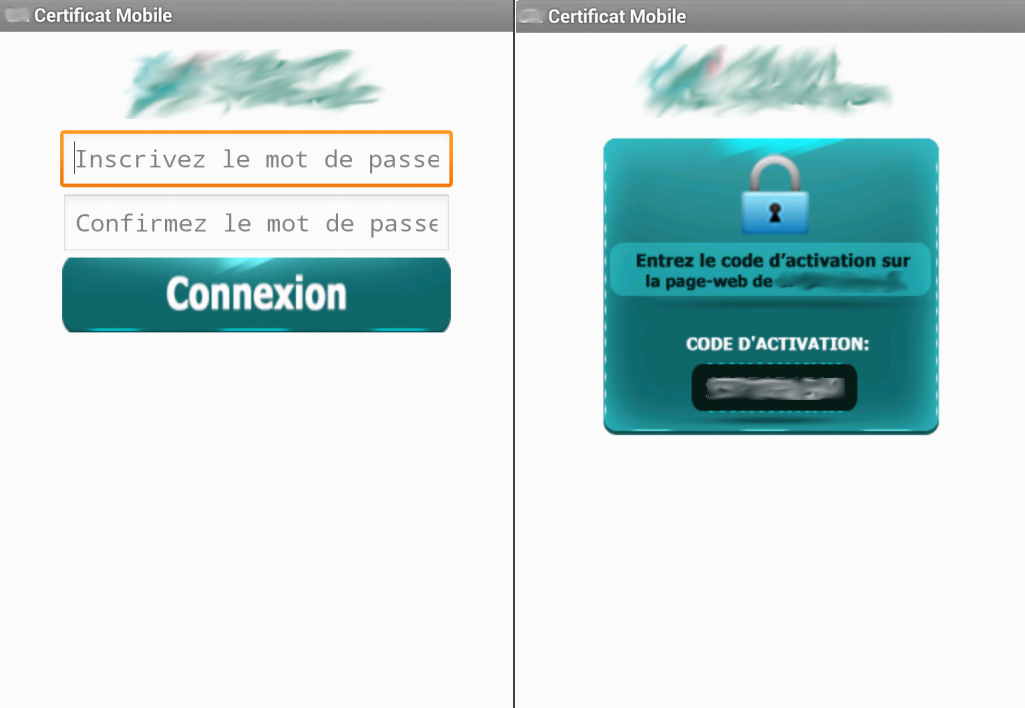

In several ATS we have analyzed, like the one described above, the malware must intercept an SMS so to make the transfer go through. This is necessary because the bank sends a transaction authorization number (TAN) to the user’s mobile whenever he initiates a money transfer. The user must input this TAN in his browser before the transfer is authorized. The usage of a mobile component by a banking Trojan is not new. Zeus-in-the-mobile, or ZitMo, and others have been around for quite some time. What is particularly interesting in this case is that several webinject coders are actually bundling such mobile malware with their webinjects. This means that a bot master can now buy very complex webinjects that are not only JavaScript code, but also contain an administration panel and some mobile malware customized to the targeted bank.

In the case of Win32/Qadars, the mobile component we’ve seen bundled with the webinject is Android/Perkele, mobile malware that can intercept SMS messages and forward them to the cybercriminals. This kit has already been profiled by Brian Krebs. The webinject takes care of everything in this case: when the user logs into his bank account, content is injected into his browser asking him to specify his mobile brand and to download a “security” application onto his mobile phone. Since the user sees this content while he is accessing his account, he is more likely to believe that this message is genuine and that the application truly comes from his bank. In one sample we analyzed, once the banking application is installed on the phone, it sends an SMS message to a phone number in the Ukraine.

Figure 9 : Screenshot of Android/Perkele Targeting a French Banking Institution

Android/Perkele supports the Android, Blackberry and Symbian operating systems, but we have seen only the Android component used in conjunction with Win32/Qadars. Once the application is installed on the user’s phone, the automatic transfer can be attempted, since the SMS containing the required TAN can be obtained by the fraudster. This webinject offering is a good example of malware commoditization. The botnet master can now buy a complete solution that will allow him to conduct automatic transfers and bypass two-factor authentication systems in a totally automated fashion. All he needs to provide is a way to inject content into the user’s browser. This functionality is implemented in all modern banking Trojans.

The mobile malware Android/Perkele, once installed on a user mobile, is used by fraudster to intercept SMS messages and hide them from the user. It is interesting to see that Google is taking a proactive stance in order to defeat this kind of threat. The newest Android OS, dubbed KitKat, has changed how the applications on the phone can receive SMS messages and hide them from the user. It will now be much more complicated to hide SMS because there is only one application that will be able to do that, and by default that is the system messaging application. Thus, users infected by threats like Android/Perkele will have a much better chance of spotting the infection if they are running the latest android OS.

Conclusion

We have seen lately a resurgence of new banking Trojans being spread in the wild. Win32/Napolar, Win32/Hesperbot and Win32/Qadars have all appeared in the last few months. It is probably no coincidence that there is now a plethora of banking Trojan source code available following the leaks of Win32/Zbot and Win32/Carberp source code. Another interesting development to watch for is the thriving webinject coder scene. These people are offering ever more sophisticated pieces of code that can bypass a wide range of two-factor authentication systems. It will be interesting to see whether at some point the market matures enough for us to see the emergence of popular webinject kits, in much the same way as happened in the exploit kit scene.

Special thanks to Hugo Magalhães for his contribution to this analysis.

SHA1 hashes

Win32/Qadars (Nuclear Pack): F31BF806920C97D9CA8418C9893052754DF2EB4D

Win32/Qadars (1.0.2.3): DAC7065529E59AE6FC366E23C470435B0FA6EBBE

Android/Perkele: B2C70CA7112D3FD3E0A88D2D38647318E68f836F