[Update: Norman released a comprehensive white paper profiling the group behind these attacks]

In the past few months, we have analyzed a targeted campaign that tries to steal sensitive information from different organizations throughout the world, but particularly in Pakistan. During the course of our investigations we uncovered several leads that indicate this threat has its origin in India and has been going on for at least two years. The journey began with a code-signing certificate and an exploit and the scope of the investigation has widened ever since. In this blog post, we will highlight several interesting artifacts of the campaign, but more will be revealed in my upcoming presentation at the 7th International CARO Workshop in mid-May.

Code signing certificate

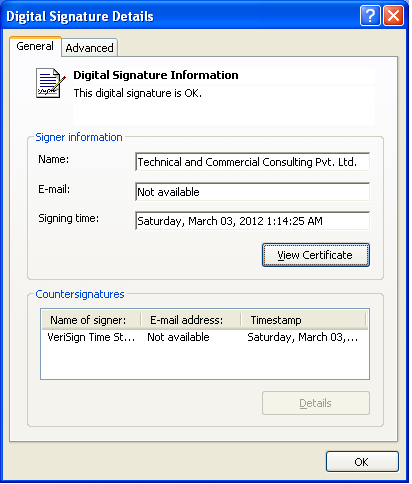

For part of this campaign a code signing certificate was used to sign malicious binaries and improve their potential to spread. This certificate was issued in late 2011 to an Indian company called Technical and Commercial Consulting Pvt. Ltd., based in New Delhi.

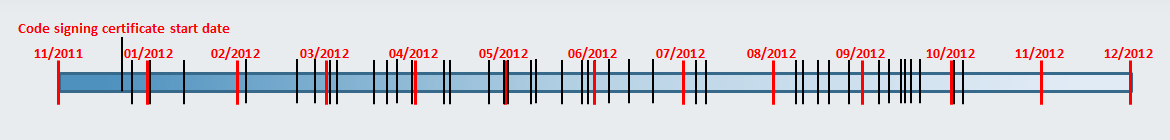

When we started our investigation, the certificate had been revoked for files signed after March 31st 2012. We contacted VeriSign with evidence that this certificate had been used maliciously since it was issued and they promptly revoked the certificate unconditionally. Overall, we found more than 70 signed malicious binaries using this certificate. Since each signed sample comes with an authoritative timestamp, it is possible to draw a timeline depicting when these binaries were produced:

Figure 1 Timeline of signing times. Black lines represent one sample signing time

From the information we gathered, the attackers were actively signing malicious binaries from March until June 2012. Then, there is a gap in the timeline, from the beginning of July until the beginning of August 2012. We then see another spike in certificate usage (even though it had already been revoked) in August and September 2012. There are several possible explanations as to why there is a gap during the summer of 2012, but it is likely that this was the off-season for both the attackers and their targets.

Although the investigation started with this code signing certificate, we then discovered several similar unsigned samples that were used in this campaign. Some of them were collected as far back as early 2011.

Droppers and decoy documents

The first infection vector we saw was using the famous CVE-2012-0158 vulnerability. This vulnerability can be exploited by a specially crafted Microsoft Office documents and allows arbitrary code execution. In the case we analyzed, a two-stage shellcode is executed when the user opens an RTF document. First, the shellcode sends information about the system to the domain feds.comule.com and then downloads a malicious binary from digitalapp.org.

The other infection vector we found used PE files disguised as Microsoft Word or PDF documents, most likely distributed through email. When the user executes the file, the malicious program downloads and executes additional malicious binaries (more on these executables below). To evade suspicion by the victim, a decoy Word document is shown to the user. We have identified several different documents that followed different themes.

One of these themes is the Indian armed forces. We do not have inside information as to which individuals or organizations were really targeted by these files. However, based on our detection metrics, it is our assumption that people and institutions in Pakistan were targeted.

The text in this first document seems to be a collage of various sources. The fake PDF document was delivered through a self-extracting archive called “pakistandefencetoindiantopmiltrysecreat.exe”:

This other PDF document was delivered through an executable called “pakterrisiomforindian.exe”:

In this case, the text comes from the Asian Defence blog, a blog aggregating Asian military news. Our telemetry data shows that this file was first seen in August 2011 on a system in Pakistan.

Payloads

We found many different types of payloads installed by the droppers, all of them were geared towards exfiltrating data from an infected computer to the attackers’ servers. The following table groups the binaries in different families and details their general characteristics.

| Category | Description |

| Downloader | Downloads executables from C&C and executes them. |

| Document uploader | Searches and uploads documents (csv, pdf, doc, docx, xlsx, etc) found in the trash and in the “My Documents” folder. |

| System information gathering | Sends information about the infected system to the C&C using GET requests. It uses WMI to gather information on the infected system such as: Antivirus installed on machine; OS version; Presence of files to upload |

| Keylogger | Records keystrokes and sends log to attacker server using POST requests. |

| Screenshot | Takes a screenshot of the desktop and sends it to the C&C. |

| Connect-back shell | Continually tries to connect back to an hardcoded IP address and allows the attacker to open a remote command shell. |

| Public Tools | We found two public tools (WebPassView and Mail PassView) from NirSoft and signed by the malicious certificate. These legitimate tools can be used to recover passwords used in email clients or stored in browsers. |

| Self-replication through removable drives | Monitors removable drive insertion events and copies different malware files to the inserted drive. It tries to lure the user into executing one of the copied files by renaming it with an existing folder name and hiding the latter. |

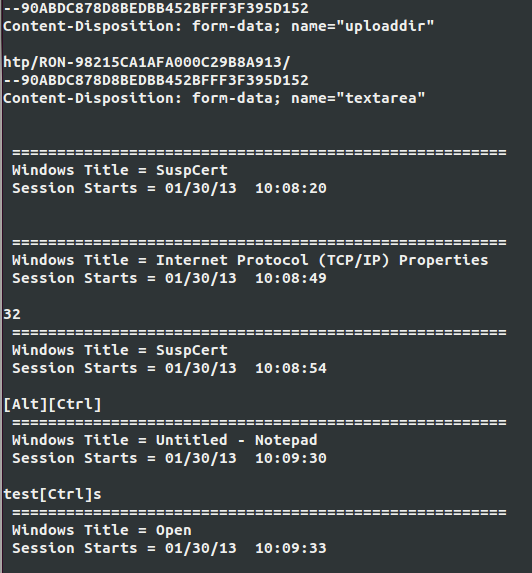

The information stolen from an infected computer is uploaded to the attacker’s server unencrypted. The decision not to use encryption is puzzling considering that adding basic encryption would be easy and provide additional stealth to the operation. The screenshot below shows a typical keylogger log:

The logs are very verbose and display the active window, the characters typed and the special keys in brackets. Since these logs are sent unencrypted, it is easy to detect the presence of an infected machine on your network by examining your HTTP network traffic.

In terms of persistence, many binaries we have analyzed add an entry in the Windows startup menu with a deceptive name. The screen shot below shows an example of such a startup menu:

While this technique allows the different components of the attack to be launched after each system reboot, it cannot be labelled as stealthy. Since targeted attacks usually try to stay under the radar as long as possible, we were surprised to see this technique used in this case.

C&C infrastructure

Most of the analyzed binaries contain a URL from which additional components are downloaded or to which an infected system’s content is uploaded. Sometimes, the C&C URL appears unencrypted in the binary. Other times, it is trivially encoded using a simple one-character rotation (ROT-1) as depicted below:

“gjmftbttpdjbuf/ofu” encrypted to “filesassociate.net”

We uncovered more than 20 domains linked to this campaign. While some still had an active DNS record, most of them did not resolve to an IP address. Using historical data around these domains, we were able to discover where these sites were hosted. It turns out that almost a third of all domains were hosted by OVH. This web hosting service has a reputation for hosting malware and spam content. In a recent HOSTExploit report it was ranked number 5 in the top 50 hosts for concentration of malicious activity served from an Autonomous System.

Most of the domain names are very close to real site or company names. This is a common tactic to try to conceal the true purpose of the C&C server. Two examples are “wearwellgarments.eu” and “secuina.com”. The former is very close to a real website called “wearwellgarments.com” while the latter looks like a misspelling of information security firm Secunia.

Origins of the malicious files

Analyzing this campaign allowed us to identify a few key indicators pointing to the geographic origin of these malicious files. We believe they all come from India. First, the code signing certificate was issued to an Indian company. In addition, all the signing timestamps are between 5:06 and 13:45 UTC, which is consistent with 8-hour work shifts falling between 10:36 and 19:15 in Indian Standard Time. This might seem a bit late, but considering that signing the binary is the last step in the development effort, it is likely that the malware authors were living in this time zone.

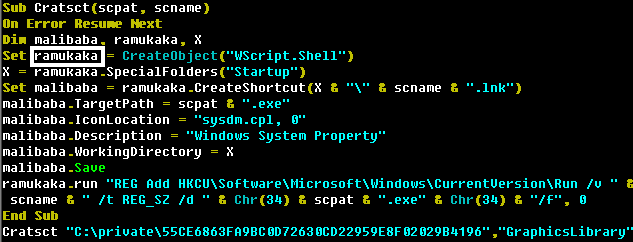

We also found several strings in the binaries that are related to Indian culture. In several scripts, a variable called ramukaka is used:

Ramu Kaka is a typical Bollywood-style servant in a house. Considering that this variable is responsible for achieving persistence on the system, this definition is a good fit.

The most compelling argument is found in our telemetry data. We found that many malware variants tied to this campaign appeared in the same location over a very small period of time. Each variant had only minor differences from each other, strongly suggesting an attempt by a malware creator to evade detection by our product. These files all appeared in the same region of India.

Infection statistics

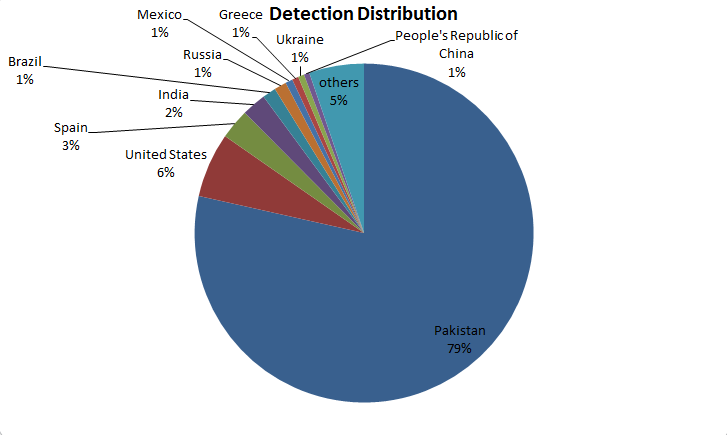

Our telemetry data shows that Pakistan is heavily affected by this campaign. The following graph shows the detection distribution we have observed for all the malicious files we linked to this campaign in the last two years.

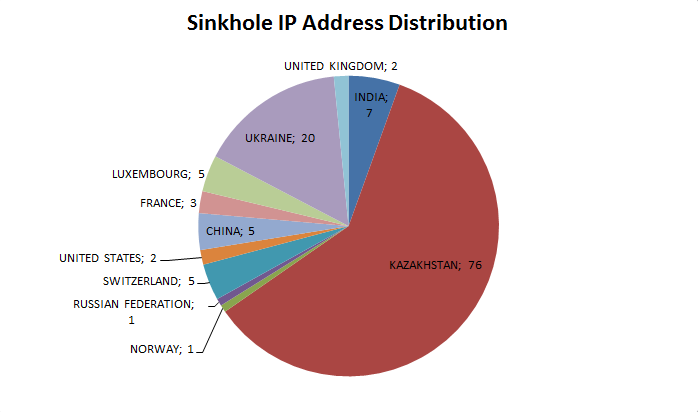

Thanks to our sinkholing of three domain names used by this campaign, we were also able to gather statistics on the geographical location of infected hosts.

Thanks to our sinkholing of three domain names used by this campaign, we were also able to gather statistics on the geographical location of infected hosts.

As one can see, the regional distribution presented in the last two graphs is very different. Ukraine and Kazakhstan account for three quarters of all IP addresses seen during the sinkholing operation. This difference can be explained by the possibility that unique domains are only for specific sub-operation in this campaign. If that was the case, the sinkhole data we are seeing would only be a very partial view of the whole campaign.

As one can see, the regional distribution presented in the last two graphs is very different. Ukraine and Kazakhstan account for three quarters of all IP addresses seen during the sinkholing operation. This difference can be explained by the possibility that unique domains are only for specific sub-operation in this campaign. If that was the case, the sinkhole data we are seeing would only be a very partial view of the whole campaign.

Conclusion

This post examined evidence of a far-reaching targeted campaign aimed at different targets throughout the world. Our analysis indicates that the entire campaign originates from India. Although we have seen a number of infections throughout the world, it seems that the most prominent target is Pakistan. Targeted attacks are all too common these days, but this one is certainly noteworthy for its failure to employ advanced tools to conduct its campaigns. String obfuscation using simple rotation (a shift cipher), no cryptography used in network communication, persistence achieved through the startup menu and use of existing, publicly-available tools to gather information on infected systems shows that the attackers did not go to great lengths to cover their tracks. On the other hand, maybe they see no need to implement stealthier techniques because the simple ways still work.

SHA1 Hashes

CVE-2012-0158 RTF Document: 3b1d9d65159bea24ab1060e5603f9e3c2d38d08d

pakterrisiomforindian.exe: d859f1cf99049f89258c1faa59dcd97f587e45ac

pakistandefencetoindiantopmiltrysecreat.exe: 1db89237ef786c7f22a8d4cd7eccda8f6286a6de

Downloader: 08ce405f0a0277de355454862b164ffd94a7ea36

Document uploader: DB22E7DEA0C1CAF203072693485DE4E4FD2CB56A

System information gathering: 0D610F3F51750EADCF426E10E6DE5313605400FA

Keylogger: AE7B9CFB10CD65B98C59DC012D6726B66BE92897

Screenshot: A0DD0B8FD0C98E917BFDC96182088CAB5505CCD2

Connect-back shell: 09D4ECA67B1D071E57C5951D97FE9DD9C62F1580

Self-replication through removable drives: 20A29D1F89C07BAFBB4C61CE208531D68125C8EDetection Names

Below are ESET threat names related to this case:

Win32/Agent.NLD worm

Win32/Spy.Agent.NZD trojan

Win32/Spy.Agent.OBF trojan

Win32/Spy.Agent.OBV trojan

Win32/Spy.KeyLogger.NZL trojan

Win32/Spy.KeyLogger.NZN trojan

Win32/Spy.VB.NOF trojan

Win32/Spy.VB.NRP trojan

Win32/TrojanDownloader.Agent.RNT trojan

Win32/TrojanDownloader.Agent.RNV trojan

Win32/TrojanDownloader.Agent.RNW trojan

Win32/VB.NTC trojan

Win32/VB.NVM trojan

Win32/VB.NWB trojan

Win32/VB.QPK trojan

Win32/VB.QTV trojan

Win32/VB.QTY trojan

Win32/Spy.Agent.NVL trojan

Win32/Spy.Agent.OAZ trojan